Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn Go East

Duke and Billy's musical travelogue of the Middle and Far East

Welcome music lovers to another edition of ‘Listening Sessions.’

This time around, I’m writing about my favourite Duke Ellington recording: 1966’s The Far East Suite. The music holds a special place for me, both in terms of how it cemented a deep love of Ellington’s music and how it encapsulates the excitement of travel. I hope the below essay captures both of these points and that if you’re unfamiliar with the work, encourages you to check it out.

Coming up next will be a continuation of a piece I wrote last fall on Elvis Presley: An Elvis for Everybody, that examined the recordings he made in Nashville from March 1960 to January 1964. This time around, I will be writing about his Nashville sessions from May 1966 to January 1968, a collection of records that marked Elvis’ return to making music not earmarked for his movies, were his final work with the celebrated Nashville A Team and positioned him for the landmark 1968 NBC “Comeback” Special as well as his work in the winter of 1969 at Chips Moman’s American Sound Studios. As I will argue, Elvis’ comeback did not simply start with these two latter events, it was part of a process that started two years prior.

The Elvis essay will be a bit more extensive than what I typically write for ‘Listening Sessions,’ so there be a longer than usual break between posts. Instead of 10 days, it will be out in about two weeks after today (July 8).

Until next time, may good listening be with you all.

If you’re reading this and are not yet a subscriber of ‘Listening Sessions,’ I hope you'll click the button below to subscribe and get each edition delivered straight to your inbox. I publish a long-form essay on music three times a month, every 10 days or so.

If you are a subscriber, share ‘Listening Sessions’ with any music fans in your orbit.

“Baghdad? It was swinging.” - Duke Ellington, 1963

In mid-November 1963, a faction of the Iraqi Army launched a campaign to overthrow the country’s Ba’athist government. The Secretary-General, Ali Salih al-Sa’di, was exiled to Spain. Bombs rained on the Iraqi Presidential Palace. The Ba’ath National Guard Militia was neutralized. The Prime Minister was forced from office. The President, Abdul Salam Arif, became the head of state and a new government was formed. Though no one was directly killed in the coup, an estimated 250 perished in fighting surrounding it. In the midst of the commotion was Duke Ellington and his orchestra. When asked to describe what that experience was like, Ellington recalled it in his inimitable style of suave deflection delivered with maximum charm as “swinging.”

The Ellington band was in Iraq as part of a three-month United States State Department tour. Before Iraq, the orchestra had played Syria, Jordan, Afghanistan, India, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Pakistan and Iran. From Iraq, it was onto Lebanon and then to Turkey where politics interceded again with the news of the assassination of President Kennedy. The remainder of the tour, which was to take the band to Egypt, Cyprus and Greece, was cancelled as Ellington, Billy Strayhorn and orchestra returned to a nation in grief.

While the intersection of music with politics, and the use of the former in service of the latter, is an often dubious proposition—indeed, the reason why Ellington was sent overseas to the Middle East was to use his music and artistry as a form of American diplomacy—there is a different perspective to consider.

It’s a frame of mind rooted in travel and more specifically, why it is a laudable and potentially transformative endeavor. “Travel changes you,” Anthony Bourdain once remarked. “As you move through this life and this world you change things slightly, you leave marks behind, however small. And in return, life—and travel—leave marks on you.” Few musicians were as well-travelled as Ellington or left as deep a footprint on the world, yet the fall 1963 tour took him, Strayhorn and his musicians further afield than they had ever been, to new frontiers and cultures with opportunities to expand horizons and broaden worldviews—experiences fertile for explosions of creativity and inspiration. In the case of Ellington and Strayhorn—his greatest collaborator (during the tour, when Ellington feel ill at one point, Strayhorn took over the piano chair)—it resulted in arguably their greatest creation.

