Gordon Lightfoot Passing Through the CNE

Recounting a summer Saturday night with Canada's singing troubadour

Welcome music lovers to a new edition of ‘Listening Sessions.’

Since the last time I was in touch, I had the quite humbling good fortune of having my recent essay on Nancy Wilson featured in Substack’s weekly Reads digest. Many thanks to my fellow music writer Kevin Alexander, who writes ‘On Repeat’ (check it out and subscribe here), and recommended my piece to be included.

The exposure has brought many new readers here (a warm hello to all those who have recently subscribed!) and pushed me over the 500-subscriber hurdle. So, to everyone who has joined me here and found my work worthy of your time and to appear in your email every 10 days or so, I offer a very sincere thank you. Your support and encouragement means more than I can truly put into words. It keeps me pressing ahead and for that, I am eternally grateful.

This edition’s essay is a bit different in that it’s a concert review. I recently caught Gordon Lightfoot at the Bandshell at the Canadian National Exhibition and the below essay tries to capture that experience as well as to offer some thoughts on Lightfoot, who I regard as one of Canada’s finest troubadours. I hope you enjoy it.

Coming up on the next edition of ‘Listening Sessions’ will be a spotlight on one of country music’s most zany, inventive and sensitive performers, Roger Miller, focusing on his recordings from 1964 to 1966 which took the pop world by storm.

Until next time, may good listening be with you all.

If you’re reading this and are not yet a subscriber of ‘Listening Sessions,’ I hope you'll click the button below to subscribe and get each edition delivered straight to your inbox. I publish a long-form essay on music three times a month, every 10 days or so.

If you are a subscriber, share ‘Listening Sessions’ with any music fans in your orbit.

The Bandshell stage at Toronto’s Exhibition Place is the westernmost point of the grounds of the annual Canadian National Exhibition (CNE). It offers an oasis of calm from the glorious tumult of the CNE: quarter-games of bowler roller, whack-a-mole, crown and anchor, the birthday game, beer gardens, food truck alley, colossal onions, the Food Building, booths hocking everything from hot tubs to electronic goods offered at suspiciously low prices, the lineups, the crowds, the din, the search for a patch of green space offering even a sliver of shade.

Here at the Bandshell on the final Saturday of this year’s Fair at around 3 p.m., things are more chill, if only literally. What’s going on is your standard classic-rock picnic: food on offer like tacos, burgers, poutine, BBQ and for a little spice, jerk chicken, a make-shift bar, classic rock like April Wine blared out of a speaker and especially welcome on this sweltering day, a water station.

The benches near the stage are peppered with a few diehards, most with umbrellas, valiantly trying to beat back the sun.

