Elvis 1958: Farewell to the Young Man With the Big Beat

Elvis Presley's emphatic valedictory to the sound that shook America and the world

Welcome music lovers to another edition of ‘Listening Sessions’!

I hope you are all enjoying summer and having the opportunity for quality moments of rest and relaxation.

For this edition’s essay, I turn my attention, once again, to Elvis Presley. This is the third time I have written about him and my focus this time is something of a prelude to my previous two essays that looked at Elvis’ recordings in Nashville from 1960 to 1968.

The essay just below considers the recordings Elvis made in 1958 as induction into the US Army loomed. Collectively, they are some of his finest and most fiery work. I hope you enjoy it and will share your thoughts too!

As of writing this short note, I am eagerly awaiting my copy of a newly unearthed recording of John Coltrane from the Village Gate in 1961. For my next essay, coming at the end of this month, I will share my thoughts about it as well as some other observations about Coltrane’s music in 1961.

Until next time, may good listening be with you all!

If you’re not yet a subscriber of ‘Listening Sessions,’ I hope you'll click the button below to subscribe and get each edition delivered straight to your inbox. I publish a long-form essay on music three times a month, every 10 days or so.

If you are a subscriber, please share ‘Listening Sessions’ with any music fans in your orbit.

On Friday, December 20, 1957, Elvis Presley went to Nashville. He came from Memphis to give Colonel Tom Parker a BMW Isetta the next day in Madison, a suburb of Nashville where Parker lived, for Christmas. That day, Gordon Stoker of the Jordanaires, the quartet that had been singing backup with Elvis in the studio and in concert since June 1956, also stopped by Parker’s house to get the group’s holiday bonus cheques.

Stoker and Elvis got to chatting. With Saturday night meaning Opry night, Elvis wondered if Stoker was heading to the Ryman Auditorium. Wistfully, Elvis said he would go if only he had something to wear. Stoker arranged for him to visit a clothing shop and much to Stoker’s astonishment, Elvis picked out a full tuxedo, cummerbund and all.

Elvis’ night at the Opry—revisiting the place where three years earlier, he experienced his first major setback after lightning struck on a hot summer night at Sam Phillips’ Memphis Recording Service in the form of a jittery, on-the-fly cover of Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s ‘That’s All Right (Mama)’—was immortalized in a series of photos of him with a cross section of country music’s brightest lights: Johnny Cash, Ray Price, Brenda Lee, Faron Young and others.

While at the Ryman, Elvis also saw T. Tommy Curter, who was, among other things, credited as being the first non-Memphis disc jockey to play an Elvis record. In the first part of Peter Guralnick’s definitive biography of Elvis, Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley, Curter recounts his conversation with the singer that night.

Elvis told an incredulous Curter how lonesome he felt. He elaborated: “I can’t go get a hamburger, I can’t go in some little greasy joint. I can’t go water skiing or shopping.” It was of a melancholia that Stoker sensed had enveloped Elvis. He recalled to Guralnick that at the end of the night, Elvis proceeded to change back into the clothes he was wearing earlier that day before hitting the road back to Memphis. That new tux he just bought? Stoker watched as Elvis dumped the whole thing into a barrel.

Two days prior, he had finally learned what had long been speculated: he was going to be drafted into the United States Army. In early September, guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black—the musicians who had been with Elvis since the very start—sent a letter informing him that they were going to quit working for him. The final, humiliating blow was being denied the time they had been promised to record a few tracks at the end of a three-day session at Radio Recorders in Hollywood.

While Black returned briefly into Elvis’ employ and Moore until 1968, the dispute was a manifestation of the cold, hard reality of stardom, a feeling that Elvis was feeling acutely at the end of 1957. There seemed to be a dark cloud hanging over him, no doubt aided by the insecurity—an ever-present fear that his success would suddenly disappear—that would dog him throughout his career, and often guided the decisions he made and those he didn’t.

