Welcome music lovers to another edition of ‘Listening Sessions.’ Since the last time I was in touch, there have happily been a few new subscribers to my Substack. For those new to ‘Listening Sessions,’ thank you for subscribing! I am so pleased to have you here.

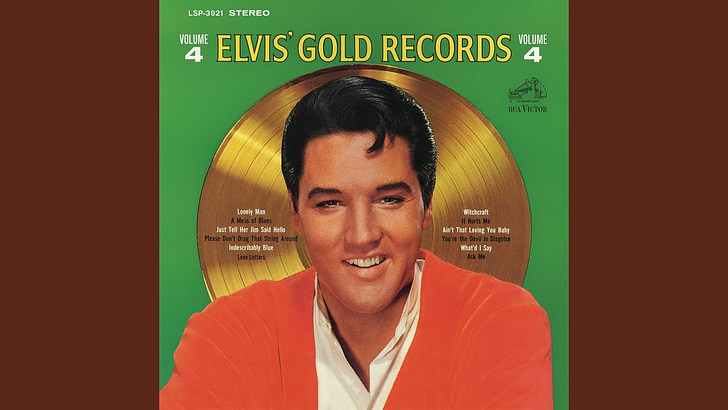

With Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis hitting theatres last month, there’s been renewed interest about Elvis Presley, his legacy and whether he continues to matter (this article offers some interesting thoughts on that topic).

The below essay only tangentially mentions the new Elvis biopic and instead, focuses on a series of recordings Elvis made in Nashville between May 1966 and January 1968. It was perhaps the most commercially fallow period of his career but amidst the diminishing returns of movies and movie soundtracks was a collection of recordings that stand as among Elvis’ most interesting and varied. Taken together, they provide a vantage point to better understand the comeback that started with the famous NBC special taped in June 1968 and aired on December 3 of that year. I hope you’ll enjoy reading the essay and check out some of the music mentioned. What are some of your favourite Elvis songs from this time period?

Stay tuned early in August for my next essay, a look at Ray Charles and the birth of Impulse! Records.

Until next time, may good listening be with you all.

If you’re reading this and are not yet a subscriber of ‘Listening Sessions,’ I hope you'll click the button below to subscribe and get each edition delivered straight to your inbox. I publish a long-form essay on music three times a month, every 10 days or so.

If you are a subscriber, share ‘Listening Sessions’ with any music fans in your orbit.

When Elvis Presley arrived at 10 p.m. at RCA’s Studio B in Nashville on May 25, 1966, it had been two years, four months and 13 days since he had been in a recording studio for any reason other than for his movies. The balancing act that had characterized his recording career in the early sixties between soundtrack and non-soundtrack records had been upset by the financially obvious yet artistically dubious fact that movie soundtracks were more commercially successful than LPs like Elvis is Back! So, the album that was to have resulted from two days of sessions in Nashville in May 1963 never materialized and after three songs were put on tape on January 12, 1964, all efforts to record anything not meant for the movies were abandoned.

Looking at Elvis’ singles released in 1964 and 1965, they reveal a confusing array of new and recycled music with the only bona fide hit, ‘Crying in the Chapel,’ recorded as part of the His Hand in Mine session on October 30, 1960. By the end of 1965, RCA had reached way back in the vaults to 1957 to exhume ‘Tell Me Why,’ which hung around the outer reaches of the Billboard Top 40. Moreover, the touting of Elvis for Everybody!, released in August 1965, as his first non-soundtrack album since 1962 was pure PR puffery for a collection of studio leftovers that in actuality included five movie songs.

While his albums remained top 10 sellers, the feeling that Elvis was slipping further and further into the quicksand of cultural irrelevancy was unmistakable. Yes, as always, his innate artistry and talent still managed to shine through from time to time (ballads like ‘Tender Feeling’ from Kissin’ Cousins and ‘Puppet on a String’ from Girl Happy come to mind as does a solid rocker like his cover of Leiber and Stoller’s ‘Little Egypt’ shoehorned onto the Roustabout album) but how can one look at the cover of the inexplicable Harum Scarum, in which Elvis looks utterly baffled at being dressed like an Ali Baba theme park extra, and not wonder what he was doing to his career. What was in the pipeline for 1966: Frankie and Johnny and Paradise, Hawaiian Style, foretold of darker days to come. At the dawn of that year, Elvis turned 31 but in a time where not trusting anyone over 30 was quickly becoming the credo of the American youth, he seemed older beyond his years.