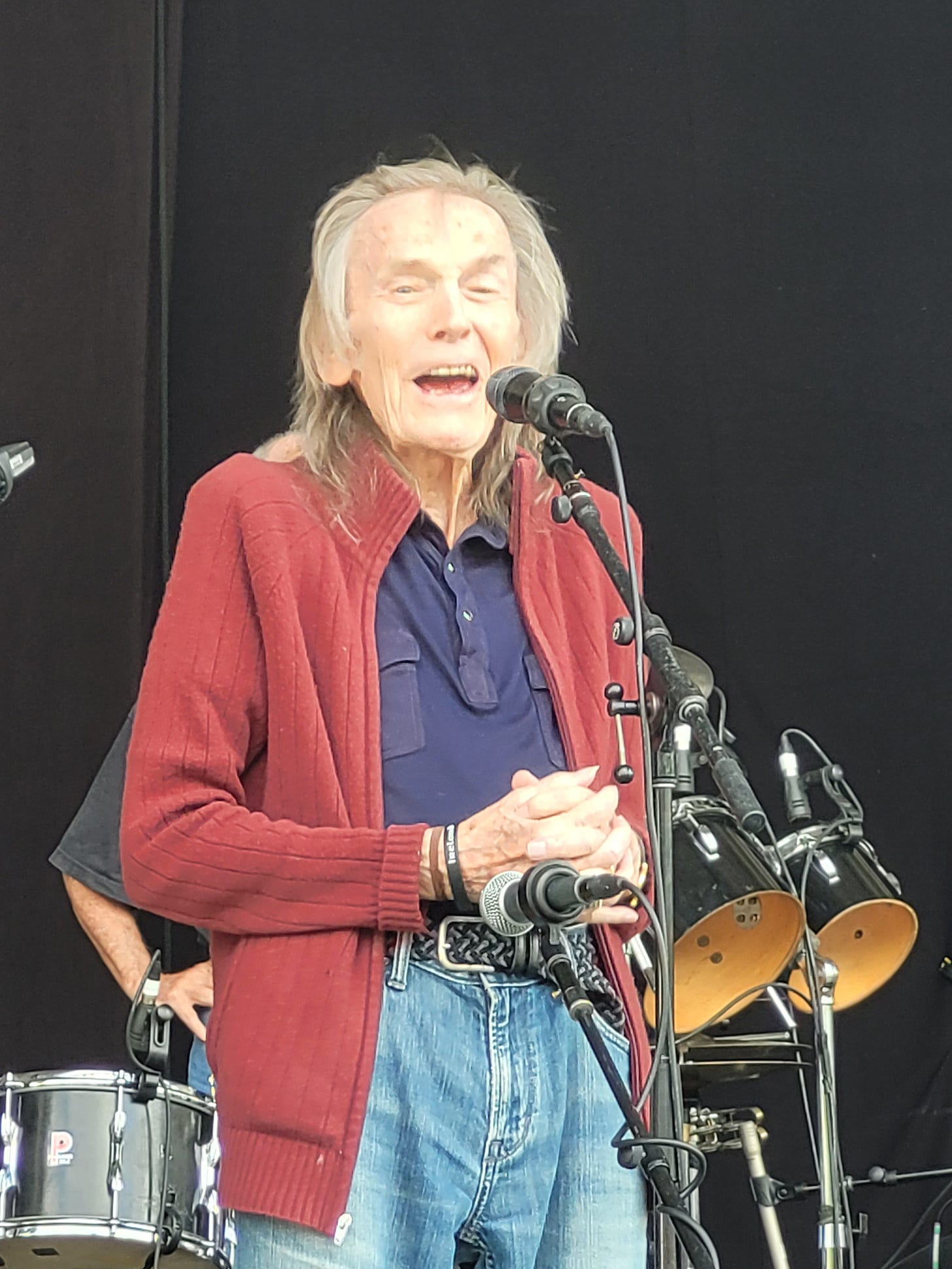

About an hour later, the front of the stage is buzzing: Gordon Lightfoot, in jeans, sports shirt and loose maroon zippered sweater, is ready for soundcheck. Bantering with the assembled crowd, cries of adulation are received humbly. I blurt out “we love you, Mr. Lightfoot” and am chided by a fan to my right for excessive formality. We agree that Gordon would have been a better salutation after mulling over Gord and concurring that would have been just a tad too friendly and familiar.

Lightfoot and band: keyboardist Mike Heffernan, bassist Rick Haynes, drummer Barry Keane and guitarist Carter Lancaster, get down to business. Few words need to be exchanged between these long-time associates—Haynes has been with Lightfoot for 53 years and counting, Keane for 47, Heffernan for 42 and Lancaster for 13 after replacing long-time guitarist Terry Clements when he became seriously ill in 2009 (he passed away in 2011). First, there’s an instrument check and then Lightfoot straps on his 12-string acoustic Gibson and launches into ‘Now and Then.’ About half-way through, he cuts the band off, switches to his six-string to get a feel for ‘14 Karat Gold’—the small crowd roars when the house sound system suddenly comes to life.

Lightfoot then sketches out ‘If You Can Read My Mind’ and stops after about a minute, declaring “too much on the low end.” Fastidious about preparing for a show, he turns his back to the crowd and faces his men as they quickly run through ‘Make Way for the Lady,’ ‘Beautiful’ and ‘Home from the Forest.’ Fifteen minutes in and they’re done—the band quickly heads back behind the curtain draped at the back of the stage. A few fans clutching LPs—multiples copies of Summertime Dream, also Endless Wire and Sit Down Young Stranger and, most tantalizing of all, a mono copy of Lightfoot’s 1966 debut on United Artists—ask Lightfoot if a roadie could take the albums, would he sign them? He says no without actually saying it. After he leaves, they plead their case to a cowboy-shirt clad member of his tour team. He mouths a definitive “no.”

There’s a certain poetry to Lightfoot playing the CNE on the eve of the first day of the annual Canadian International Air Show. Almost 60 years ago, he lamented in ‘Early Morning Rain’ “you can’t jump a jet plane like you can a freight train,” as poetic a thought as he has ever put to paper and as piercing an insight as there has ever been about the cost of modernity.

After sound check, the stands begin to fill. At 5 p.m., opening act the Good Brothers do their own sound check—at one point, Brian Good reminds the crowd to “save your applause for the show.” Once they conclude, the sound of classic soft rock fills the air—Carole King, Jim Croce, Three Dog Night (twice a Lightfoot song comes on and twice, someone quickly presses the skip button)—and a short rain storm brings some relief from the heat and humidity.

Two pass the time talking sports. Another buries his head in a book of Ezra Pound poetry. Another gently sways to the country shuffle of the Byrds’ ‘You Ain’t Going Nowhere.’ There’s a mood of late summer joviality.

