Impressions of Gordon Lightfoot

Some alternate takes on our work-a-day troubadour

Welcome to a new edition of ‘Listening Sessions.’

This edition’s essay is a consideration of Gordon Lightfoot’s legacy. Stemming from both the sheer amount of time I’ve dedicated to listening to his music and a wish to probe his music more deeply than some of the tributes that came out after his passing on May 1, it grazes his most well-known recordings only in passing in favour of some that don’t necessarily come to mind as part of his canon. I hope you enjoy it and will drop a comment below with your favourite Lightfoot records.

Until next time, may good listening be with you all!

If you’re reading this and are not yet a subscriber of ‘Listening Sessions,’ I hope you'll click the button below to subscribe and get each edition delivered straight to your inbox. I publish a long-form essay on music three times a month, every 10 days or so.

If you are a subscriber, please share ‘Listening Sessions’ with any music fans in your orbit.

When the news came just after nine o’clock Toronto time on the evening of May 1 that Gordon Lightfoot had died, it, in retrospect, shouldn’t have come as a shock. The announcement on April 11 from Lightfoot’s office that a series of Florida dates planned for June, and in California and Arizona for September were cancelled and that there were no immediate plans to reschedule due to “health related issues” was the tell. Little could keep Lightfoot from the road and the stage. There was a sacred bond between him and his public. They deserved a good show and Lightfoot did whatever he could to deliver it. Retirement was never an option for him and it wouldn’t be for you either if you loved doing your job as much as Lightfoot loved doing his.

Even as the world morphs and moves in increasingly strange and bizarre ways, there have always remained some constants on which to cling: after summer comes the fall (well, maybe just me here), the sun will rise again tomorrow and every 18 months or so, Gordon Lightfoot would hold court at Toronto’s Massey Hall and his fans—happily loyal disciples—would come to pay tribute. Lightfoot was too down-to-earth, too attuned to working folk and the daily dramas of life to be mistaken as a member of a royal aristocracy but certainly in Toronto, the city he called home for most of his life and Canada, the country he choose to stay in even as could have easily pulled up stakes and headed south of the 49th parallel, he was royalty.

And yet, as the tributes have flowed and lauded his centrality to his country of birth and how his songs created a sort of national songbook, it is indisputable that Lightfoot’s reach stretched far beyond Canada’s borders. While he wrote more than his fair share of songs that were explicitly about Canada, the more intriguing characteristic about his songs, perhaps the key to why his music became so embedded with the generation that came of age along with Lightfoot as well as their progeny, is a point-of-view that so many of them advanced. Call it a keen sense of empathy or the ability to extract the poignancy of the daily struggle or a poetic eye for details that show the story as opposed to telling all of its details. No matter how you choose to term it, it helps to explain why Gordon Lightfoot always managed the make the listener feel something.

Like so many of our master musicians, Lightfoot's quest to continually get better never ceased. Even as he took the stage to perform, the cries of “Gord” ringing through the concert hall, his focus was on earning his pay, putting in a good night’s work, continually trying to prove himself worthy of the trust we had all placed in him, to justify our crowning of him as our work-a-day troubadour.

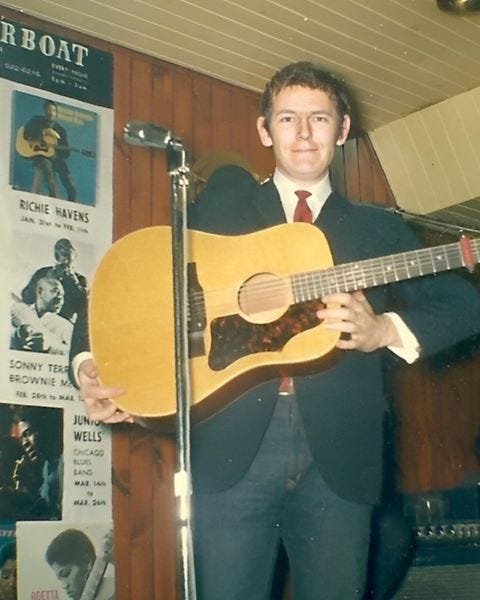

There’s a photo that was shared on social media of Lightfoot in 1967—those halcyon days when he was the toast of Yorkville—at the Riverboat Café. Lightfoot is nattily attired in coat and tie, and clean shaven. His hands grip the main body of his guitar. It’s both an unassuming photo—Lightfoot projects no airs—and one that is deeply romantic in that it captures all that is aspirational and beautiful about anyone who sets out to the big city to chase a dream and finds it coming true. Or, as Burton Cummings recounted when he and Randy Bachman were inducted into the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame by Lightfoot, that after seeing him at a Montreal coffee house in 1967 playing a set of all songs he had wrote, Cummings nudged Bachman and said, “one day, man, we’ll be able to do that, one day.”

“Edwardian, slightly striped

His hair blondish and poetic

He is less than vinyl perfect

His foot is a precise anchor for the husk and vibrance of his voice.”