The story we are usually told about Elvis is that it took the NBC special that was shot in June 1968 and premiered later that year on December 3 for him to reverse the backward momentum of his career and begin the renaissance that reached full bloom in 1969 and carried him into the beginning of the seventies.

The broad strokes of this story ring true, but the underlying assumption, that Elvis’ artistry had completely stalled and that he was making music of absolutely no substance ignores an important reality: that in the two years prior to the NBC special, in the midst of the movies and soundtrack albums, Elvis was reviving the artistic ambition that animated his early-sixties sessions in Nashville to create one of his most unique collections of music. Whereas the non-movie recordings from 1960 to the beginning of 1964 were an effort to create an Elvis of mass appeal, An Elvis for Everyone, the non-movie recordings he made in Nashville from May 1966 to January 1968 were ultimately less about commercial considerations and more about making records that engaged Elvis’ interests and reinvigorated his love of music and of making it. Here instead was An Elvis for Himself.

“I searched and I searched but I could not find”

“What are you into?” - Elvis to Larry Geller; March 30, 1964

Amidst the numbing parade of movies and the early signs of a career in crisis, Elvis was not entirely watching it unfold passively, it was just that he was engaged in a quest far removed from his aspiration to be a singer of dazzling versatility or an actor inheriting the mantle of Brando or Dean. It was ignited the day his regular hairdresser was unavailable and in his stead, a 24-year-old stylist by the name of Larry Geller was dispatched to the home Elvis was renting on Perugia Drive in Bel Air. After a wash, trim and style, Elvis posed a pointed question to Geller: “What are you into?” The answer Geller gave about his search for the spiritual meaning of life shook Elvis, because what Geller was describing was exactly what he was searching for too and before he let Geller go, Elvis convinced him to quit his job and work for him instead.

Geller became Elvis’ spiritual guru, bringing him books like The Impersonal Life and Autobiography of a Yogi and engaging in long, philosophical discussions with him to the chagrin of the other guys in Elvis’ orbit—the so-called Memphis Mafia—who were left on the outside looking in with confusion, jealousy and more than a little contempt. How much of this was the result of a genuine concern for Elvis as opposed to a selfish lament that an Elvis more interested in transcendental spiritual experiences—for a while, he even entertained the notion of quitting the music business to become a monk—than tackle football was not a whole lot of fun? I think it was probably a lot of the latter and at least a little bit of the former.

Colonel Tom Parker was also alarmed at the singer’s transformation as well as that his get-rich-quick strategy of gearing everything towards the movies was paying fewer and fewer dividends. With a new contract with RCA finalized in the fall of 1965, and the obligations it entailed gnawing at him, the Colonel slowly realized that the status quo had to go. Elvis had to get back in the studio.

The zeal that Elvis poured into exploring matters of the spirit spilled over into preparations to record in Nashville in May 1966. On the turntable were albums by Peter, Paul & Mary, Aretha Franklin, Ian & Sylvia, Odetta and others. Elvis would tape three-part harmonies with Charlie Hodge and Red West. There was an atmosphere of promise, especially as the agenda for the session was centered around recording a new gospel album. No music spoke more directly to Elvis. As he recounted to a reporter around this time, “I feel God and his goodness, and I believe I can express His love for us in music.”

“I memorized every line”

The group that was assembled in RCA’s Studio B awaiting Elvis’ arrival on May 25 was a mix of old and new faces. Stalwarts Scotty Moore on guitar and D.J. Fontana on drums were there as were charter A Team members Floyd Cramer on piano, Bob Moore on bass, Buddy Harman on drums and Boots Randolph on tenor saxophone. They were augmented by A Team up-and-comers Chip Young on guitar, Pete Drake on steel guitar and Charlie McCoy who could play just about everything (those who recall Ken Burns’ series on country music may remember a remarkable montage of hits that McCoy played on, each of them on a different instrument, including the memorable downward guitar riff on Bobby Bare’s ‘Detroit City’).