For Lightfoot, summer often meant a canoe trip—a chance to clear his head and get ready to write and record a new album. Canoeing and Lightfoot are so intertwined that in 2017, he gave three of his canoes to the Canadian Canoe Museum in Peterborough, Ontario.

For some, the canoe is an explicitly Canadian way to travel and a Canadian who can master it is a Canuck to whom we can all aspire. At the risk of trotting out a fairly obvious quote by historian Pierre Berton, “a Canadian is somebody who knows how to make love in a canoe.”

Choose your representative Canadian troubadour. It may be Lightfoot, it may be someone else. No matter your choice, the following is true: while his songs are often not specifically tied to a specific Canadian locale, they are tied to Canada by a point of view, one often exploring and expressing a deep empathy for his fellow travellers on life’s journey. Consider, for example, this couplet from ‘Rainy Day People’: “rainy day people don’t hide love inside, they just pass it on.”

This summer has felt in some ways like the summer of three years ago, the hallmarks of the season returning, including the CNE, after the past two years of COVID cancellations in what may be the return to some sort of “normal” or just the prelude to whatever the autumn may have in store for us. To mark the resumption of the CNE, a parade of Canadian icons, including Bruce Cockburn, David Wilcox, Glass Tiger and Tom Cochrane, played the Bandshell. The most iconic of them all is playing this night.

While Lightfoot’s music, for me, has always had an autumnal sheen, ‘Summertime Dream,’ the title track of his 1976 album, released smack dab in the halcyon days of his commercial peak, absolutely does not.

Over a light groove that mines the grey area between folk and country, it’s a song that’s akin to ‘Afternoon Delight’—a paean to noon-time nookie without any of the camembert cheesiness of the Starland Vocal Band. Indeed, Ron Burgundy of Anchorman fame won’t be breaking out the flute to accompany such delightful Lightfoot lyrics as “so if you come ’round when the mill shuts down, you can see what chivalry means.”

Combine them with such thoughts as noting that there’s “no straw boss tallying up the hours” (turns out quiet quitting isn’t such a new phenomenon) and Lightfoot moves from the literal to the universal. It calls to mind the best that summer has to offer: a break from the routine, a chance to take a breath, a detour into a slower way of living.

A different kind of summer is harkened on ‘Summer Side of Life,’ the title track of his 1971 album, released just as ‘If You Could Read My Mind’ broke stateside. Here, the delights of the season are rendered past tense—precious moments before a group of men ship out for combat. Though the Vietnam War is never mentioned in the song and to fixate on that conflict as being the song’s explicit context is to do a songwriter of Lightfoot’s depth a disservice, it’s undoubtedly the framework in which it was initially received. The bucolic imagery of long ago (“he came down through fields of green”) abuts with the present tense, offering only “and if you saw him now, you’d wonder why he would cry, the whole day long.” Haunting then. Haunting now considering what we have all been through the past two-and-a-half years.

Maybe that’s why the Good Brothers’ opening set is so gratefully received. Hailing from Richmond Hill, Ontario, and featuring twins Brian on guitar and Bruce on autoharp and brother Larry on banjo, they’ve been making music for 50 years now. Their short set was a persuasive argument why harmony, family style (the reference to ‘Wildwood Flower’ in ‘Mom’s Song’ is a reminder of this music’s lineage to the Carter Family) is always a welcome tonic. Before closing, Brian Good declares “Gordon Lightfoot and the Good Brothers at the CNE. How Canadian is that?” and brings out Greg Keelor of Blue Rodeo for the singalong closer, Lightfoot’s ‘Alberta Bound.’

Rhapsodic calls to Canada often land as disingenuous and false—the reflexive equating of Canada with ice hockey is the textbook egregious example—but claiming Lightfoot for Canada and feeling pride at that is an exception. So when a guy in a Leafs jersey to the back of me yells “Mr. Canada in the house” once Lightfoot takes the stage, I clap in affirmation and when Kiefer Sutherland is brought out to introduce him as the last moments of dusk descend, I cut short a trip to the facilities for a bio break to cheer and hold out my phone for a photo.

Lightfoot and band get right to it with ‘Did She Mention My Name?’ Even as he struggles to push the words out—Lightfoot’s voice has gradually thinned over the years and he has emphysema, the byproduct of being a long-time smoker though he did kick the habit a few years ago—he keeps on. By ‘Ribbon of Darkness,’ which he notes Marty Robbins took to the top of the country charts in 1965, he hits his stride. There’s still an echo of the crimson hue in his voice that was most prominent in the sixties and seventies as well as that certain rhythmic lilt.

