Oscar Brown Jr. Hits the Scene

The singer-songwriter's 1960 debut album continues to thrill

Welcome music lovers and Happy New Year!

I hope that you have all had a wonderful holiday season with many chances to rest and relax, and to catch up with friends, family and on sleep too!

At the beginning of each year, I like to ease into things, kind of like a needle slowly descending onto a record, as opposed to hitting the ground running, as they say. It explains, I suppose, why I have chosen for my first essay of 2024 to revisit an album that I wrote about in the very early days of ‘Listening Sessions’: Oscar Brown Jr.’s dynamic and exciting debut album, Sin & Soul. For those interested, here is my first write-up on it from September 2021 (you may notice the extra news items included at the bottom as well—something I jettisoned soon afterwards realizing that there many other publications that would do a better job than me of keeping on top of the latest music news).

My second attempt at writing about Sin & Soul goes more in-depth and also notes something I inexplicably missed the first time around: that Robert Nemiroff, a publisher and songwriter who was married for a time to playwright Lorraine Hansberry and who was key to getting Brown Jr. signed to Columbia (Hansberry was also an important early champion of Brown Jr.) wrote the liner notes to the album. Whoops! Anyway, I hope you enjoy the essay and will share your thoughts too!

Coming up later this month will be a review of last year’s expanded reissue of Elvis Presley’s Aloha From Hawaii Via Satellite, timed to the 51st anniversary of the concert as well as a look at the early albums of Mason Williams, a jack-of-all-trades best known for the instrumental smash ‘Classical Gas’ and one of the creative forces behind The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (RIP Tom Smothers), a revolutionary television show.

Until next time, may good listening be with you all!

If you’re not yet a subscriber of ‘Listening Sessions,’ I hope you'll click the button below to subscribe and get each edition delivered straight to your inbox. I publish a long-form essay on music three times a month, every 10 days or so.

If you are a subscriber, please share ‘Listening Sessions’ with any music fans in your orbit.

Cultural currency ain’t what it used to be. In 2018, two of the late Oscar Brown Jr.’s children went on CNN to decry the devious misappropriation and dark misinterpretation of one of his most well-known songs, ‘The Snake.’ Initially recorded by him in 1963 for his final Columbia album, Tells It Like It Is!, it became a hit five years later in a souled-up version by Al Wilson. The lyrics, which are a clever recasting of the Aesop Fable The Farmer and the Viper, held a rather strange appeal to Donald Trump, who saw in them a parable to justify his anti-immigration policies even as it was a sure-fire guarantee he had no idea who Oscar Brown Jr. was or what the song actually meant. It necessitated Brown Jr.’s progeny to make clear that if the multifaceted musician was still alive, the last thing he would be is a Trump supporter.

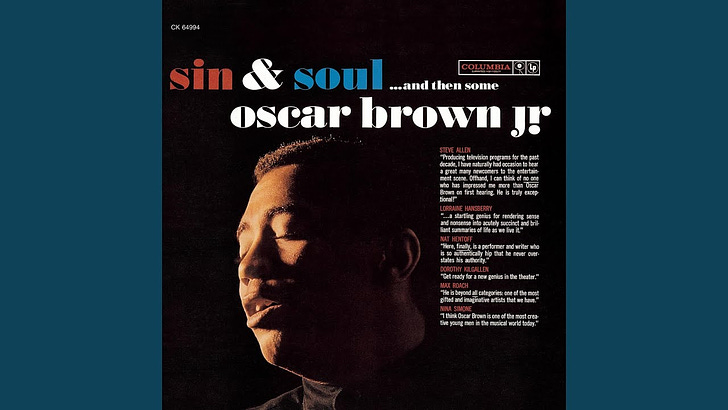

Beyond illustrating the ongoing degradation of political rhetoric, the story illuminates how Oscar Brown Jr. has become an almost invisible presence in our culture. It’s not, to be sure, an isolated example—heaven knows the concept of a common cultural framework is now largely extinct (it’s been a while since there’s been such a thing as a monoculture). But, if one glimpses the cover of Brown Jr.’s Columbia debut, Sin & Soul, released at the tail end of 1960, it does provide a striking contrast to today.