As if to explicitly emphasize the level of ambition Elvis was bringing, there were not only the Jordanaires: Gordon Stoker, Neal Matthews, Jr., Hoyt Hawkins and Ray Walker, as well as soprano Millie Kirkham on hand to sing backgrounds but also two additional female singers: June Page and Dolores Edgin, and a new Southern gospel supergroup.

The powerful and extroverted Jake Hess was among a handful of singers, Roy Hamilton, Bill Kenny of the Ink Spots, Clyde McPhatter as well as Dean Martin also come to mind, that were formative influences on Elvis’ tone, approach and phrasing. After leaving the Statesmen Quartet, perhaps the greatest exemplars of the Southern gospel style with harmonies that used the widest of intervals, liberal doses of bravado and a revival-tent fervor that took the dictum to “make a joyful noise unto the Lord” as literally as possible, Hess formed the Imperials. Joining him were pianist Henry Slaughter and bass singer Armond Morales, both from the Weatherford Quartet, baritone Gary McSpadden from the Oak Ridge Boys (long before ‘Elvira’) and tenor Sherrill Nielsen of the Speer Family. The choir would have been expanded to a 12th voice if Jimmy Jones, a Black gospel singer whose album What the Lord Has Done for Me was part of Elvis’ home listening of late, had been found and invited to join the sessions.

Another sign of the significance attached to the upcoming sessions would be the presence of a new producer behind the recording booth. Felton Jarvis had tried his hand at singing, promoting sheet music and engineering before getting a chance to do what had always been his goal: producing records. While at ABC-Paramount, he scored a chart-topper with Tommy Roe’s Buddy Holly-esque drenched ‘Sheila’ before moving to RCA in 1965. Chet Atkins, Elvis’ nominal and mostly indifferent producer, sensed Jarvis, possessing a gregarious and infectious personality, was a natural to take his place. That he was fairly sure that Elvis and Jarvis would quickly hit it off with each other (they most certainly did) was a bonus.

A less important, but still noteworthy, sign of the artistic fires burning renewed within Elvis was the February 1966 soundtrack session for Spinout. Sounding noticeably more engaged than he did for the mostly desultory music for Frankie and Johnny and Paradise, Hawaiian Style, Elvis laid down affecting performances of the ballads ‘All That I Am’ and ‘Am I Ready?’ as well as of the churning Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman number ‘Never Say Yes.’ The record-buying public wouldn’t, by virtue of Spinout being released in October, have any inkling of this. That would instead come but 11 days after the conclusion of what turned out to be four nights of recording in Nashville with the release of a new single, underscoring the urgency that RCA felt about getting new music out into the market.

The A side was ‘Love Letters,’ an old standard that R&B singer Ketty Lester revived in 1962 and took into the Billboard Top 10. It’s her version that provides the template for Elvis’. Built around a recurring, chiming piano part, played on Lester’s version by Lincoln Maygora, that fits so snugging with Victor Young’s melody and Edward Heyman’s lyrics, it’s Music City newcomer David Briggs who replicates it on Elvis’ recording. Briggs was called to Studio B on the second night of recording when Floyd Cramer was unavailable until later in the evening and who, once he arrived and the tape began to roll, provided a counterpart on organ to Briggs’ piano. Kirkham, Page and Edgin offer a lush background to Elvis’ vocal, which reflects a deep appreciation of the song as well as with Lester’s interpretation—hear how he stretches out “I read the name that you sign” in the repeat of the verse. The flip side, a cover of a Clyde McPhatter number ‘Come What May,’ is less serious-minded and more full of bonhomie.