If 1956 was designed to garner as much national exposure for Elvis, 1957 was the implementation of Col. Parker’s strategy to tightly control it and, with few exceptions, limit it to one’s record player or local movie theatre. To be sure, he was still perceived as a threat to the establishment—his recording of Irving Berlin’s ‘White Christmas’ outraged the composer, completely unaware that Elvis’ version was based on the Drifters’ recording of it three years earlier—but he was also becoming a commodity. His continued success was increasingly critical to those in his employ, both those in his entourage as well as at his home, Graceland, bought in 1957 for himself and his parents to reside.

Elvis had known since the day of his 22nd birthday, when the Memphis Draft Board confirmed his draft status as 1-A (available for unrestricted military service), that a tour of duty with Uncle Sam was just about inevitable. Equally inevitable was that Elvis would be, as much as would be possible, treated like every other soldier, something Col. Parker said couldn’t be helped even as he actively denied overtures from the Army offering to enlist Elvis in the Special Services.

His draft notice had him reporting for duty on January 20, 1958. He applied for and was granted a two-month deferment citing the hardship that Paramount Pictures would incur if the production of his next movie, scheduled to also start on January 20, was prevented from commencing. And so, on the day of his 23rd birthday, marked with a celebration at Graceland, Elvis was soon to begin the important work of ensuring that once he traded his garishly coloured civvies for a uniform, he would not be forgotten, allaying the fear, as much as may have been possible, that when he returned to American soil, Elvis would have a career to return to.

Since RCA bought out his contract with Sun Records in November 1955, his music had moved from the immediacy of the sides he had cut with Phillips for a fuller, more stylized sound, his often uninhibited energy molded into a well-oiled engine. Augmenting the core trio of Elvis, Moore and Black were the piano—most often played by Floyd Cramer, Shorty Long or Dudley Brooks—the drums of D.J. Fontana—he become the fourth member of Elvis’ unit—and, in accord with Elvis’ lifelong interest in and love of the gospel-quartet tradition, the background harmonies of one of its foremost groups, the Jordanaries.

It was on their first session backing the singer—July 2, 1956 at an uncomfortably hot RCA studio in New York—that the defining sound of Elvis on RCA in the fifties debuted. Three tracks were recorded. The ballad ‘Anyway You Want Me (That’s How I Will Be)’ would be the flip side of ‘Love Me Tender,’ the title track of his first movie. The other two, a take off on Big Mama Thornton’s ‘Hound Dog’ and Otis Blackwell’s ‘Don’t Be Cruel’ formed one of the most earth-shaking and successful singles of the early rock era.

Other signposts along the way included ‘Too Much,’ taking the raw yet controlled power of ‘Hound Dog’ even further. Fontana’s backbeat pounds like an earthquake, Moore’s guitar solo is a single-line snake charmer and Hugh Jarrett, then the bass singer in the Jordanaires, further layers the bottom, answering each of Elvis’ lines with a deep “I know.”

‘All Shook Up’ took the template of ‘Don’t Be Cruel’—it was also written by Blackwell—and introduced the element of swagger as Elvis glides through the lyrics—a harmony vocal is supplied by Stoker—while keeping the beat on a guitar case. The four gospel sides he recorded in January 1957, appearing on an EP and then added to the second side of his first Christmas album, were a signal that rock music wasn't to be his sole métier. His approach to the ballad also saw an aching vulnerability transformed into an intimate knowingness. Compare ‘I’m Counting on You’ from his first series of RCA sessions to the tour de force of ‘Don’t’ from September 1957.

These evolutionary chains, not simply the result of a concerted effort to tame his image—a Pied Piper with a pompadour leading his flock on the road to perdition—clarified what his music was to be really about and, by extension, who he really was.

