Johnny Cash: One Night in the Heart of the Counterculture

Cash in San Francisco, 1968

There’s a short clip of an interview with Bruce Botnick, the legendary recording engineer, discussing radio in the 1960s, in particular, KFWB in Los Angeles. He describes how the station’s expansive approach to playing popular music, whether it be Nat Cole or Love, helped to propel the innovation and creativity that marked music-making in the late 1960s.

That spirit was also alive in the ballroom scene of San Francisco and New York. ‘Combination of the Two,’ the exhilarating opener of Big Brother and the Holding Company’s Cheap Thrills, distills its energy in five minutes of super-charged joy. A night’s entertainment usually spanned a wide, diverse musical terrain. A triple-bill could consist of any of the following: Muddy Waters or the Who or Moby Grape or Booker T. & the M.G.s or the Gary Burton Quartet or Laura Nyro or the Grateful Dead or Gordon Lightfoot or the Buddy Rich Big Band or Ike and Tina Turner or Iron Butterfly or Ray Charles or Miles Davis. And that was just the tip of the iceberg thanks to the vision of impresarios such as Bill Graham.

In the summer of 1968, Graham took over San Francisco’s Carousel Ballroom from a co-operative group of four of the city’s biggest bands: the aforementioned Big Brother and the Holding Company and the Grateful Dead as well as Jefferson Airplane and Quicksilver Messenger Service, and rechristened it as the second and final iteration of the Fillmore West. Just prior to that, a country-music star came to town on Wednesday, April 24 for a one-nighter.

After perhaps the darkest period of his life, things were beginning to get fairly heady for Johnny Cash. Newly married to his soul mate, June Carter, a live album about to hit stores (the epochal At Folsom Prison), spiritually renewed and a drug habit wrestled to the ground and kicked to the curb, Cash was on his way to becoming country music’s avatar for a deeply abiding and fiercely principled integrity.

Rolling tape on the night of April 24 was Owsley Stanley, LSD-popularizer and soundman for the Grateful Dead. Joining Cash was wife June as well as the Tennessee Three: guitarist Luther Perkins, bassist Marshall Brown and drummer W.S. Holland. A small band of five in the heart of the counterculture playing compact music without an ounce of excess. The dissonance is delicious to contemplate and makes the recent release of Johnny Cash at the Carousel Ballroom April 24, 1968, which includes most of one of two sets Cash performed that night, an event.

This romantic flight of fancy—shades of Otis Redding conquering the flower children of Monterey—runs headlong into reality that this was just another concert date, countless ones before and countless ones afterwards for Cash and crew. The audience at the Carousel, estimated at only about a third of capacity, had no need for conversion. They were there for Cash the man.

Throughout the recording, they holler out requests. Gordon Lightfoot himself has his wish granted to hear ‘Forty Shades of Green.’ The audience whoops it up when Cash intones of Apache chief Cochise, “the next white man that sees my face is gonna (pause) be a dead white man” on ‘Old Apache Squaw.’ They applaud in recognition as June Carter gives a compact history of the Carter family songbook offering up snippets of ‘Wildwood Flower,’ ‘Foggy Mountain Top’ and others.

Cash makes clear that while he may have stood out like a sore thumb wandering through the Haight, he is an ally. He knows the temptation of vice, why it’s more fun to partake than to abstain but ultimately spiritually unfilling, and empathizes and casts his allegiance with the lowly, downtrodden and meek.

You hear it in the cautionary tale of ‘Cocaine Blues,’ the story of the runaway prisoner in ‘I’m Going to Memphis’ (hear how Luther Perkins digs way, way in to the shuffle beat here), the victimization of American myth-making in ‘The Ballad of Ira Hayes’ (though minus the unvarnished disgust that distinguishes Cash’s classic studio recording of it) and the astonishing mix of longing and resignation found in ‘Green, Green Grass of Home.’

Minus the larger Cash contingent of the full Carter family plus mother Maybelle, the Statler Brothers and Carl Perkins (Side bar: The idea of them all being present for this gig beguiles me, especially if they all joined forces for a gospel hymn. That’s taking dissonance to a level where the history we create in our minds often can’t compete with what actually happened.), we hear Cash the singer, a storyteller of profound directness, telling it straight from the gut to the heart of the listener. It comes out strongest on ‘The Long Black Veil,’ ‘One Too Many Mornings,’ ‘Give My Love to Rose’ and ‘Don’t Take Your Guns to Town.’

But, make no mistake, this recording is more than just a series of ballads. Cash and the Tennessee Three whip things up into a frenzy on ‘Rock Island Line,’ easing into a tune like a locomotive beginning to slowly chug out of a station and then picking up steam, the train clattering along the rails at an awesome clip heading to wherever its next destination may be.