The single fared well, hitting #19 on the Billboard pop chart, providing a sign that Elvis’ aim may not have been to make hits above all else, but to do something more personal, a goal reflected in the other non-gospel, as well as the gospel, numbers recorded during the May sessions: all covers and none written by the coterie of songwriters that had been composing the bulk of his songs since the start of the sixties.

One, an informal interpretation of the Hawaiian ‘Beyond the Reef’ (not released until 1980) replicated the home recordings Elvis had been making with Red West and Charlie Hodge. Another, ‘Fools Fall in Love,’ mined the McPhatter songbook a second time. The final two appeared as bonus tracks to pad out the Spinout soundtrack and represent a peak of the sessions as well as a chance for an important consideration of what Elvis was doing here.

‘Down in the Alley,’ originally recorded by the Clovers, is a colossus: the drums of Harman and Fontana providing a rhythmic backdrop of ferocious depth, Randolph’s saxophone taking the closing to a whole new level by tonguing his notes over the final recitations of “Janie Janie Janie Janie Jane Jane” by Elvis and the Jordanaires.

A contrast is Bob Dylan’s ‘Tomorrow is a Long Time,’ one of the songs he had written that he did not include on any of his albums but among those promoted by his publisher for others to interpret. Among those who did were Ian & Sylvia and, most profoundly for Elvis, folk singer Odetta Holmes, known simply by her first name. Odetta’s 1965 album of Dylan covers captivated Elvis even as he was generally ambivalent about Mr. Zimmerman the singer. Dylan was far less qualified when he called Elvis’ ‘Tomorrow is a Long Time’ his favourite cover of one of his songs. Odetta’s guitar-driven treatment is the blueprint for Elvis’, down to copying the moans she employed before launching into the first of four verses. Again, Elvis’ vocal is explicitly centred around his deep knowledge of the source material: both the song and Odetta’s conception of it.

The question then arises: is Elvis here being an interpreter or imitator? In particular, when considering these recordings, the versions that Elvis was recalling, with the exception of ‘Beyond the Reef,’ were all by Black artists. Was it cultural appropriation or something more nuanced, more the result of the wellspring of sources that, when he was at his best and fully engaged in the art of record making, inspired Elvis. Perhaps it is prudent here to declare that it is impossible for me to ponder this question without admitting some sort of bias—a reality borne of a lifetime of listening to this music. What I hear is most certainly not above-average karaoke or well-honed celebrity impression but fully realized and deeply personal performances. They don’t sound like Elvis merely copying another’s approach to the song. Instead, they reveal the degree to which Elvis had absorbed these recordings. They are peeks into Elvis’ artistry, his keen sense of taste at its most astute and his deeply honed instincts for songs to which he could add something. Even if some level of bias leads me inexorably to this conclusion, the argument is strengthened when applied to the primary reason why Elvis was in Nashville in May 1966: the recording of his second full-length gospel album, How Great Thou Art.

“I been down on my bended knee, talking to the man from Galilee”

“I may be expressing through you beautiful symphonies of sound, color or language, that manifest as music, art or poetry, according to human terminology, and which so affect others as to cause them to acclaim you as one of the great ones of the day.” - The Impersonal Life, Joseph S. Benner

If his earlier sacred effort, His Hand in Mine, evoked the intimacy of a country church, families gathered around the home piano singing in harmony and thumbing through mother’s dog-eared hymnal, How Great Thou Art conjures a mighty cathedral, stained-glass windows, columned stone reaching to the heavens, awe and wonder yet offering to the individual, despite its size, the possibility to be forever changed.

The title track, among the most well-known of hymns, opens the album. Employing an arrangement popularized by the Statesmen Quartet, in which the form is first verse-third verse-chorus-chorus, it begins with a choral invocation by the Jordanaires, the Imperials, Kirkham, Page and Edgin setting up Elvis to sing the first verse with deep seriousness over a rubato accompaniment—keep your ears open to hear a timpani rise up when he sings “I hear the rolling thunder.” The Jordanaires and the Imperials take over for the beginning of the third verse before Elvis brings the band in for the first of two recitations of the chorus (especially noteworthy here is how Pete Drake plays his steel guitar to sound like a violin, a timbre that is one of the most distinctive elements of the sound design of How Great Thou Art). The recording climaxes with a vocal cadenza by Elvis and the full chorus of background singers that ascends to the skies. The performance is of such conviction that when compared to what was released contemporaneously with it—the extended-play soundtrack for Easy Come, Easy Go—one may very well wonder if these were the work of two entirely different Elvis Presley’s.