- from ‘Lightfoot,’ written by Burton Cummings, Randy Bachman and Ron Matheson

While Lightfoot came of age in one of the hearts of the sixties counterculture, he could never be mistaken for part of it. And yet, his portraits of that milieu were affecting and keenly observed. ‘Go-Go Round,’ which closes the first side of his second album, The Way I Feel, may seem on the surface to be tinged with the crass misogyny that eventually led Lightfoot to cease performing ‘(That’s What You Get) For Lovin’ Me.’ Probe a little deeper and what you have is a quite touching tableux of striving bohemia. There’s a musician who catches the eyes of the song’s protagonist, a go-go dancer new to the city from a small town as well as the very sixties scene of the girl dancing for him “although a hundred eyes had turned her way.” They connect and then he leaves her for a gig in Michigan “with a group they call the Intended.” The beginning of ‘Go-Go Round’ captures our heroine in the aftermath of their failed relationship. Lightfoot paints the scene with care: “along upon the sidewalks of despair / ’twas there she wandered / with her suitcase in her hand / her fate, she pondered.” The lightly folk-rock backing by stalwarts Red Shea on guitar and John Stockfish on bass with Nashville’s Kenneth Buttrey on drums adds to its beauty. Consider how this scenario would have been portrayed if the Rolling Stones had tackled it. Well, think of ‘Under My Thumb’ or ‘Stupid Girl’ and you’ll have your answer.

Lightfoot’s songs from the late sixties that touch on love were often of a haunting nature. The dissolution that attends ‘The Last Time I Saw Her’ from 1968’s Did She Mention My Name? is almost operatic in its despair as he makes line like “I would tear the threads away / that I might bleed some more” soar. There’s also the anticipation to be reunited with ‘The Mountains & Maryann’ at the end of a long road trip and how the final ambiguous chord comes out of left field to seemingly shatter the anticipatory mood and there's the return to one’s hometown only to wonder ‘Did She Mention My Name?’

There’s also solidarity with the denizens of a city, the stories they carry out as they live out their lives in the bustling metropolis. ‘Does Your Mother Know’ (spoiler alert: my favourite Lightfoot recording) evokes concern but not in a parental way though. A song about one of the countless who sought promise in a counterculture hotbed like San Francisco, it presents the facts instead of the legend as it was in Scott McKenzie’s ‘San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair).’

They are presented evocatively. Consider the primary refrain: “But the letters that you write / in the faded winter light / just tell her, they tell her / that you’ve got ten dollars and your rent costs eight / and when you get straight, you’re gonna come back east someday.”

A layer of strings, arranged exquisitely by producer John Simon, add to the melancholic feel and the rich tapestry of the drama Lightfoot lovingly weaves. While Sundown is justifiably seen as the apex—commercially, most certainly—of Lightfoot’s oeuvre, Did She Mention My Name? is him at his most rhapsodic and maybe also at his most mystical. ‘Something Very Special,’ with the light psychedelic touch of a guitar ping-ponging from left and right is the inverse of both ‘Go-Go Round’ and ‘Does Your Mother Know.’ Here, it is a male perspective on a romantic partner who has slipped from his grasp or perhaps even vanished into thin air. Lightfoot, in marvelous voice—his sixties recordings showcase his honey-rich tenor to its greatest effect—relates details like “she said darling there will come a day / when I must run far away / I will go my love and you must stay” cushioned by vaguely Eastern-sounding strings care of Simon.

It mirrors the atmospheric brew of ‘Affair on 8th Avenue’ in which the smell of a certain perfume frames the tale of a tryst in New York and ‘The Gypsy’ in which one can almost smell the incense and see the shadows as Lightfoot recounts a visit to a fortune teller. Both come from Back Here on Earth, his follow-up to Did She Mention My Name?. ‘Bitter Green’ is the most well-known song on the album and another of his richly textured ballads. The lyrics are finely wrought (“upon the bitter green she was / the hills above the town / echoed to her footsteps / as soft as eider down” is a representative example) but one should listen at least once just to hear John Stockfish’s bass and his slurs up and down the fretboard, not unlike what James Jamerson was contemporaneously laying down on Motown.

It may seem counterintuitive to think that one of the most distinctive touches of Lightfoot’s music was the bottom. He was a folk singer with pop and country predilections. But, as composer Darcy James Argue astutely observed on Twitter following the news of Lightfoot’s passing, he could bring his own brand of funk as well. Part of it was in Lightfoot’s often-staccato attack on the guitar which latched on, with razor-like sharpness, to the beat, a style which dominated many of his most intriguing sides in the seventies. The other part is the value he placed on who played the bass.