An observation once made by George Harrison, reflecting on seeing Elvis live during his brief run at Madison Square Garden in June 1972, right in the middle of the jump-suited Vegas era, was his wish that Elvis would have ditched the orchestra, the choir of backup singers and gotten back to the basics of ‘That’s All Right (Mama).’ As much as that desire may be logical and understandable, it denies the inevitability of change—something that Harrison embraced as a precondition of living—and mythologizes Elvis as solely a rock-and-roller. He was most certainly not and while that would become more fully apparent in the sixties, in the first half of 1958, the records that Elvis made were an emphatic valedictory to the sound that shook America and the world. These were the records that were going to sate everyone’s appetite while he was away. Elvis, still the young man with the big beat, gave it everything he got.

The first order of business was the movie for which Elvis had petitioned a deferment. King Creole, his fourth feature, was the most concerted effort yet and, in my ways, the last, to make an Elvis movie that matched his ambition to be an actor. Directing was Michael Curtiz. The cast was formidable: Dean Jagger, Walter Matthau, Carolyn Jones, Vic Morrow, Delores Hart and Paul Stewart. The movie was set in New Orleans and while there was some shooting on location—shielding Elvis and the set from his fans proved to be a major logistical challenge—it was primarily filmed in Los Angeles on the Paramount lot.

Before shooting began on January 20, the majority of the soundtrack was recorded in two days at Radio Recorders in Hollywood. A third day was added just after shooting commenced.

The resulting soundtrack album totaled just 22 minutes of music and was the first of Elvis’ albums to be devoted solely to one of his movies (the earlier Loving You soundtrack album was padded out with five bonus tracks on the second side). It was roughly centered on a theme: exploring the connection between jump blues, New Orleans jazz, and rock and roll. That’s not, of course, to imply that King Creole was an overly conscious attempt at cross pollination. But, a way to perhaps better understand, and ultimately to contextualize, the direction that Elvis’ soundtrack albums took, something that would become far more pronounced in the early sixties, was that they were roughly thematic. Where other artists made albums of Hawaiian music, Elvis went to Blue Hawaii or of Mariachi music and Mexico, Elvis had Fun in Acapulco or of car songs, Elvis hit the Speedway to Spinout.

While all these records contained, to one point or another, the compromises that made his movie recordings the foremost exhibit for the whiplash-inducing variance in the quality of his music, King Creole distinguishes itself as containing almost none of them. It is, and take it for what it’s worth, the pinnacle of his sounds for the silver screen. It rocks, and rocks hard.

It was also the conclusion of Brill Building songwriters Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller’s association with Elvis. The two became increasingly appalled at how Col. Parker isolated the singer from those who wrote his songs. The last straw was the blowback they got when they decided to pitch a project: a filmed adaptation of Walk on the Wild Side to be helmed by Elia Kazan, directly to Elvis.

Two of the three contributions Leiber and Stoller made to the King Creole soundtrack: the title track and ‘Trouble’ explore a fusion of rock and roll with jazz. The former is refined rockabilly. Elvis dials back the mannerisms for a cool, syncopated vocal. The core group of Moore, Black, Fontana, Brooks and the Jordanaires are in the pocket. In the background, accentuating the beat, is a quartet of horn players.

On ‘Trouble,’ they are front and centre. Trumpeter Teddy Bruckner had the strongest jazz bona fides through his work with Buck Clayton, Benny Carter, Kid Ory and Sidney Bechet, and his broad, Armstrongian sound. The rest of the horn players illustrated the prominence of instrumental and mood music in the fifties and sixties. Trombone duty was split between Elmer Schneider (Bob Crosby and Alvino Rey) and Warren Smith (Bob Crosby again and Duke Ellington). Mahlon Clark (Ray McKinley and Lawrence Welk) was on clarinet and Justin Gordon (Benny Carter, Billy May, Henry Mancini and Neal Hefti) was on tenor saxophone.