‘In the Garden,’ which follows the more traditional verse-chorus structure, discards the overt waltz-like rhythm that is usually employed for a more meditative approach in congruence with the transcendence of spiritual communion implied in the lyrics. The result of such an activity pours over on ‘Somebody Bigger Than You and I,’ the first of two songs springing from Elvis’ obsession with Jimmy Jones.

The arrangement used here is taken from Jones’ recording. Henry Slaughter’s piano, Cramer’s organ and Drake’s steel guitar cushion the powerful background offered by the Jordanaires, the Imperials, Kirkham, Page and Edgin. Elvis’ vocal mirrors Jones’ basso profundo (he initially tried to sing the song in Jones’ range but when reaching the impassioned bridge, his pitch wobbled which necessitated the key to be raised) and constructs a performance that again reflects how he used the work of others as a springboard for profoundly personal statements. Rarely did Elvis sing with such stirring power and feeling as he did on ‘Somebody Bigger Than You and I.’ It ranks among his very best recordings.

The feeling continues with a reverent interpretation of ‘Farther Along’ (one wishes that Elvis had not limited himself to just two verses of it, though, as those two verses took four minutes to sing, one understands why that decision was made) and through ‘Without Him,’ with a build to a thunderous crescendo, a thrilling demonstration of the immense yet intimate sound created by Elvis and the 11-voice background choir.

Sandwiched in between is the quiet ‘Stand by Me’ which harkens back to the more delicate moments of His Hand in Mine. With just Cramer on piano and Bob Moore’s bowed bass, Elvis’ hushed prayer is answered by the Jordanaires and Kirkham—her beautiful soprano soars above during the B section of the second verse—with everyone else more sensed than heard. There is a stillness here, a feeling that the spirit had entered Studio B; a realization that undoubtedly led to Elvis’ request for the lights to be turned off while they were recording what is arguably the most moving performance on the album.

Side one of How Great Thou Art was reserved for stately hymns—Episcopalian in feel. Most of side two discarded stateliness for soulfulness—its’ first five tracks a dizzyingly succession of a Baptist beat that turned Studio B into an Amen Corner. Jimmy Jones is the source for the arrangement of the venerable ‘So High.’ Elvis had internalized his recording to such an extent that he keeps in Jones’ transposing of “streets are gold” for “streets are pearls” and “gates are pearls” for “gates are gold.” The tightly wound energy generated between Elvis, the background singers and the band can no longer be contained at the start of the final chorus as Harmon unleashes a snare fill at the start of the final chorus before dancing a rhythm on the ride cymbal. A subtle, finger-snapping jazz feel distinguishes ‘Where Could I Go But to the Lord,’ as does Elvis’ vocal which is light and full of ease, casually laying behind the beat, adding colourations and shadings to the lyrics throughout—hear the short pause he adds in between “comfort I get” and “from God’s own word.” ‘By and By’ is an ensemble triumph and Drake’s fuzz-tone steel lends a creative, contemporary touch to the gospel standard.

‘If the Lord Wasn’t Walking By My Side’ pulls from the songbook of the Imperials. Written by their pianist Henry Slaughter, it’s a showcase for Jake Hess’ group in which Elvis becomes an honorary fifth member (shades of His Hand in Mine’s closer ‘Working on the Building’ where Elvis is an auxiliary Jordanaire). By the repeat of the bridge, the collective forces in the studio have built a sound of polished yet powerful soul with Cramer’s bluesy organ and the thick backbeat of Harman and Fontana setting up the prize moment of the recording: at Elvis’ insistence, Hess’ mic was turned way up for the turnaround back to the verse so he could punch through in a righteous exhortation, the closest moment on record of Elvis singing with one of his musical heroes. It makes for an invaluable and exciting document.