Writing in early 1964 about the process of setting what they saw to music, Ellington noted: “You have to let it roll around, undergo a chemical change, and then seep out on paper in the form that will suit the musicians who are going to play it. But it really takes quite a bit of having to decide what to do and what not to do, particularly when you have that big, wonderful and beautiful world over there as a subject. You don’t want to underestimate or understate it.” Soon after, Ellington and Strayhorn had composed four pieces to form Expressions of the Far East.

That spring, they and the orchestra toured Japan for the first time. In a special for CBS to mark the occasion, entitled Duke Ellington Swings Through Japan and narrated by Walter Cronkite, two live excerpts from the new work, ‘Depk’ and ‘Amad,’ are heard as well as a mention that Ellington and Strayhorn planned to incorporate their visit to Japan into an expanded version of Expressions of the Far East. ‘Ad Lib on Nippon,’ credited solely to Ellington, would conclude the broader work, formally named The Far East Suite, which was committed to tape in New York between December 19 and 21, 1966.

The Ellington band at the end of that year had assumed the mantle of being the most durable of American jazz institutions. Built by this time like a championship basketball team with a core group of star soloists: principally, trumpeter Cootie Williams, trombonist Lawrence Brown and reedmen Johnny Hodges, Jimmy Hamilton, Paul Gonsalves and Harry Carney, that all brought a distinctive voice for Ellington and Strayhorn to craft their compositions around and were supported by musicians such as high-note specialist trumpeter Cat Anderson and altoist and clarinetist Russell Procope to build an ensemble sound of precision infused with the spirit of Ellington that permitted the fullest execution of his and Strayhorn’s compositions. It’s a balance that when it's struck just right in basketball wins titles. In the world of jazz, it’s best summed up as the sound of Ellingtonia. Mere words, however, can only do so much to capture of the heart and soul of this music. True appreciation demands immersion.

When a listener first plunges in, what one must be prepared for is to be reconciled to an immediate future in which one is listening to not much else. The initiation in this world demands no less: absorbing the standards, the suites, the long-form works, the musicians, the metre and milieu of Ellingtonia is all consuming. To paraphrase Ellington, he loved us madly and it was felt in every note of the music. How can one listen and not eventually succumb to its seductive sonance.

For me, that happened in the summer of 2000. The Far East Suite, more often that not, provided the soundtrack for the long transit ride (usually, one bus and three subways) to a summer job at the CN Tower, an intense digestion of the nine pieces that made up the work. Back then, it felt like the score to a movie full of intrigue and romance, so vivid were the sound portraits that were created, a memorialization of individual moments that capture the essential wonder of travel, whether it was Lebanon’s Mount Harrisa, a mynah bird that caught Strayhorn’s eyes and ears or the overpowering imagery of cityscapes and scenes that reveal themselves as living, breathing paintings. It hits as deeply and powerful now as it did then for me.

While no world traveler am I—travel since I first visited New York in the spring of 2003 has consisted of occasional trips to other locales mixed in with returns to NYC as often as fiscally possible (a travel record for which I have no regrets)—the greatest thrill for me when travelling is after touching down at my destination, getting off the plane and walking into the terminal and onto customs. The build-up and excitement have culminated in the satisfaction of knowing that I have arrived and am at the very beginning of an adventurous experience.

‘Tourist Point of View,’ which commences The Far East Suite, captures the purity of that moment. The initial rush of the band approximates the landing of the plane, the first minutes after disembarking symbolized by the polyrhythms of drummer Rufus Jones, the snake-charmer line by baritone saxophonist Carney conjuring the foreign land in which our traveler, embodied by the tenor of Gonsalves, has now arrived. Responding to the probing ambiguities of the band—the clarinets of Hamilton and Procope play a particularly vital role—Gonsalves shapes a solo; there is no theme to the piece per se; of curiosity and wonder, breathy asides and sudden shouts of affirmation. There’s an abrupt detour in the middle for Anderson’s pyrotechnics and pounding fills by Jones before Gonsalves returns. After a final brief crescendo, Jones and bassist John Lamb comment on the primary rhythm of ‘Tourist Point of View,’ gradually fading into an oblivion entirely in vogue with the tune’s general feeling of mystery and awe.