‘Trouble’ is flamboyant pastiche. The verses are the blues at its most elemental, full of dramatic stops and starts, and a riff played by the horns that is a bedrock phrase of the genre. The choruses are a slow striptease, every syllable stretched by Elvis for maximum effort. The ending is a rave up, perhaps more Broadway showstopper than Basin Street second line. Elvis combines a menace that is both raw (the song was immortalized ten years later as the opening, bracing moment of his NBC TV special) and tongue-in-cheek. Where ‘Trouble’ really demand attention is in Elvis’ command. It is complete.

It boils over on ‘Dixieland Rock,’ a kind of bald rehash of ‘Jailhouse Rock,’ written by Aaron Schoreder and Rachle Frank. Elvis’ dynamo lead climaxes on the third verse. Its four lines, a sort of fifties date drama, unfold in rapid succession: “I was all pooped out when the clock struck four / but she said “no daddy, you can’t leave the floor” / she wore a clinging dress that fit so tight / she couldn’t sit down so we danced all night.”

It is set aflame on ‘Hard Headed Woman.’ Elvis’ ferocity increases at the end of each verse. The first is tightly controlled (“been causin’ trouble ever since the world began”) and the last is so loose, it’s barely intelligible (“if she ever went away I’d cry around the clock.”

The ballads display similar flare. There’s something in the way Elvis approaches the B sections of all three on the soundtrack: ‘As Long As I Have You,’ ‘Don’t Ask Me Why’ and ‘Young Dreams.’ Maybe the best way to put it is there’s a refinement, a feel that points to how his sound would shift in the early sixties. The jewel of the three is ‘As Long As I Have You’ in both its simplicity—Moore’s guitar arpeggios are unadorned and achingly sincere—and sophistication with the change in the middle eight and the closing cadenza in which Elvis traverses several octaves in his vocal range. And yet, it’s ‘Young Dreams,’ the most of the sentimental of the trio, that is of greater interest. The song’s fairytale of teenage romance, with the Jordanaires at their most extraverted, abuts against the dispiriting prospect of imminent military service as Elvis croons that “I have young arms that wanna hold you / hold you, oh so tight.”

The churn of change also surfaces on ‘Lover Doll,’ maybe the slickest thing Elvis recorded in the fifties. It would be the last recording in which it was only Elvis, Moore and Black playing. That their final collaboration—the Jordanaires’ contribution was overdubbed in June—would be something far removed from the primal force of their Sun sides is either damning proof of Elvis’ betrayal of their possibility or, as this essay is arguing, the inevitable evolution that is the arc of any artistic career.

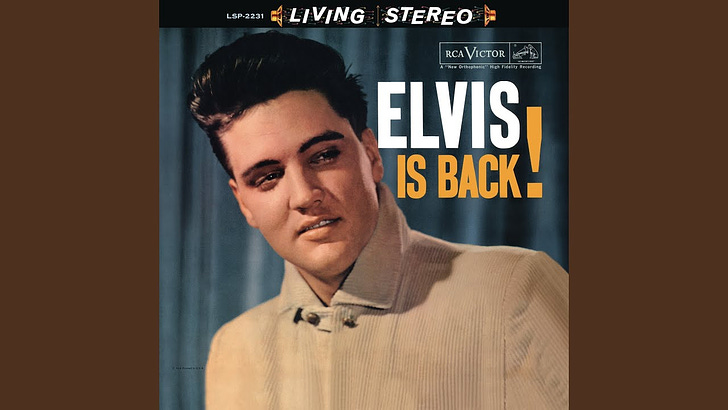

With the King Creole soundtrack recorded, the first piece of the backlog for when Elvis would be away in the service was in the can. It was, due to Col. Parker’s calculation and cunning, to be a slim one, with the least amount of product stockpiled that could be gotten away with. Its meagre quantity would be stretched by material in RCA’s vault and a reliance on compilation albums of his hits or of recordings not previously available on LP. The first of these, Elvis’ Golden Records, out in March, distilled the big bang of his arrival on the national scene into 14 canonical songs. Others—For LP Fans Only and A Date with Elvis—hinted at the casualness (it eventually tipped over into carelessness) in which his albums were created.

