Miles Davis Makes His Move

How his 1968 album Miles in the Sky opened up the floodgates of change

Welcome music lovers to another edition of ‘Listening Sessions’!

This time around, I am writing about one of my favourite Miles Davis albums and quite possibly his most revolutionary or, at the very least, his most prescient recording: Miles in the Sky. That album, recorded and released in 1968, gave the first hints of the profound transition that his music was about to undertake, moving away from jazz towards jazz-rock or fusion. Davis was neither the first nor the only jazz musician investigating a middle ground between jazz and rock, and my essay delves into that as well. The topic of early jazz-rock fusion is one I would like to eventually dedicate a whole essay to and consider the thoughts offered below as a tentative start of a first draft.

I hope you enjoy the essay and will share your thoughts on it and on Miles in the Sky.

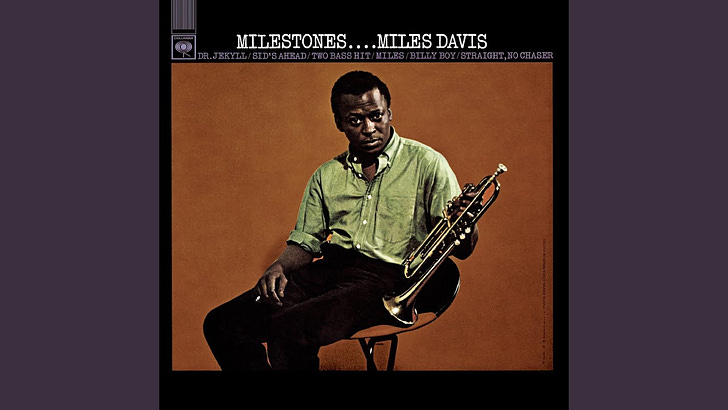

This is not the first time I have written about Davis. Last year, I discussed 1958’s Milestones which may be one of the hottest and most exciting jazz albums period. Here’s a link to it if you’d like to check it out.

Until next time, may good listening be with you all!

If you’re not yet a subscriber of ‘Listening Sessions,’ I hope you'll click the button below to subscribe and get each edition delivered straight to your inbox. I publish a long-form essay on music three times a month, every 10 days or so.

If you are a subscriber, please share ‘Listening Sessions’ with any music fans in your orbit.

Stasis is a term not normally applied to the music of Miles Davis. His music typically calls to mind movement, motion, change, an ever-present morphing so that what was locked in time by virtue of recorded tape might have already been out-of-date when reproduced on vinyl six months, if not, six minutes later. It’s a generality, to be sure, but its broad strokes are true if a little fuzzy once one gets to the finer details.

Take, for example, the extended interlude of stagnation that began after John Coltrane left Davis’ employ for good at the conclusion of the trumpeter's European tour of spring 1960 and ended at the beginning of 1963 when his long-time rhythm section of pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Jimmy Cobb called it quits. The records from that time, especially Someday My Prince Will Come and At Carnegie Hall, are great but, save for a more aggressive-sounding Davis on the latter, seem middle of the road if not just a little old fashioned, especially when compared to what jazz’s other leading lions were playing and recording at the same time.

That would of course change with the arrival of bassist Ron Carter and then drummer Tony Williams and pianist Herbie Hancock, and then tenor saxophonist George Coleman followed by Sam Rivers and finally followed by Wayne Shorter in the fall of 1964.

Albums like Miles Smiles and Nefertiti as well as the recordings made just before Christmas 1965 at Chicago’s Plugged Nickel continue to be celebrated (they probably always will be) as the great monuments of Davis’ Second Great Quintet. What they created collectively was both a deconstruction of the canonical edifies of Davis’ legacy up to that point and an erection of a small-group jazz rooted in deep telepathy and a floating, almost dreamy, mysticism. It was music that was tethered to a rhythmic pulse but seemingly—perhaps even paradoxically so—unencumbered by the harmonic or melodic structure of any particular composition. It was a thrilling, engrossing balancing act whose influence still reverberates 55 years after Davis, Shorter, Hancock, Carter and Williams began to part ways. The quintet’s dissolution was not sudden but instead a gradual erosion that began in the summer of 1968 with the parting of Carter and ended with Shorter exiting at the end of the winter of 1970.