The jubilee is capped off with ‘Run On,’ one of the finest examples of Elvis’ sense of rhythmic singing; the mannerisms of his early rockabilly days smoothed out into something closer to slam poetry preaching the dangers and perils of the route to perdition, egged on by a deeply in-the-pocket groove and the exclamations of the Jordanaires and the Imperials.

Further evidence of the striving inherent in How Great Thou Art is the tremendous climb that characterizes ‘Where No One Stands Alone.’ As Elvis and singers begin with “Hold my hand, all the way,” the impression is of everyone stretching heavenward, trying to achieve transfiguration while earthbound. They almost get there—the crescendo proved challenging for Elvis and necessitated a work part to be appended to an earlier take. They get far enough though to induce goosebumps. The album concludes “by popular demand” as proclaimed on the back cover, with ‘Crying in the Chapel.’

Released a month prior to Easter in 1967, How Great Thou Art charted no better than the soundtrack albums of the previous year but proved to be an enduring catalogue item and netted Elvis his first Grammy Award. An all-religious album may not have been what his fans had been longing for but those who casted their reservations aside could not deny that he recorded an album that fulfilled the aspirations and drive that went into its making and this his voice—richer, deeper and more expressive than ever before—fit perfectly against the mighty sonic bed of musicians and singers backing him. The sound is large but never bombastic. It is always in service of the song.

“Your voice as soft as the warm summer breeze”

That this approach was worth further investigation is clear with another session scheduled two weeks after the May 1966 sessions concluded. June 10 brought back most of the musicians and vocalists from May with a few exceptions: guitarist Harold Bradley, pianist David Briggs and tenor saxophonist Rufus Long were booked in place of Charlie McCoy, Cramer and Randolph. Also not there was Elvis, who was under the weather and sent Red West in his place to lay down guide vocals for him to replace two days later.

Three songs were recorded, two of them for new singles: ‘If Everyday Was Like Christmas’ for the holiday season and written by West and ‘Indescribably Blue’ which came out early in 1967 and sneaked into the Billboard Top 40. The former should be better known than it is while the latter suffers from excess, an overly dramatic vocal by Elvis and backing vocals that are just as thick. The ending, however, is marvelous—its sudden apocalyptic roar sounding no less than the world caving in on Elvis.

The third track, destined to languish on the Spinout soundtrack, is where everything gelled. ‘I’ll Remember You,’ written by legendary Hawaiian singer-songwriter Kuiokalani Lee, is a deeply rhapsodic ballad. Young’s finger-picked guitar and Harman’s bongos set the table for Elvis to plump the depths of Lee’s melody. The Jordanaires, the Imperials, Kirkham, Page and Edgin add to the lushness, especially in the instrumental interlude edited out for its initial release but restored in 1993 for the box set From Nashville to Memphis: The Essential ’60s Masters I. It begs for a continued exploration of this sound, but that would have to wait three years and a return to live performances in Las Vegas where the aesthetic was more spectacle than subtlety.

Wait is also an apt word to use here in Elvis’ quest to break the cycle of movie music. He recorded only twice more in 1966: later in June for the Double Trouble soundtrack and in September for the Easy Come, Easy Go soundtrack. Both were taped on a movie soundstage and the impersonal setting led to music of the same quality. Returning to Nashville in February 1967 for the soundtrack to Clambake brought the dichotomy of Elvis to full bear: amongst the deeply twee ‘Confidence’ and the ode to boat refurbishment ‘Hey, Hey, Hey’ (a reference to Goop long before Gwyneth Paltrow put an entirely new spin on the word) were fine ballads like ‘The Girl I Never Loved’ and ‘A House That Has Everything.’ A month later, a brief session was scheduled to flesh out a demo that Elvis had recorded with Charlie Hodge of a tune that had seized his interest, ‘Suppose.’ He would give it another go in June during the sessions for Speedway.