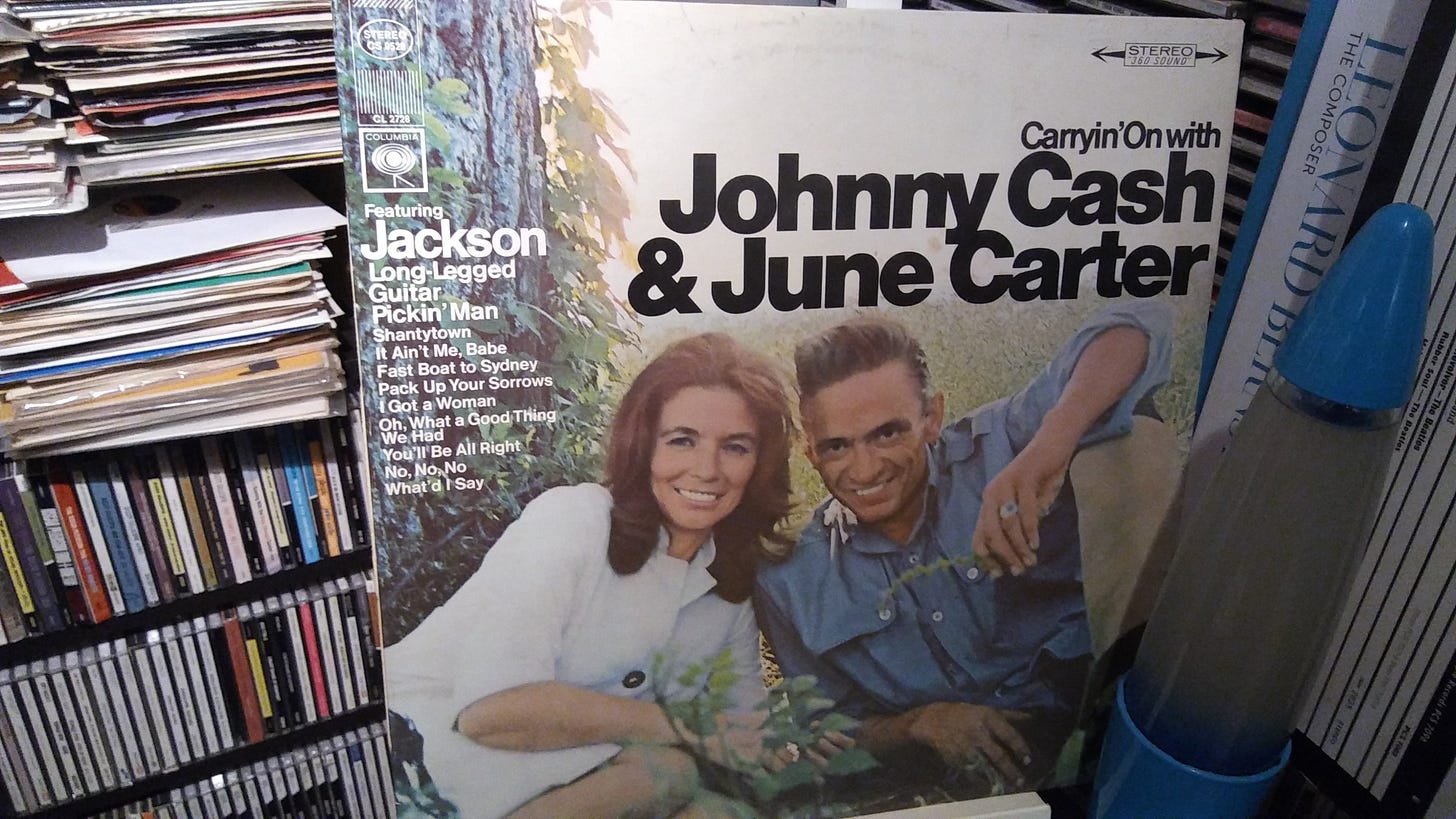

‘Jackson’ and ‘Long Legged Guitar Pickin’ Man’ are the two signature tracks on Carryin’ On with Johnny Cash & June Carter, released in the summer of 1967 and the first full-length collaboration between soon-to-be husband-and-wife. Both songs are performed at the Carousel, the former is rousing while the latter never entirely gels. On the cover of Carryin’ On, Cash and Carter are pictured outside.

Cash looks gaunt, rail-thin, outwardly portraying the ravages of substance abuse. He is wasting away but we know he is about to be reborn. It reminds us that Johnny Cash at the Carousel Ballroom April 24, 1968 is part of his redemption tale as much as it is a testament to the spirit of musical eclecticism of the late sixties and a chance to ponder the dichotomy of Cash and the counterculture. But above all, it affirms that wherever there were those who wanted to hear the truth, Johnny Cash was home.