Living the Good Life in New York

Chronicling four nights in the jazz clubs of NYC plus what I've been listening to recently and a check on how my Substack doing (spoiler alert: pretty darn good)

Greetings music lovers!

I’m in touch a little earlier than usual to share my first of a series of paid posts, which I aim to send every two months or so. These posts will be more personal than my ongoing series of music essays and will be a series of reflections on music in general, what I’m listening to and an update on how my newsletter is doing. For this post, the focus is on the music I heard in the jazz clubs of New York last month while I was there for a week’s holiday.

I am deeply appreciative of all those who are supporting me with a paid subscription as well as all who subscribe here. Paid subscribers help with my plans to expand the work I do here and if that’s something you feel you would like to help me out with too, I hope you'll consider doing so. Monthly and annual subscriptions are available and cost $6/month or $50/year (Canadian dollars). If funds are tight, I would be happy to comp a paid subscription no questions asked. Please be in touch by email.

My next regular post will be coming this Saturday (November 23) and will focus on Laura Nyro as well as on some of the music that was released in the late sixties and early seventies that was influenced by her.

Until next time, may good listening be with you all!

Report from New York

Midway through his second set at Mezzrow, a jazz club deep in Greenwich Village, on an unseasonably warm October Wednesday evening, singer John Dokes had an observation to make. If everyone in the small club—most of us were seated at an array of tables to his left and right—listened to one of his three albums on Spotify later that evening, he would make—and here he paused—about 14 cents, he reckoned

The numbers for Dokes on Spotify are sobering indeed. As of October 24, he had 91 monthly listeners with his version of ‘This Can’t Be Love’—he sung it during his second set at Mezzrow—his most popular track with 1,555 streams, the only recording of his to crack the 1,000-stream threshold and consequently, the only one for which he could conceivably be eligible to receive royalties from the streaming colossus.

This is of course, and sadly so, the reality for many recording artists these days. Trying to forge a living while the system is thoroughly aligned against such a thing is, in many ways, the name of the game. I first heard Dokes’ latest album, a spritely big-band album called Our Day (Swing Theory), a few months ago and thought it was fine, especially the closer, ‘Everything Must Change,’ which was initially recorded by Quincy Jones in 1974, but it didn’t muster enough passion for me to write about it. But still, when Dokes’ show at Mezzrow coincided with my annual jaunt to New York in autumn, I was excited to get a chance to see him in person.

Dokes was joined by long-time collaborator Steve Einerson on piano as well as Joseph Ranieri on bass and Alvester Garnett on drums. For both sets—I was maybe two feet away from the band—I was mesmerized. Dokes’ approach bears traces of Johnny Hartman—his range is such that his voice becomes deeply resonant when it reaches the lower register—and Joe Williams—he has a mastery of the hallmarks of Williams’ repertoire from the most recognizable (‘Everyday I Have the Blues,’ naturally) to the lesser-known (‘She’s Warm, She’s Willing, She’s Wonderful,’ for starters). He is also fleet of foot, performing a fandango during the dramatic close of both sets, Horace Silver’s ‘Senor Blues.’

All these ingredients make Dokes an interesting artist to hear live. I suppose it was the way he transformed ‘’Tis Autumn’ (Nat Cole is another of Dokes’ North stars) that impressed me most. It’s a song with a gorgeous melody. Chet Baker’s 1959 recording of it is particularly beautiful. The lyrics, on the other hand, come off as cloying and corny. In Dokes’ hands, he transformed them into an elegant ode to the season, even its most cringe-worthy line, “la de da, la de dum, ’tis autumn” was lovingly sung—maybe it wasn't quite as goofy as I thought. Anyone who does something like that is not just a singer but an artist. Listening to an album of someone singing is one thing, seeing them live is something else entirely. Count me a fan of Mr. John Dokes, please.