The positive momentum of 1966 had given way to the stagnation of 1967 in which, save for How Great Thou Art, sales were dwindling and Elvis’ records were charting further and further down the Billboard charts. Marriage and a sudden interest in the ranching lifestyle were diverting his attention. An attempt to try something entirely new, working with the Wrecking Crew: the roster of musicians adding their touch of magic to the music of everyone from Frank Sinatra to the Beach Boys, was abruptly abandoned. Instead, Elvis headed back to Nashville in September. As was the case the year previous, he took inspiration from what was on his turntable.

“Guess who's leadin' that five-piece band? Well, wouldn't ya know, it's that swingin' little guitar man”

Jerry Reed hailed from Alabama and had spent years scuffling around the periphery of the music business before Chet Atkins signed him to RCA. Reed, a singer, songwriter and an especially lithe guitar finger-picker, was in the mold of Roger Miller, appearing on the surface to be a country clown but as capable of extracting pathos as he was of bathos in the deeply inventive songs that he seemed to be able to write at will. ‘Guitar Man,’ which was Reed’s most recent RCA release, told a very American, very Chuck Berry-like, rags-to-riches tale of a musician seeking fame and fortune while crisscrossing the heartland of the US of A, a story mirroring Elvis’ own meteoric rise. Perhaps that’s why it caught his ear and why he wanted to record it.

There was a hitch in the plan, however. No one was able to replicate Reed’s motoring guitar part. Producer Felton Jarvis got on the horn to track down Reed himself to play it. According to Jarvis, Reed walked into Studio B looking “like a sure-enough Alabama wild man.” Elvis exclaimed “Lord have mercy, what is that?” “I hooked up that electric gut string, tuned the B string up a whole tone, and I tuned the low E string down a whole tone, so I could bar straight across, and as soon as we hit the intro, you could see Elvis’ eyes light up,” Reed once recounted. “He knew we had it.”

With Reed providing the motor, and Scotty Moore, Young and Bradley the acceleration, Elvis’ ‘Guitar Man’ is an infectious, acoustic son of a gun. Elvis lightens up his approach to let the guitarists take centre stage. By the time of the master take, the feeling generated was so good that after the final Reed guitar break, Elvis eventually breaks into an impromptu ‘What’d I Say.’ When he sings “Yeah, a one more time,” all four guitars take the intensity level to a fever pitch.

Not wanting the lightning struck in the bottle to be extinguished too quickly, Reed stuck around for one more tune and provided the grooving opening to a cover of Jimmy Reed’s ‘Big Boss Man.’ While the final product may have been a bit more tepid than ‘Guitar Man,’ it suggests that Elvis was allowing his instincts and interests to guide the day.

Within the first few hours of the session, his next two singles were in the can and if neither was destined to be a hit, they signaled a continuation of Elvis’ search for new directions that first and foremost, satisfied his artistic urges.

The remainder of the session was in the spirit of tentative looks ahead and nostalgic nods to the past. A cover of ‘Hi-Heel Sneakers’ was one of the grittiest and toughest sounding things Elvis had ever recorded: Harman and Fontana generating an earthquake of force on the drums, and Randolph's tenor and McCoy’s harmonica riffing insistently behind Elvis. ‘Just Call Me Lonesome’ was as overtly country as anything he had ever done with Drake demonstrating his supreme mastery of the steel guitar. Elvis sat on the piano bench for an unplanned ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone,’ giving homage to Roy Hamilton and prominent place for the Jordanaires to offer thundering support.

The songs recorded in September that featured the Jordanaires had a feeling of old friends reuniting, recreating the vivid pop sound of the best of Elvis’ early-sixties records. ‘Singing Tree’ is perhaps overly sentimental but has ace support from the four, ringing piano by Cramer and elegant guitar work by Young and Bradley. ‘Mine’ and a cover of ‘You Don’t Know Me’ utilize Kirkham’s soprano to great effect, and ‘We Call on Him,’ to be twinned with ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ for an Easter single in 1968, was classic Nashville sound with a soaring lead by Elvis.