By that time, Davis’ music had undertaken another drastic evolution. On record, it was most often dense and ambient, and played by groups of musicians often numbering in the double digits. On stage, with his core group, it was mind-melting but not, only through sheer luck, not stage-melting as well. It was the sound of Miles Davis embracing the merging of jazz with rock.

It was a stylistic marriage that started out subtly, distinct from efforts to try to find something harmonically interesting in the pop and rock hits of the day (a prime example being guitarist Grant Green’s cover of Lennon and McCartney’s ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ in March 1965 with tenor saxophonist Hank Mobley, organist Larry Young and drummer Elvin Jones) or the success Blue Note had with the so-called boogaloo beat. Instead, it was music that was thoroughly and unmistakably jazz but at the edges, there were shadings of rock.

On ‘Eighty-One,’ recorded for 1965’s E.S.P., the quintet’s first studio album, Williams used a straight beat for Davis and Carter’s theme as well as the first chorus of Davis’ and Shorter’s solos and Hancock’s half-chorus improvisation too. A second dalliance with rock came with their cover of Eddie Harris’ ‘Freedom Jazz Dance’ for 1966’s Miles Smiles with Williams again playing straight time against the theme statements and improvisations.

Davis in the autumn of 1966 was not yet concerned with finding a meeting place where jazz and rock could co-exist and neither was Harris though his original recording of ‘Freedom Jazz Dance’ from 1965 was a key track in building such a movement.

Others were more preoccupied. Drummer Chico Hamilton’s band teased out grooves that presaged the hazy, lysergic glow of early Grateful Dead—check out ‘Conquistodores’ from 1965 featuring guitarist Gabor Szabo. ‘The Dealer,’ from a year later, mined the same territory; in this case, with guitarist Larry Coryell.

Szabo and Coryell were highly impactful musicians in the jazz-rock movement. Szabo found the connection between the musical simplicity that Davis championed in the late fifties and the extended improvisations of Hindustani music that Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan were introducing to the Western world. Coryell took his inspiration from the onslaught of creativity overtaking rock since the Beatles conquered America in February 1964. Also from Hamilton’s band was tenor saxophonist and flautist Charles Lloyd whose late-sixties quartet of pianist Keith Jarrett, bassist Cecil McBee and then Ron McClure, and drummer Jack DeJohnette was a countercultural phenomenon, appearing at rock palaces like the Fillmore West and the Avalon on bills with bands like Vanilla Fudge and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

Butterfield’s group, with guitarist Mike Bloomfield, was doing the inverse of what Lloyd’s band was doing by incorporating jazz into rock forms like the landmark ‘East-West,’ a 13-minute, multi-movement raga that is both transcendent (especially the interlude after Bloomfield’s serpentine, levitating improvisation) and swirling with the promise of a new age, particularly in the slightly bossa-nova opening and the three speaker-shaking crescendos.

Another jazz group that would have been familiar to those making the San Francisco ballroom scene was the Gary Burton Quartet. Like Lloyd, Burton poked at the margins of rock, favouring an openness that encouraged intricate and rich improvisations by himself and his bandmates: Coryell, bassist Steve Swallow and drummer Bob Moses, over pulses that floated, neither jazz nor rock but something else entirely as on ‘General Mojo’s Well Laid Plan,’ written by Swallow and with Roy Haynes on drums, from Burton’s brilliant Duster from 1967.

Most of these explorations, save for guitar, used acoustic instrumentation. Joe Zawinul was an exception and plugged in with an electric piano on Cannonball Adderley’s big hits, ‘Mercy Mercy Mercy,’ and a cover of the Staple Singers’ ‘Why (Am I Treated So Bad).’ Into this hive of activity was Davis entering another period of stasis.

From the conclusion of a European Tour in October and November 1967 under the banner of the Newport Jazz Festival from which Davis left early to May 1968, the trumpeter went into the studio nine times. Some of what was attempted were fully fledged compositions, others were sketches or ideas. At seven of the sessions, the band was augmented with a guitarist (the ninth and final session had Davis working with Gil Evans and an orchestra for the final time in a studio setting); first Joe Beck, then Bucky Pizzarelli and finally, George Benson. Davis was searching for something. But what?