Lightfoot delights in playing the role of host and raconteur. A heartfelt tribute to the recently departed Ronnie Hawkins, who looked to Lightfoot’s songs when taking a detour into folk in the mid sixties, precedes an effecting version of ‘Home From the Forest.’ Anecdotes about Neil Young, Anne Murray and Elvis Presley are offered. Prior to ‘Rainy Day People,’ he recounts a neighbour in Toronto’s Bridle Path coming up to him while walking to share it’s his favourite of Lightfoot’s songs. He becomes especially animated when exclaiming how gratifying it is for any performer to be so warmly received in the city where he or she resides.

While Lightfoot takes the spotlight, his natty dark red velvet tuxedo jacket glistening off the stage lights, his support crew does their job while all clad in black. Heffernan’s keyboards offer extra texture to strengthen Lightfoot’s voice. Keane keeps a solid beat and Haynes does what he has done for years in the shadows: being simply one of the great bass players of our time. Few can make one note seem so consequential or a slur up or down the fretboard such an emphatic statement of the bottom. Give a listen to ‘Ode to Big Blue’ from 1972’s Don Quixote for one of countless examples of Haynes’ genius. Perhaps only Fleetwood Mac’s John McVie equals Haynes as a pop bassist so firmly in the pocket. Lancaster brings the only flash, getting up from his stool for his solos on ‘Sundown’ and ‘Baby Step Back,’ moving his guitar back and forth ever so slightly to mimic the vibrato at the end of his lines.

Trouble returns when Lightfoot becomes daunted by ‘Race Among the Ruins,’ one of several deep cuts played this night. At the end, the lights dim as he heads to the back of the stage, quipping just prior that this is his form of intermission these days and moments later, after getting a little oxygen, declares “a little squirt makes all the difference,” especially as he is about to launch into ‘The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.’ It’s a song that Lightfoot notes with pride is chronological and cinematic in its recounting of the maritime disaster that occurred on, as he makes sure to say, “the 10th of November 1975.”

Hearing it amid the dark of the Bandshell is a reminder of how extraordinary a song it is and more specifically, how Lightfoot builds a sense of impending, perhaps even inevitable, doom and how his musicians, especially Lancaster’s piercing wails modelled on Terry Clements’ on the record, Keane’s bombs on the toms and, as always, Haynes’ bass, collectively churn and roil like Lake Superior on that fateful day.

The epic beauty of the moment finds its resolution in a sparse, hushed ‘Early Morning Rain’ which, along with ‘For Lovin’ Me,’ started it all for Lightfoot. To hear him sing it for the umpteenth time, long after it has entered the canon of our greatest songs, where the lyrics can be recited by rote without any consideration of their meaning or the story it tells, is to remember that there was a time when the song didn’t exist but was brought into life and the person who did just that is here and singing it at this very moment; that in the work-a-day life of a musician the need to make and do something is, on the surface, not too much different from everyone else who toils and hopes to engender some satisfaction for their efforts and that we all in what we do create ripples of goodwill that help beat back the forces of evil in this world. But, and it’s a big but, to write a song that reaches countless millions and endures through the ages is something beyond the everyday. It is, for lack of a better word, magical.

Few have performed this task as well as Gordon Lightfoot or as humbly. And even as he has been weathered by age and at 83—his voice but a wisp of what it once was—that he still feels that he can continue to offer a good show to those who love him and can create converts out of those who are only tangentially familiar with his work is a blessing indeed.

And as he and his men exited the stage just before 9:30 p.m. and it became clear that they weren’t coming back, some remained, hoping against hope that he may play just one more song. But the road beckons Lightfoot this fall—he has 28 shows booked from mid-September to early-November. It’s time to get travelling again. The life of the Canadian troubadour continues on.

“If you want to know my secret,

Don’t come runnin’ after me,

For I am just a painter passing through history.”

- ‘A Painter Passing Through,’ written by Gordon Lightfoot

Thanks for resharing this post on the heals of Gordon's passing. His music touched me from the first time I heard him sing. I just subscribed to your Substack and look forward to perusing the entries--looks like we share some musical tastes. I've been writing about the Grateful Dead for some time and just started merging a few shows over to a new Substack of my own. Check it out: https://open.substack.com/pub/zencowpoke/p/grateful-dead-gaelic-park-bronx-ny?r=7iwom&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=email

Thanks for the mention. I'm always happy to share Listening Sessions!

For me. Lightfoot's music is an odd duality. "Carefree Highway" reminds me of being a kid in my parent's car. In those memories, it's never raining.

Today I live in Wisconsin, and it might as well be a licensing requirement that every bar have "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald" in it's jukebox. It's an event that still deeply resonates with people here even now. All you have to do is play the first few notes of the track, and watch the mood change.