New, non-movie, songs were limited to two sessions. The first, in the middle of the King Creole shoot, took place on February 1. The core group from the soundtrack session was augmented by a second guitarist, Tiny Timbrell. From the session, the last time Bill Black recorded with Elvis, came a new single for the spring.

The A side, ‘Wear Your Ring Around My Neck,’ took the scenario of ‘Young Dreams’ and removed the gayety for an earnest desperation, especially in the furious bridge. The flip slide, ‘Doncha’ Think It’s Time,’ written by Clyde Otis and Willie Dixon, was a mix of the sour with the sweet. Moore’s opening guitar riff is slightly distorted. It gives way to a close and danceable beat. Elvis plots a path for each line: beginning broadly before a smooth finish with the Jordanaires. Their “ah-ha-who” backing throughout most of it is of the grey-flannel-suit variety, a tailored touch to a piece of pristine rhythm and blues.

The third cut from the session—a cover of Hank Williams Sr.’s ‘Your Cheatin’ Heart,’ one of only two times Elvis delved into the country pioneer’s songbook—is plodding and remained unreleased until 1965’s Elvis for Everyone! An alternate take on the 1977 compilation Welcome to My World is far more sprightly and energized, and would have made a good album track should there have been a studio album to include it on at the time.

The night before Elvis was to be inducted into the Army on March 24, he went out with pals and Anita Wood, his main squeeze at the time. First, they went to a drive-in to watch Sing, Boy, Sing starring Tommy Sands and then to a local skating rink. He reported, on zero sleep, to the Memphis Draft Board at 6:35 a.m. to become a solider. In 1972, reflecting back, Elvis said “overnight it was all gone, it was like a dream.” Formally inducted into the service at Fort Chaffee in Arkansas, he undertook basic training in Texas at Fort Hood. At the end of May was the start of a two-month furlough with the night of June 10 dedicated to recording at RCA’s Studio B in Nashville.

Studio B had become, along with the Quonset Hut studio run by Owen and Harold Bradley, the epicentre of the country-pop explosion of the late fifties, the so-called Nashville Sound, and a home base of the A Team, the versatile group of musicians whose talents built Music City into a southern hub of record making.

As Elvis, decked out in Army-issued khaki, arrived at the studio for the all-night session, he was greeted by a group of old and new faces. On piano was Cramer and on drums was Fontana. The Jordanaires were there too with a new bass singer, Ray Walker, who had replaced Jarrett. On bass and also on drums were the premier session player in Nashville on each instrument: Bob Moore and Buddy Harman. Some would also say the same of Chet Atkins, who was on guitar, but Atkins himself would have demurred at such a suggestion. He knew the top Nashville picker was not him. It was Hank Garland.

Garland had already played a few live dates with Elvis in the autumn of 1957 in the aftermath of Moore’s temporary resignation. On June 10, Atkins would play second guitar to Garland’s lead. It may be hyperbole to say that Garland could play anything but the recorded evidence backs that statement up. Gary Burton, as inventive a vibraphonist as there has ever been and with impeccable taste, got his start in Nashville and played jazz with Garland. Burton once said of him: “His very presence seemed to create a buzz among the musicians, whether it was country, rock or jazz.”

First on the agenda that night was ‘I Need Your Love Tonight,’ a mid-tempo rocker. Almost immediately, the rapport between Elvis and Garland comes through. By take 5 (the entire June 10 session was released in 2007 on the Follow That Dream collectors label), Elvis lets out a “yeah” as Garland solos with bright bursts of driving chords that push everyone along. Walker is also prominently featured, echoing Elvis at the end of each line of the song. Once Harmon and Fontana settle on using the toms for the rhumba-like B section on the second take 10 (it’s slated twice by mistake), all the elements are in place. On take 18, the master, Elvis’ “yeah” as Garland digs into his improvisation is emphatic. There’s something new here. A raw excitement.