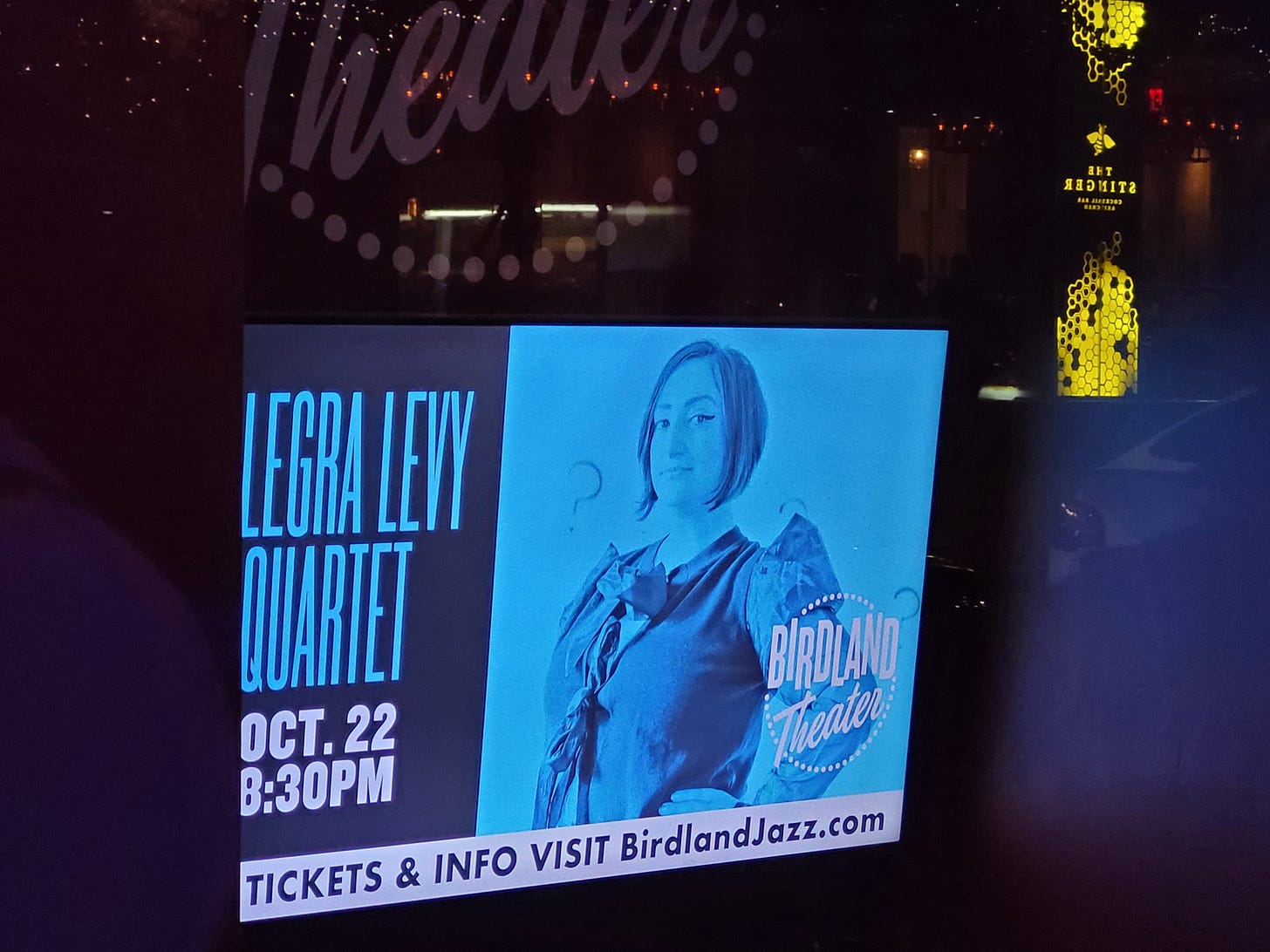

When I went to Birdland the night before to hear vocalist Allegra Levy, I was already a huge fan. Her recording from 2020 of her lyrics to a series of melodies by trumpeter John McNeill (RIP), Lose My Number: Allegra Levy Sings John McNeill (SteepleChase), is one of the best recordings I’ve heard over the past few years. At its best, it’s a deeply romantic, deeply New York small-group jazz vocal LP. ‘Livin’ Small,’ with its vision of a “cozy apartment for two / though it may not be much / there’s room enough for me and you” is a deeply felt portrait of city living. I’ve listened to it at least 100 times now.

