Let's Go to Jefferson Airplane's San Francisco

Examining the great musical text of the San Francisco counterculture

Welcome music lovers to another edition of ‘Listening Sessions.’ This edition’s essay takes a look at one of touchstones of the San Francisco scene in 1967: Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow. I hope you enjoy it and will share your thoughts in the comments section.

Since my last update, I celebrated the first anniversary of my Substack. It was on May 14, 2021 that I hit publish on my first post and started to build a newsletter celebrating the joy of listening to music. At first, I planned to write a post twice a week which proved just a bit too ambitious and have settled into a rhythm of one long-form essay every 10 days or so. Over the course of the year, I have been humbled by the response that I have received and that over 200 readers have subscribed to ‘Listening Sessions.’ Thank you to you all for supporting and encouraging my work as well as providing the motivation for me to keep on writing.

If you’re reading this and are not yet a subscriber of ‘Listening Sessions,’ be sure to click the button below to subscribe and get each edition delivered straight to your inbox. I publish a long-form essay on music three times a month, every 10 days or so.

If you are a subscriber, I hope you'll consider sharing ‘Listening Sessions’ with any music fans in your orbit.

Probably the closest I’ll ever get to experiencing the Sixties in the flesh, save for the unlikely prospect that time travel will become a reality in my lifetime, was walking through the Haight in San Francisco over a decade ago. Perhaps it was the face-painted girl who boarded the bus on my way to the district or the young hippies milling outside 720 Asbury St. where the Grateful Dead once resided or the drum circle I heard near the entrance of the San Francisco Botanical Garden in Golden Gate Park.

There was a feeling of time marching backward, the scenes unfolding not some facile reenactment of the obvious stereotypes of the Sixties counterculture but a reflection of a place where the counterculture remains an ethos, a way of life. While I don’t recall hearing any music as I walked in the neighbourhood—no echoes of Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh’s recollection of sounds pouring out of every window in the evening during the Summer of Love—it wasn’t necessary. The music that we associate with San Francisco and the Haight in particular, was there. It was in the air, the ghosts of the Dead, Moby Grape, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Sly & the Family Stone and especially Jefferson Airplane supplying the unheard soundtrack set to a Joshua Light Show of the mind.

As part of my wanderings, I stopped in at Amoeba Music and soon was heading to the checkout counter with an arm’s worth of records. Among them were two firmly rooted in the Bay Area: Santana’s first and Jefferson Airplane’s breakthrough second album Surrealistic Pillow. From Amoeba, I headed right and straight to Golden Gate Park but if I had chosen instead to walk the outer perimeter of the Park, I would have eventually been on Fulton Street and came upon 2400 Fulton, a 17-room mansion that Jefferson Airplane bought in May 1968, a sign of the group’s stature as the city’s preeminent musical export at the time. One wouldn’t say that today—by 1970, the Grateful Dead had taken their place at the top, with Santana, Sly & the Family Stone and Janis Joplin a notch or two below with Jefferson Airplane primarily known for the mega hits ‘Somebody to Love’ and ‘White Rabbit’ and then eventually morphing, however improbably, into Starship and ‘We Built This City.’ Our ears have never fully recovered even if there is truth to the argument that Jefferson Airplane built San Francisco as a city of music.

The band was formed by singer-songwriter Marty Balin in 1965. Balin, among the many inspired by the evolution of folk into a harder, rock-oriented sound, wanted the band to be the star attraction of the club that he was opening, the Matrix. Connecting with Paul Kantner, another Bay Area folkie looking to embrace rock, the first edition of the band began to fall into place. Joining Balin and Kantner were lead guitarist Jorma Kaukonen—he coined the group’s name—singer Signe Anderson, bassist Jack Cassidy and Alexander “Skip” Spence, a singer and guitarist who took up the drums and became the band’s time keeper. They made an almost immediate splash in San Francisco, attracting early champions like music journalist and critic Ralph J. Gleason, who was among those in the music establishment who presciently sensed that the rock music of the era signified the beginning of a period of seismic and significant development. By the end of 1965, they signed with RCA Victor after a bidding war for their services and early in 1966 after hearing the band, Donovan name dropped them on ‘Fat Angel.’