‘A Big Hunk o’ Love,’ which was tackled next, undergoes a stunning evolution over the span of four complete takes. The song is a sly, slightly risqué piece. Take 1 is tentative. Harmon and Fontana tap dance on the drums, a too polite beat for lines like “don’t be a stingy little mama / you’re about to starve me half to death.” Cramer’s solo is equally far too cordial but Garland’s, especially its start with a nasty, undulating rhythm, sparks an idea. This song needs to tear the roof off the place. On take 2, Harmon and Fontana opt for a straight, faster beat. Elvis goes full urban rockabilly on the verses. Cramer is still a little too soft while Garland nails the feel, if a little too generically. Undeniably though, a spark has been lit. Harmon and Fontana start take 3 by pounding the drums like a runaway freight train. Walker adds a bass line to thicken the groove. Everyone sounds looser. On take 4, they become dangerous. Elvis’ phrasing is otherworldly, performer and material merging into a colossal tidal wave of primal sound. The Jordanaires are equally in the moment and snuggly in the pocket. Cramer’s spot is unrelenting in its propulsion with Walker wordlessly bopping every one into the stratosphere. The gloves are off. When Garland takes centre stage, Elvis repeats the end of the verse over and over off mic. As the guitarist begins his first phrase, the drummers veer into ecstatic bedlam. As he starts his second, they accent every one of Garland’s slashing chords. As he ends his breathtaking solo—Elvis is scatting along—the question is not whether Garland was the best player in Nashville but the best player period. There are only six musicians playing but it sounds like an orchestra. Even as the master is an edit of this take and the one before, the fourth and final take of ‘A Big Hunk o’ Love,’ in its raw, animalistic yet polished thrust, is the summit of Elvis in the fifties. Here is the definitive text of Elvis the rocker.

But, there was still work to be done. ‘Ain’t That Loving You Baby,’ an easy, swinging slab of r & b, proved a challenge. It was attempted first at an amiable pace with plenty of opportunity to showcase Garland as well as Harmon and Fontana. But after four takes, a gallop was tried instead. The transition from the verse, propelled by a razor-sharp backbeat by the drummers, to the chorus kept tripping everyone up. But, with each attempt, the arrangement began to gel. Everyone almost gets to the finish line on take 11 but instead of pushing ahead to realize the promise of another great record, they dropped the song. It was a regrettable decision. The second complete take of the slower version would remain unreleased until 1964 and a composite version of the faster version—there was never a complete take—finally saw the light of day in 1985.

‘(Now and Then There’s) A Fool Such As I’ was a big hit for Hank Snow in 1952 and a break from the rock focus of the session. It points forward. Elvis uses his range and expressive power to create spoken poetry out of lines like “you taught me how to love and now / you say that we are through,” letting certain words ring out, stretching others to wring their emotion and overall, accentuating the melody. In its authoritative power and the ease of everyone in the sweet spot between pop and country, ‘(Now and Then There’s) A Fool Such As I’ illustrates Elvis’ ability to elevate material and the often striking authority of his interpretations, traits that are important to appreciating what was to come in the sixties.

‘I Got Stung’ shifted back to rock. Its souped-up, sock-hop sonority catches Elvis’ interest almost immediately (at the beginning of take 4, he says “I like this song”). After Harmon and Fontana ditch florid fills for simplified transitions, everyone is cooking with grease. Take 12 could have been the master but on take 14, Garland swaps out comping in the mid range for a single-line counterpoint on the bottom. Once the balance between him, and the Jordanaires as well as Cramer is ironed out, they get the master on take 24. Throughout, Elvis motors through the lyrics, never flagging or getting tripped up, enjoying the opportunity to swing and have fun. And what that, the session—arguably the best of his career—was done.