Bill Lee, Spike’s father and the kind of dependable musician who appeared on a wide range of record dates, manned the bass on Lightfoot!, Lightfoot’s debut for United Artists Records. He provides a jazzy counterpoint (Lightfoot spent two years studying jazz composition) to the bluesy plea of ‘Oh, Linda.’ The aforementioned Stockfish, in addition to ‘Bitter Green.’ enlivened gems like ‘Rosanna,’ ‘Softly’ and ‘Song for a Winter’s Night’ with attentive fills and accents that brought a sense of momentum. Rick Haynes, who joined Lightfoot’s band in 1969 and remained there for over a half century, brought a solidity to the bottom. If Stockfish’s signature was the artful turn of phrase, Haynes’ was the emphatic period. Few have ever made a single note feel so consequential as he did on Lightfoot’s epic ‘Ode to Big Blue’ from 1972’s Don Quixote or the climb against the beat so affirming as on ‘Farewell to Annabel’ from the follow-up LP, Old Dan’s Records. Oh yes, Lightfoot and his band could groove.

He could also tell a tale. We all know about ‘If You Could Read My Mind,’ but how about ‘Talking in Your Sleep’ in which a secret is revealed during the middle of the night. Lines like “I heard you talking in your sleep / is there anything that I can do / I don’t believe we’ve had a word all day, about anything at all” elicit volumes through the small details, the listener entrusted to know what it all means: utter heartache, without Lightfoot ever saying it.

Then there are these four mighty lines, written for ‘The Soul is the Rock.’

“Late one night when the moon shown down

We went to the mill on the edge of the town

She wore white, I wore black

The town was sleeping when we got back.”

That’s a whole short story—shadowy yet sensual, illusive and illicit—smack in the middle of one of Lightfoot’s most enigmatic, philosophical songs. It’s foreboding (“bats in the roof, cats in the hall / dust on the stairway, gnats on the wall”) and also appears to wrestle with the eternal struggle of the head versus the heart, science versus faith, before ultimately siding with a form of the latter. By the time it appeared on Cold on the Shoulder, released in 1975, Lightfoot usually included one or two longer songs that were more expansive in scope and adventurous in form.

‘Seven Island Suite,’ from Sundown, is a high point of the epic Lightfoot. In the spirit of opuses like ‘The Patriot’s Dream’ and the epochal ‘Canadian Railroad Trilogy,’ it churns through three distinct moods, the shift from one to the next is organic, almost imperceptible. It also emphasizes how Lightfoot’s vocal approach had shifted by the mid seventies to favour the timbre—slightly pinched yet expansively robust—that most associate with him. On ‘Seven Island Suite,’ hear how his voice sings lines like “to the sunset through the blue light of a fiery autumn haze” deeply into the beat, his intonation broad and mesmerizing. The song may be a bit overly messianic in its proclamation of the spiritual emptiness of city life but it is one of Lightfoot’s best performances captured on record. Stockfish’s insistent bass playing and the ill-fated Jim Gordon's unflagging taste to the drums burnish its formidableness.

As Lightfoot’s voice thinned and he strained sometimes to get the words out—the culmination of a series of health challenges, including emphysema (he was a long-time smoker though he did eventually kick the habit)—the messages embedded in them could still ring out as when he performed ‘Early Morning Rain’ at the show he gave last Labour Day long weekend at Toronto’s Canadian National Exhibition, the last time I saw him live. The lyrics poured out of him with consideration and care. As is often the case with live performances, it was as close to hearing the song for the first time as it was going to get.

Fifty-four years earlier, Lightfoot penned the following stanza:

“If I could sing like the poets and kinds of this world

If I could rise like the wind or the tides of the sea

I would sing you to sleep my love with sweet melody

And let you dream away till the morning light returned again

To take you away from me.”

— from ‘If I Could,’ written by Gordon Lightfoot

It suggests a striving toward some ideal that he would have strongly demurred at ever having achieved even in the face of the mountain of recorded evidence that persuasively contradicted his ever-present humility.

Music writer Brad Wheeler of The Globe and Mail tweeted out on the evening of May 1 that when Bernie Fiedler, whose personal and working relationship with Lightfoot stretched all the way back to the Riverboat Café, visited him for the last time, he told Fielder, “we’ve had a good run.”

It brought to mind ‘Let It Ride,’ the first song at the first Lightfoot concert I saw. An unapologetic ode to the ramblers and rowdy men, it also includes a note of grace: “one day when I’m old and grey / and consider what’s gone by / I always will be proud of / every tear I’ve ever cried.” At the same show, part of his first run at Massey Hall since recovering from the life-threatening aneurysm he suffered in 2002, he played ‘A Painter Passing Through.’ Featuring a typical Lightfoot melody, in which a five-note phrase subtly shifts and changes over the course of each verse, it’s a moving comment on his life and his role in ours. It reflects on his younger days and reconciles with what happens when we all get old. It touches on his guardedness and the importance for him to keep doing his life’s work. He sings that he is “just a painter passing through in history.” The painter may be gone but the paintings remain. I suspect they always will.

Beautifully penned remembrance of Gordon Lightfoot. You’ve given depth and context to his music and his life that I have seen nowhere else.

Outstanding article. Thank you so much!