For Levy’s set, she was joined by pianist Jason Yeager, bassist Hannah Marks and drummer Matt Wilson. It was centred around her latest album, Out of the Question (SteepleChase), a fine recording of question songs. She also graced the audience with a beautiful version of ‘Zepher’ in tribute to McNeill.

Levy saved the best for last when she decided to send us off into the night with a brittle and beautiful version of Neil Young’s ‘Harvest Moon.’ The arrangement embellished the descending line—a sigh, really—that makes the song such a sturdy piece of sentimentality. While each member of the rhythm section took delight in accenting this phrase, no one did it more movingly than Wilson. At the end, he used a small stack of paper and one of his brushes to play its swaying rhythm, lifting the paper slowly off the snare and into the air, eyes closed, squeezing every once of its sweetness like Jim Bass, the gas jockey in John Stewart’s ‘Gold’ who “got rhythm in his hands as he’s tapping on the cans.”

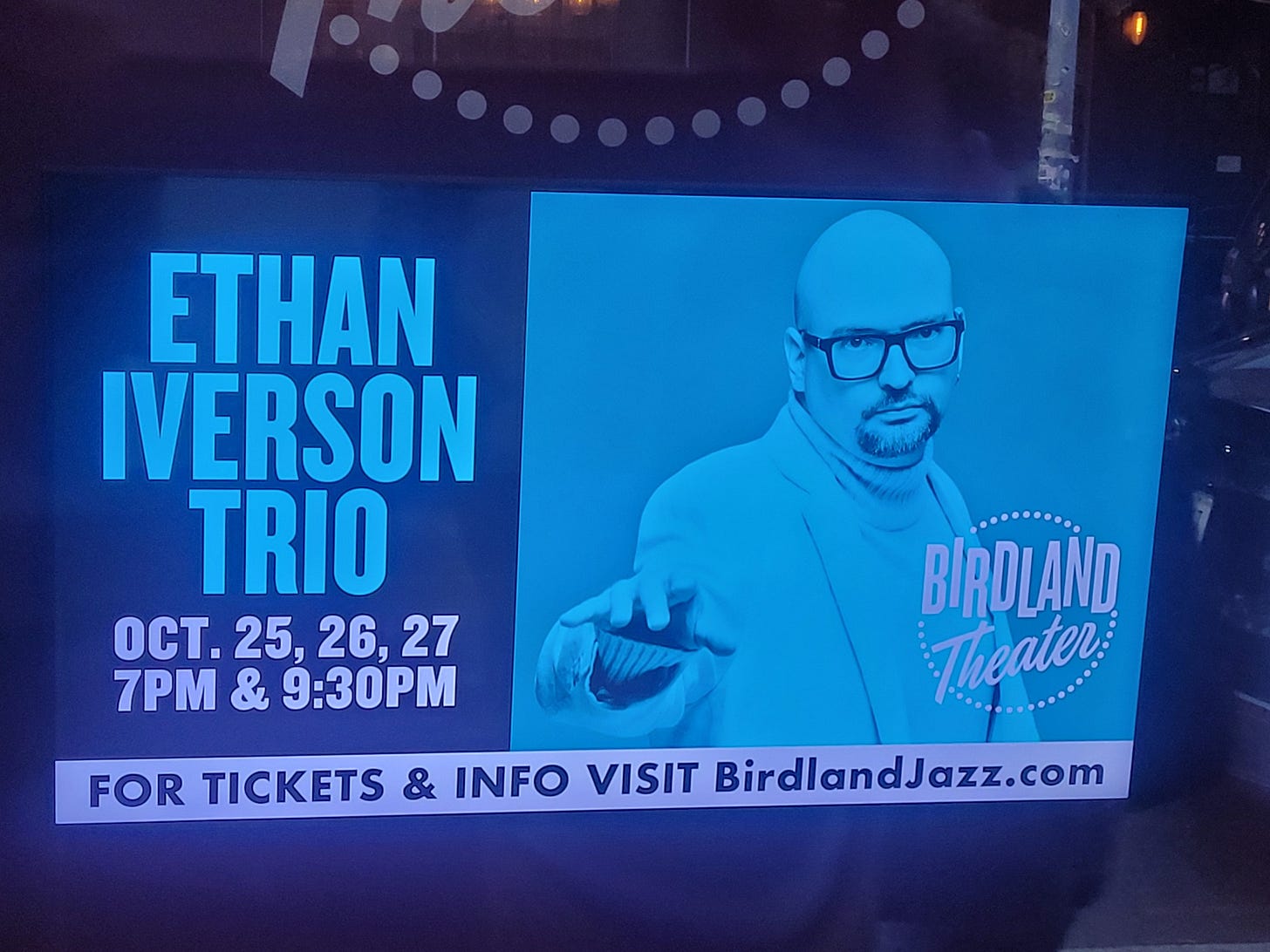

You could say the same about Peter Erskine, whose appearance at Birdland later on that week was treated as the major event it surely was. He appeared in a trio with bassist Peter Washington and the leader of the ensemble, pianist Ethan Iverson. The first night of their three-night engagement was my last night in New York and there was no way I wasn't going to take advantage of such serendipity. I caught the first set on Friday and it was simply wonderful.

The setlist Iverson prepared was eclectic and hip—one of the compositions Iverson wrote specifically for the gig was titled ‘Sergeant Hip’ for Washington and was a dialogue between him and Iverson in the vein of Ray Brown and Oscar Peterson. Iverson also played his try at creating a TV theme titled ‘She Won’t Forget Me’ and it evoked the pastel patterns of the seventies and eighties television shows that Iverson admittedly watched a lot. ‘Troubadour for Hire,’ a Burt Bacharach-like theme built around a suspended motif, remained stuck in my head for days afterwards.