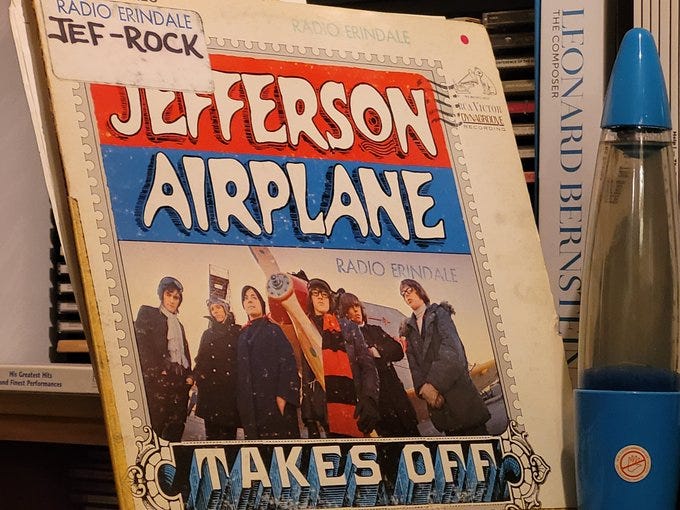

Yet, their debut album, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, released in August 1966, only hints at why they were the object of so much adulation—a 1-2-3 combination of opener ‘Blues from an Airplane’ (soaring three-part harmony by Balin, Kantner and Anderson), ‘It’s No Secret’ (the cry of Balin’s voice) and ‘Come Up the Years’ (the balance between folk and rock fusing into psychedelia) makes it abundantly clear greater things were soon to come.

By the time the album was released, Spence had left (he would soon emerge as a vital part of the explosive and combustible Moby Grape) with Spencer Dryden becoming the band’s new drummer; in October, new mother Anderson departed and in her place came Grace Slick, well known in the Bay Area as the singer in the Great Society. Within weeks of her joining, the band was back in the studio to record their follow-up album, Surrealistic Pillow. Jefferson Airplane was fully airborne. Just take a look at the album cover.

Compare to what preceded it.

There, everyone looks tentative, pensive, awkward. The visual pun of being photographed with a plane just falls flat. The cover of Surrealistic Pillow on the other hand? One word: swagger. Jack Cassidy, in the top left corner, isn’t even looking at the camera. Jorma Kaukonen, in the bottom left corner, smiles smugly, eyes hidden beneath sunglasses. The Edwardian seriousness of Spencer Dryden in the top right corner holding a banjo. Paul Kantner squinting behind a violin. Grace Slick and Marty Balin in the back, meeting the camera head on. This is a picture of a band on the rise. A band that knows it’s good. Real good. A band that is about to blow your mind. And within the album’s first minute, they prove it and then some.

Surrealistic Pillow opens with ‘She Has Funny Cars.’ Beginning with a Bo Diddley beat laid down by Dryden, we are introduced to the main sonic elements of the band: Cassidy’s heavy, rock-solid bass, Kaukonen’s lead guitar with a tone both piercing and clear and Kantner’s insistent rhythm guitar. Balin sings lead, his voice, slightly nasally and completely hypnotic, one of the greatest of the psychedelic-rock era. After the first line, Kantner joins in and then Slick completes the three-part harmony to form a formidable choir of voices. In just 45 seconds, we move from Dryden’s toms to an intersection of sound that is frighteningly good. And then it stops, and the band shifts into a two-step rhythm with Balin and Kantner trading lines with Slick, a chance for us to catch our breath. The entire sequence then repeats; this time, on the Diddley section, Cassidy has put a fuzz tone onto his bass and Kaukonen adds distortion to his guitar as if to explicitly show us that what was first good is now even better the second time around. Doubt that it could be thus? Give a gander at the album cover again. A second repeat of the Diddley rhythm includes a ripping solo by Kaukonen.

He’s a guitarist that isn’t mentioned much when considering the masters of the psychedelic ax. Kaukonen's serpentine solo lines, fluid doses of lysergic lyricism, bring delight, wonder and glorious colours. Hear how he organically emerges on the powerhouse ‘3/5 of a Mile in 10 Seconds,’ winding his improvisation through the changes of Balin’s song, playing the possibilities of the Summer of Love as well as on the follow-up, Kantner’s ‘D.C.B.A.-25,’ a poppy, catchy piece in which Kantner and Slick’s voices evocatively weave together. Kaukonen’s solo showcase ‘Embryonic Journey’ seems to anticipate the ideals of 1967’s summer and the siren song of San Francisco—young people empowering themselves to find their own way of living.

‘White Rabbit’ and ‘Somebody to Love,’ the two songs that Slick brought over from the Great Society are the messages we most remember (distort?) from the Summer of Love. The former, a marvelous, martial song building to an unforgettable climax, is a manifesto to “feed your head.” The latter proclaims the promise of San Francisco with Slick serving as town crier to those that Scott McKenzie would call to the city’s glorious vistas and winding, steep streets, all with flowers in their hair.