There’s music of quality here and of an impressive range. It trickled out in the coming months as singles and soundtrack-album bonus tracks (the inclusion of ‘Guitar Man,’ ‘Big Boss Man,’ ‘Singing Tree’ and ‘Just Call Me Lonesome’ on the Clambake soundtrack makes it about the most wildly inconsistent LP of Elvis’ career), a result of the RCA’s incoherent vision of how to properly package and present this music.

“My feet are itching to get back home”

A follow-up session on January 15 and 16, 1968 in Nashville didn’t help things even as the music continued to be of a high standard. It was uncharacteristically unproductive: only four songs were taped by the end of the second night. Even more unusual was an Elvis who was unfocused, often silly, just as often edgy, disinterested, and frequently and floridly profane.

With Jerry Reed on hand for both nights, his driving guitar work guided what did get recorded, including a funky cover of his ‘U.S. Male,’ with a slapping, syncopated acoustic-bass part by Moore. A stab at Chuck Berry’s ‘Too Much Monkey Business’ was good fun and a tweak in Berry’s lyrics to include a reference to Vietnam was one of the few times Elvis was even remotely political. ‘Stay Away,’ employing the melody of ‘Greensleeves,’ was a grandiose feature for Elvis and the Jordanaries while ‘Goin’ Home’ appeared to be effortless pop even as it took 30 takes to get an acceptable master.

No one knew at the time, but it would be the last time that Elvis recorded in Nashville with the original A Team, including Bob Moore, Floyd Cramer and the Jordanaires, each an integral part of his sound up to that point in his career. As such, there is an unintended poignancy to these recordings heightened by the bittersweet fact that this “final, last job” was a mostly sour experience.

The past twenty months in Nashville had seen undeniable flickers of an Elvis reinvigorated and recharged, achieving moments of artistic excellence and getting newly lost in the art of record making. And even if it didn’t bring renewed commercial success—not surprising as the aim wasn’t to chase after a hit at all costs—or effect a change in Elvis’ cultural standing—if anything, his relevancy was in further doubt at the dawn of 1968 than it was two years previously, what it did do was represent a critical prelude for the events that were to follow—the oft-repeated narrative of Elvis’ comeback—and a sign that his reemergence as a hitmaker was no fluke. In the overall arc of Elvis’ life, which is ultimately, as Baz Luhrmann’s new biopic illustrates, one of tragedy leavened by moments of triumph, his work in Nashville from May 1966 to January 1968 may not immediately come to mind as one of the triumphs but it should. For here is where his comeback really began.

Fascinating article, and it gives me new material to listen to.

I've never understood Elvis' thralldom to Parker as anything other than the awe and respect, if not liking, which anybody in Elvis' position in 1954 would have had for a conman who had been able to pull off what Elvis must have regarded as close to miraculous. It was a significant loss artistically, at least in terms of his music, that Elvis, for whatever reason, didn't dump Parker as soon as he could after Beatlemania hit. I doubt he had it in him to be the great actor he wanted to be, but with his musical instincts as solid as they were, he could have avoided the whole lamentable post 1970 jump suit follies. I had the same idea as George Harrison had long before I knew it was Harrison's idea, that Elvis didn't need the jump suits, he was Elvis, why, as Harrison said, didn't he just appear in "a black shirt and jeans and sing, 'That's All Right, Mama'?"

He never needed Parker after 1956. Every time I watch video of Elvis' first appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show, I marvel at Elvis' confidence. It amounts to audacity. There he is, 21 years old, and unlike The Beatles eight years later, he didn't have three other guys to lean on for nervous support. He was The Show, and was undeniably to the manor born.

Really enjoyed this and completely agree with your take. He had to do something to abate the mold that the movie soundtracks brought, and I’ve always thought this period was ripe to be examined in the way you did.

Came to this from your July 2023 essay (also excellent) and will go to the one on the 1960-64 material next. Thanks for your work on this.

Also, if you get the chance, read this piece I wrote: “My Grandmother, Elvis, and Me.”

https://open.substack.com/pub/glenncook/p/my-grandmother-elvis-and-me?r=727x&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web