Three days after the session wound up on the morning of June 11, Elvis returned to Fort Hood. A week later, he had his parents move into a small trailer near the base and at the start of July, he rented a home for them in Killeen where he could visit during weekends. The plan was to have a similar arrangement once he shipped over to Germany, all in an effort to make life overseas homier and bearable for all, especially his mother, Gladys.

It was not to be. In early August, she was admitted to hospital and passed away days later. It was a loss that would reverberate throughout the rest of Elvis’ life, one that arguably made his fears and insecurities even more acute.

After an emergency leave, Elvis was back again to Fort Hood. Life in the house in Killeen where father Vernon, grandmother Minnie, cousins Gene and Junior Smith, and pals Lamar Fike and Rest West all now resided, became an all-out effort to Elvis’ spirits up.

On September 19, he left Fort Hood by train for the Brooklyn Army Terminal. The evening before, Elvis spent time with friends and family, including Eddie Fadal, a Texas disc jockey whom he had befriended in 1956. At one point, Elvis asked him to lead everyone in prayer. Fadal recounted the trip to the train station in Texas to Guralnick once. “I rode with Elvis and Anita in his new Lincoln Continental, with Elvis driving,” Fadal said. “Then Anita and I drove home and sat there with Vernon for a while, We were really in mourning, he’d never been left like that before and we were [worrying]: how are they going to treat him, are they going to resent or embrace him, you know, how is he going to like it?”

Prior to shipping out on September 22 to Germany, Elvis gave interviews and held a press conference, portions of which were included on an EP, Elvis Sails. Asked just before the USS General George M. Randall pulled out from port for some final words for his fans, he said “I’d like to say that in spite of the fact that I am going away, and that I’ll be out of the their eyes for some time, that I hope I won’t be out of their minds, that I’ll be looking forward for the time when I can come back and entertain again like I did.”

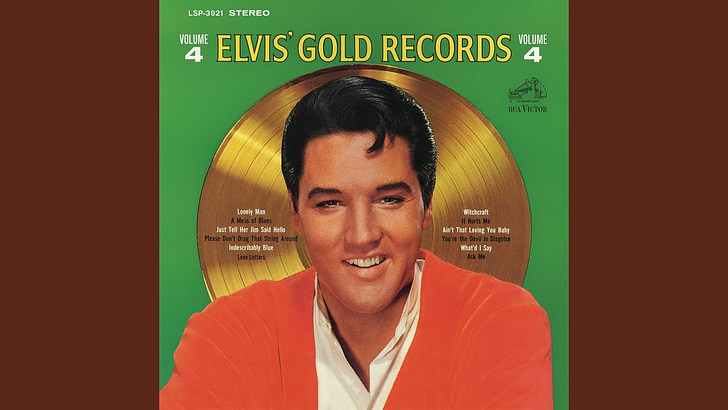

While he was away, the three singles that resulted from the June 10 session, augmented by a sanitized cover of ‘One Night,’ co-written by Dave Bartholomew and a dramatic versoin of Ivory Joe Hunter’s ‘My Wish Came True,’ both from 1957, were all double-sided smash hits, and Garland, Cramer, Moore and Harman were all to become key collaborators of Elvis in the sixties. A second greatest hits collection, 50 Million Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong: Elvis’ Gold Records, Volume 2, came out in November 1959.

By the time Elvis completed his service in March 1960, the music world had changed. The first rock era had ended. A softer interlude had begun. The young man with the big beat was to become an Elvis for everyone.

Oof. His quote about loneliness really hit me. It's wild to think how young he was when he was making all of these intricate, difficult decisions. I remember when I was in my early twenties I could hardly decide what to eat for dinner. And he had to make all these decisions with basically no road map because he truly was the first superstar.

It should be noted that Moore and Black left because of money, because they were being essentially stiffed by Parker and felt that, having helped create Elvis' sound, they deserved better. Elvis should have spoken up.