Jones was new to the drum chair in the Ellington band, replacing Sam Woodyard, who had been the timekeeper since 1955, and brought a new sense of urgency and modernity to the orchestra’s sound, both key ingredients in the success of The Far East Suite. As thoroughly had Woodyard ingrained the rhythmic thrusts of Ellingtonia, one can’t quite picture him driving the climax of ‘Bluebird of Delhi (Mynah)’ with the same berserk bravado as Jones does. Equally, one can’t imagine anyone personifying Strayhorn’s musical portrait of an avian visitor to his hotel room in India as Jimmy Hamilton does on clarinet. His light and airy tone, and coquettish phrasing is such pleasing birdsong tinged with blue.

The most enduring of the compositions that make up The Far East Suite is ‘Isfahan,’ an ode to the city in central Iran. Of it, Ellington said: “It is a place where everything is poetry. They meet you at the airport with poetry and you go away with poetry.” As was occasionally the case, the tunes that populated his long-form works did not always spring from the well of the work’s inspiration—an example is ‘The Star-Crossed Lovers’ from the Shakespeare inspired Such Sweet Thunder which Strayhorn wrote before their ode to the Stratford-upon-Avon bard was in the works and had titled it ‘Pretty Girl.’ It was also thus with ‘Isfahan,’ which was written by Strayhorn prior to the Middle East tour and was called ‘Elf.’ It’s all a reminder that Ellington, who cultivated an aura of almost divinely inspired creation, was a mortal like us all.

Origin stories aside, ‘Isfahan’ is a work of genius, one of the greatest of features for the alto of Hodges, who caresses Strayhorn’s beautiful melody like the most attentive of lovers. He knows what it needs: a glissando here, a lightly held note there, a bluesy phrase after a pause putting our anticipation off the charts. Carney is also in the background lending the most complementary of support and a lush, written interlude by the orchestra almost equals Hodges’ deeply romantic performance here. A masterwork, by anyone’s standards.

A children’s dance that Ellington witnessed while on the Middle Eastern tour inspired ‘Depk,’ an ensemble triumph of joy with an irresistible melody that contrasts with the grand introspection of ‘Mount Harissa.’ Ellington’s introduction sets up the vast sweep of the piece—here are picturesque peaks and sensuous valleys set to an extended improvisation by Gonsalves, pushed by the full band to dig further into the contours of the melody. In the third chorus of his solo, he cools down before unleashing a piercing blast of notes that leads to a glorious climax by the orchestra that sets Ellington to once again take the spotlight, laying forth his modernist bona fides. He was always of his time.

Perhaps that why ‘Blue Pepper (Far East of the Blues)’ not only substitutes jazz syncopation for a straight-four rock rhythm, but has the band playing the simple blues-with-a-bridge theme like a slightly out-of-tune, modestly demented Salvation Army band, the effect not at all all dissimilar to Archie Shepp’s avant-garde deconstruction of a New Orleans brass band on ‘Mama Too Tight.’ Hodges lays down two elemental blues choruses. He must have played thousands upon thousands upon thousands of them in his lifetime yet there’s here, as always with Hodges, a freshness and simplicity that gets straight to the heart of the matter, an unflappable presence amidst the chaos especially when Anderson begins to blows the top off the joint.

The construction of the Taj Mahal provides the mystical backdrop for Carney in ‘Agra.’ His tone, both aggressive and light, arrests attention especially in a short cadenza, in which Carney alights, ever so softly, on the final note, a clinic in breath control that hints at his ability to perform circular breathing, a capability that was turned into a concert show piece for the ending to ‘Sophisticated Lady.’