One clue is Hancock going electric on the first four sessions. He played a celeste on the Spanish and very lengthy (overly so) ‘Circle in the Round,’ a clavinet on the funky ‘Water on the Pond’ and electric piano on the skipping, fractured ‘Fun.’ Of the three, ‘Water on the Pond’ toys most directly with rock, especially during Shorter’s solo and the scene-setting opening, a dialogue between Beck and Carter’s doubled bass line and Hancock’s stabbing asides.

Another can be found in the sheer difficulty Davis had of getting his visions onto tape. Two of the nine sessions yielded nothing, another consisted of loose rehearsals of two major, new Hancock compositions: ‘Speak Like a Child’ and ‘I Have a Dream.’ Almost all of what was recorded would be locked in the vaults for over a decade or even longer. There was one exception.

‘Paraphernalia,’ recorded on January 16 with Benson, was another in a bevy of Shorter lines that had a mysterious hue—the main melody is a declaratory one that stops on an ambivalent resolution. The structure is knotty with an underlying groove that Benson accents. Williams’ charging hi-hat beat is mostly jazz but has a dash of rock to it.

On solos by Davis and Shorter—both are improvisations of the highest order—Williams frequently erupts in a barrage of fills ensuring trumpeter and tenor saxophonist never get complacent. Benson’s improvisation is brief, more of an interlude than a fully formed statement. Williams lightens his touch, spreading the rhythm more widely, switching the vibe from a close jazz club to an even closer go-go joint. Davis and Shorter return to repeat the theme before Hancock takes over. His touch is assertive, significantly tougher than his customary timbre in the late sixties. Just after the half-way point of Hancock’s statement, Williams plays a straight eighth-note pattern on the hi-hat, bringing an openness the defines the rest of the pianist’s remarkable statement.

Totaling just under 13 minutes, ‘Paraphernalia’ is longer than, save for the aforementioned ‘Circle in the Round,’ anything else the quintet had laid down in the studio. In any other respect, it was not a significant break from what they had been doing. But the restlessness that animated most of the sessions in the winter of 1968 would become clearer once the quintet reconvened in the studio that May.

In between a steady series of live dates in the spring, David took part in his fourth blindfold test for DownBeat magazine, a regular feature in which the test subject is played a series of recordings and asked to identify the performer and the performance, and to rate each. Critic Leonard Feather visited Davis in a Hollywood hotel room. What struck Feather, beyond Davis’ usual frosty, crusty and frequently profane put downs of much of what Feather played for Davis (of fellow trumpeter Don Ellis, for example, Davis said, “he’s no soloist. I mean, he’s a nice guy, but to me he’s just another white trumpet player.”) were the records that were scattered around the room. The Byrds, Dionne Warwick, James Brown and Aretha Franklin. No jazz at all.

And then there was also what Davis praised. Jim Webb’s prelude to the Fifth Dimension’s The Magic Garden sparked Davis’ enthusiasm. “That record is planned, you know,” Davis said. “It’s like when I do things, it’s planned and you lead into other things. It makes sense.” He then mentioned that he had tried to get Diahann Carroll to make an album with either Webb or Shorter (!) providing the arrangements and Mel Tormé to supply the passages that would link each song. Of Bloomfield’s new band, the Electric Flag, an impossible-to-categorize aggregation blending nascent horn rock with blues, jazz and psychedelia, Davis offered: “It’s a pleasure to get a record like that, because you know they’re serious no matter what they do.” And then there’s the incredible display of Davis arguably offering more praise for Al Hirt than for Thad Jones.

Feather’s commentary around the test, published in two successive editions of the magazine in June, never states what is obvious: Davis was beginning to leave the world of jazz behind. That became clearer with the release of Miles in the Sky a month later. It included ‘Paraphernalia’ and the fruits of the quintet’s May sessions.

Three tracks were recorded between May 15 and 17, one per day. They form three chapters of a story: a summation of the quintet’s contribution to jazz, a leap into a new day, and a requiem for the soon-to-be past as well as a prologue for the soon-to-be future.