The set closed with the title track of Iverson’s second release for Blue Note, Technically Acceptable, a composition that began with a Basie stroll and then, at the conclusion of Iverson’s solo, morphed into a Red Garland-like groove. Throughout, the vibe was positively serene. When the spotlight turned to either Washington or Erskine, Iverson sat at the piano bench soaking in the music, taking delight in the privilege to hear these two masters (Iverson, of course, made it three on the bandstand). For his part, Erskine would often give a subtle smile of satisfaction. These three quickly found the plane of connection.

Of course, most groups in the jazz clubs of New York are of the pick-up variety. The common grounding of repertoire and the fundamentals of the music insure things quickly fall into place with little, if any, rehearsal. Part of the fun of frequenting the clubs and taking in the music is to bear witness to this creation of spontaneous alchemy. The sight-reading of a theme. The return to the sheet music to guide one’s solo. The small gestures—a raised eye, a slight nod, the brief conference before the next tune is played to establish the key and the tempo—that make the music cook. The musicians are in the moment. The listener is vital too. Forget your phone. Forget the time. Shelve the conversation for another time. See how jazz is made. Pay attention. Watch. This knowledge is power.

I’ve learned a lot going to Smalls in the Village over the years. Every time I go to New York, I make sure to drop by. My fondest, most vivid memory of being there was Election Day, 2016. Back then, I didn’t have a smartphone. Others did and stole quick glances, telegraphing the news that was confirmed once I peeked into a bar to catch a glimpse of the news on the television just before midnight while walking back to my hotel.

Another high-stakes election lurked, even further in the background this time it seemed, as I headed down the stairs on the Thursday before Halloween, taking a seat on the bench next to the drumkit. Playing would be tenor saxophonist Troy Roberts with guitarist Paul Bollneback, bassist Massimo Biolcati and drummer Jimmy Macbride. The band began with a muscular and long version of Bacharach and David’s ‘The Look of Love’ and followed with selections from Roberts’ new album, Green Lights (Toy Robot Music), on which Bollenback and Macbride appear (John Patitucci is the bassist on it).