The rush, the whirr and the excitement of travel is encapsulated on ‘Amad,’ especially through the jabbing, repeated-note design of the melody. The drama escalates as the trombones take over from Ellington’s piano and are answered by the trumpets—all muted—and then with the reeds calling out and the trombones responding. Everyone suddenly drops out for Jones to lay down a drumline rhythm for the first of two solos by Brown on trombone, his gruff yet clear tone reminding us we are in faraway land, charming, hypnotizing us, making the argument to get out of your seat (read: comfort zone) and go forth to see the world. After Brown’s statement, the band starts up again, culminating in the ensemble in union before a second Brown and Jones duet ends with a final orchestral chordal summation.

And then there is the magisterial finale ‘Ab Lib on Nippon,’ Ellington’s impressions of Japan in four parts. The first section is a free-form, rubato episode in which Ellington and Lamb dialogue and pick apart the opening, ascending phrase. Just before the three-minute mark, Ellington announces the transition to the next section with a ragtime interlude introducing the thematic material that the full band explores with deep intensity—hear how Hodges’ alto rides on top of the reeds in the B section making a powerful display of melodic force, an expression of Ellingtonia in all its rich and bountiful glory.

Ellington returns for a final exploration of the theme of the second part of the piece before shifting into part three, a two-minute tour de force that is an abridged history of Western music, ping-ponging from an echo of the romantic slow movement of Rachmaninoff’s 2nd Piano Concerto to the hard bop of Horace Silver to the ragtime of Willie “The Lion” Smith. There is then a moment of silence before Jimmy Hamilton enters. He plays a collection of slow phrases—perfectly formed musical sentences—to usher in the final section. Then, Hamilton switches gears to play a lickity-split line to bring the band back to play glorious punctuations; again, it’s Hodges’ alto on top; that begin a vigorous conversation between the orchestra and Hamilton, who then takes off on a solo that while it doesn’t entirely match the intensity of all that has preceded it, still thrills in its sense of drive and propulsion. A recapitulation of the final theme of ‘Ad Lib on Nippon’ closes with an ambiguous chord by the Ellington band, rather than perhaps the expected pull-out-all-the-stops conclusion.

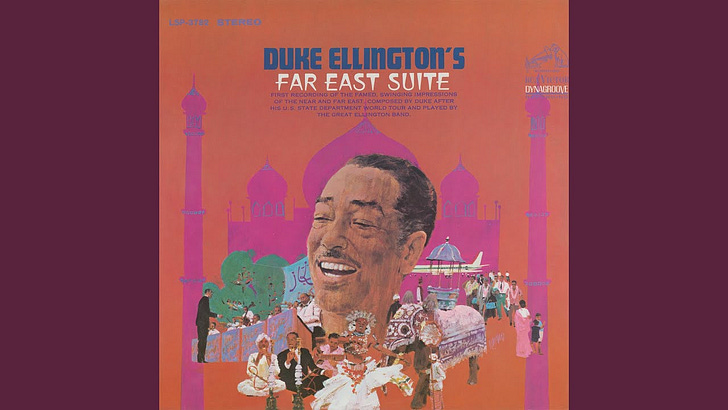

The Far East Suite turned out to be the final large-scale work that Ellington and Strayhorn composed together. Weeks before it was released by RCA Victor, Strayhorn passed away from esophageal cancer. The album cover, by titling the work as solely Duke Ellington’s, continued the unfortunate practice during their 25-year plus musical collaboration of elevating Ellington at the expense of Strayhorn.

It was another part of the cultivation of the Ellington persona, tapping into the same impulse that led him to term being caught in the middle of a political coup in Baghdad as “swinging.” It conjures a certain magic, an aura of impenetrable genius that if it blurs the distinction between the legend and the man, does little to negate the exalted position that Ellington occupies in our musical hierarchy. It’s built on the greatness of works like The Far East Suite that bring to us the world and invite us to explore it and be open to whatever wonders we may find.

Great stuff! I found this record after listening to the gorgeous 'Isfahan' -- that change to the VImaj7 chord hits you like nothing else.