‘Black Comedy,’ written by Williams, is a crescendo of consolidation. A wild, charging obstacle course that might have left a lesser band sputtering in the dust, it’s the last straight-ahead piece the band would record. Davis and company make it count.

‘Stuff’ is less a manifesto of the shape Davis’ music would soon take and more of a carefully worded note. There’s an awkwardness to the rhythm section. On the theme statement, repeated over and over à la ‘Nefertiti,’ Williams seems a little leadfooted. Hancock and Carter, on electric piano and electric bass respectively, are also trying to get their bearings. Davis’ solo is snarky, full of variations on the theme. At about the 7:30 mark, he left fly a crazy ascent that would soon become one of his signature licks. When Shorter takes his turn, Williams begins to break free of the groove and dances around the snare. Shorter’s solo is far more discursive than Davis’, offering paragraphs of abstract funk. Hancock’s improvisation offers the best of Davis’ earthiness and Shorter’s etherealness.

‘Stuff’ is, in many ways, an anomaly in Davis’ discography. Just a month later after it was put on tape, the quintet made their final studio recordings, taping three-fifths of the lilting Filles de Kilimanjaro and by then, they were far more comfortable and conversant with an electrified sound. That being said, a close listen to ‘Stuff’ reveals that it is far more interesting than its reputation suggests.

The crown jewel of Miles in the Sky, perhaps the greatest achievement of all by the quintet, was its closer, ‘Country Son.’ It’s another recording that lurks in the background, its vision soon overshadowed by jazz-rock epics like In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew. Similar to most of the compositions on both of those records, ‘Country Son’ has no theme; a snatch of a phrase by Davis at the beginning is paraphrased during his solo that concludes the performance is the closest thing it has to a head. Instead, ‘Country Son’ is thematical, a perpetual shift from moods. There is a ballad in rubato that leads to a rock rhythm signaled by a churchy chordal pattern by Hancock that eventually dissipates back into a ballad that leads to a strut in jazz time, keyed by Williams’ syncopated beat on the ride cymbal that peters out to a final repeat of the ballad pulse.

Shorter, Hancock and Davis all play solos of dazzling complexity; by May of ’68, shifting dynamics within a single improvisation had long become old hat. But even as these three titans emerge victorious from ‘County Son’’s challenge, it’s Williams who is the composition’s ultimate hero. On the rock section of each solo, he rarely plays the main rhythm. Instead, he plays an unceasing series of labyrinthine fills that are always in time.

It is a shattering and prophetic recording. As Davis restates the tune’s opening phrase, there is a sense that a wonderful, beautiful journey has been taken. Those with keen ears will catch a brief riff that he plays at the start of his solo that would be become a primary motif of his statement on ‘Shhh / Peaceful’ from In a Silent Way.

Once Miles in the Sky hit stores, jazz-rock was on its way to becoming a movement. Davis began to draw increasing inspiration from James Brown and Sly Stone and his bands became factories populated with musicians who would make their own critical contributions to its lingua franca.

Another period of stasis was over. Miles in the Sky opened the floodgates of change.

In his autobiography Miles is dismissive of Charles Lloyd’s playing skills - he gives credit for the quartet’s success to DeJohnette and Jarrett. They were a fantastic rhythm section, to be sure, but you have to credit Lloyd for writing the songs that went on to be well received at The Fillmore and other rock venues. (I’ve always really liked Sombrero Sam on Lloyd’s Dreamweaver album.)

Great essay! As a teenager, I was buying Miles albums as they were released, along with all of the contemporary rock renaissance albums, and it was a life-defining thrill to hear all of these musics come together on my turntable. I always heard the Miles albums from ESP to Filles De Kilimanjaro as links in a chain, but nothing prepared us for Bitches Brew when it finally hit. As another early “fusion” avatar I add Joe Zawinul’s Rise And Fall Of The Third Stream to your very comprehensive list. And Miles loved to bait and aggravate Leonard Feather, so while his comments in that notorious Blindfold Test are acute and revelatory of what was to come, there’s an additional edge to them that was meant to aggravate poor Leonard.