Both songs loom large as hit singles as well as in the context of the album, yet a pair of songs with Balin’s imprimatur hit harder as echoes of a San Francisco of long ago. ‘Today,’ written by Balin and Kantner, was Balin’s attempt to write something for Tony Bennett and while the idea of Bennett singing it would have been a simply magisterial example of cross-generational music making, that Jefferson Airplane recorded it and Balin sang it are more than ample consolation. Here again we hear the band build a performance of slow growing intensity. Balin is eventually joined in his vocal by Kantner and Slick, Dryden’s drums become more and more haunting and then there’s Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead.

Credited as “spiritual advisor” on the album’s back cover and who is also credited with coming up with the album’s title (he referred to Jefferson Airplane as playing music “as surrealistic as a pillow is soft”), Garcia’s guitar obbligato on ‘Today’ dances, whirling around in the mind, playing against Balin’s sincerity, building a song bursting forth with purity and love.

Garcia also plays on Balin’s ‘Comin’ Back to Me,’ which closes the album’s first side. If ‘Today’ reflects the promise of new love, ‘Comin’ Back to Me’ is how its ending haunts. Full of elegant wordplay (“small things like reasons are put in a jar / whatever happened to wishes wished upon a star”) and a bucolic part for recorder played by Slick, Balin sings directly to the listener, arresting one’s attention, bringing forth whatever memories may be in your mind. The song, through its use of the motif of seeing, reminds that of all its virtues, San Francisco is principally a city of views, landscapes, scenes, Shangri-La on the West Coast. Imagine if Tony Bennett had recorded this!

Its’ sonic atmosphere is echoed in ‘How Do You Feel,’ written by obscure folk musician Tom Mastin—instead of seeing, here we are asked to look. Slick’s recorder and the tight harmonies of Balin, Kantner and Slick are the definition of blissed out as is ‘My Best Friend.’ It was the first single released from the album, a month before Surrealistic Pillow hit stores in February 1967, and went nowhere. Soon, the album and, by extension, Jefferson Airplane, were everywhere. It’s combination of potent musicianship, even more potent vocal harmonies and, maybe even more importantly, concise approach to performance (only ‘Comin’ Back to Me’ pushes beyond the four-minute mark) in concert with being released at a critical moment in the American culture guaranteed its success. It was of its moment, in more ways than one.

The band’s follow-up, After Bathing at Baxter’s, almost seems like a direct provocation, its’ suite-like structure and less radio-friendly sound appearing to argue that its predecessor’s eminence was equated with inauthenticity, selling out. It also saw Balin, favouring the folk, balladic side of psychedelic music, receding to the background and Kantner and Slick, preferring edgier, more political material, moving further to the foreground. Fifty-five years later, while After Bathing at Baxter’s remains a bracing, exciting listen, especially the closing suite of ‘Two Heads’ and ‘Won’t You Try/Saturday Afternoon’, Surrealistic Pillow stands exalted, the great musical text of the San Francisco counterculture authored by its greatest musical messengers.

“We live but once

But good can be found around

In spite of all the sorrow.

If you see black

You can’t look back

You can’t look front

You cannot face tomorrow.”‘She Has Funny Cars,’ lyrics by Marty Balin

Great piece Robert. This brings back so many good memories. While at RPI in Troy NY, I was lucky to be selected for a summer course at Stanford in the summer of 1967. I wasn't really interested in the design course (our project was a more efficient shower head) but what was happening in the Haight. At the time a friend was transferring to UC at Berkeley and he drove out with my RPI room mate and we all met up. Three groups at The Fillmore for $3! The Electric Flag, Steve Miller, Gábor Szabó, The Dead for free in Palo Alto plus others. Haight St on Saturday night was a literal freak show. We had assigned reading at Stanford and went to a professor's home in the Palo Alto Hills to discuss the books. I remember the host professor saying to us "You should all go into the Haight and see what is happening there". The only downside was that there were grifters looking to rip off young innocents. We got ripped off twice. What did we know at 20 years old?

Very cool, Robert! I was someone who experienced the Sixties in the flesh, but at age 12 in 1967, the Haight, the summer of love, and the psychedelic musical output thereof was probably as far from my orbit as it all was from you and yours!

While I was all about music in '67, my record pile was British Invasion, and pretty much anyone who was featured in the Tiger Beats, Flips, and 16 Magazines I collected voraciously! I could've used this article by you in 1975, when I started spinning discs at the first of two FM rock radio stations I worked at!

I quickly had to learn what the Airplane actually sounded like (beyond the articles and reviews in the rock press of the day I was reading...like fellow Substack-er Wayne Robins!) on record before I hit the station's console chair! Thankfully, most albums were pre-marked with which cuts we jocks were "allowed" to play!

Anyway, very enjoyable trip, Robert, and thanks!🎶😎👍