In addition to a moody photo of the singer in profile—his eyes are half closed, seemingly in the middle of a song—there are no less than six endorsements of Brown Jr. that span the panoply of the New York cultural scene at the dawn of the sixties. There’s a key inventor of late-night television (Steve Allen), a revolutionary voice in Broadway theatre (Lorraine Hansberry), one of the era’s leading jazz critics and an important figure in the alternative-press scene (Nat Hentoff), a city columnist and a panelist on one of the iconic shows from the game-show craze (Dorothy Kilgallen), a pioneer of bebop and an emerging civil-rights activist (Max Roach) and an impossible-to-categorize singer and pianist as well as an emerging civil-rights activist herself (Nina Simone).

There is a beautiful symmetry here that is the opposite of contrived. Three males and three females. Three Black people and three white people. They all sing the praises of Oscar Brown Jr. Hansberry’s blurb is particularly incisive:

“…a startling genius for rendering sense and nonsense into acutely succinct and brilliant summaries of life as we know it.”

By the time Sin & Soul hit the stores, Hansberry was a sensation. The pioneering Black female playwright’s A Raisin in the Sun would prove to be a seminal play in mid-20th century Broadway. It was at its premiere on March 11, 1959 at the Ethel Barrymore Theater that Brown Jr. met her. The 32-year-old native of Chicago had led a peripatetic existence. He had worked as a radio broadcaster, a copywriter and adman, had a stint with Uncle Sam, had been a disc jockey, dabbled for a time in PR and real estate, ran unsuccessfully as a candidate for a seat in the Illinois legislature as well as for a seat in the US House of Representatives, challenged Jim Crow-era segregation laws in the Windy City and was also a songwriter. He dedicated himself to the latter when Mahalia Jackson covered his ‘Brown Baby’ on her 1960 Columbia album, Come On Children, Let’s Sing.

Meeting Hansberry would prove to be a turning-point event that would cement his decision to focus on music, especially as her husband at the time, Robert Nemiroff, a publisher and songwriter, helped him land a contract at Columbia (Nemiroff penned the liner notes for the back cover of Sin & Soul).

The title of his debut, Sin & Soul, suggests a dichotomy even as neither word is a direct antonym of the other. It is perhaps more cogently revealed through the lyrics Brown Jr. added to ‘Dat Dere,’ one of the pianist Bobby Timmons’ most iconic lines. It starts off as a children’s song—Brown Jr. plays the part of an intensely curious and imaginative young boy as he peppers his father with all sorts of questions like “what that doing there?” and “daddy, can I have that big elephant over there?” The out chorus switches things up. Brown Jr. now assumes the role of the father. What was once playful is now philosophical. Here’s a sample:

“As life’s parade goes marching by

He’s gonna need to know some reasons why

I don’t have all the answers

But I’ll try the best I can

I’ll make him a man, that’s right.”

Not even Lambert, Hendricks & Ross—the high priests and priestess of vocalese—approached the subject matters they would extrapolate from their source material as Brown Jr. did on ‘Dat Dere.’ There is joy and delight, two emotions that Lambert, Hendricks & Ross perfected (consider, for example, the celebration of soul food that lies beneath the surface misogyny of their lyrics to Horace Silver’s ‘Home Cookin’) but a social consciousness as well. He’s not moralizing or lecturing here but, in the earnest, sincere way he sings, offering ‘Dat Dere’ as a prayer, mindful of the challenges—both personal and societal—that mark his wish urgent.

It’s that push and pull, between carrying on and getting real, that helps make Sin & Soul one of the dazzling debut records and presents Oscar Brown Jr. as a fully formed and deeply original artist.

There is a wide world that is encapsulated on the album. As Brown Jr. wrote in a short note for it, “being [Black] is not always pleasant, but is a vigorous expression for the soul.” He added, “my lyrics are verses about feelings I’ve felt and scenes I’ve dug.” These assertions are not merely hype; they are backed up conclusively.

Brown Jr. was an extraverted singer. He grabs your attention, inviting you into the milieu of each song, acting it out. In the case of ‘But I Was Cool,’ he is a stand-up comic sending up the trope of the stiff-lipped male. Each verse is a joke with the release being the punchline: an extravagantly fearless outpouring of emotion that ends with Brown Jr. asserting, against all evidence, that “I was cool.”

The cry of a street vender on ‘Watermelon Man’ is not only brought to life through Brown Jr.’s elongated phrasing but through the music which seems to reverberate around him and the band accompanying him. The song’s conceit of watermelon as an aphrodisiac strips away the racial connotations of the fruit and in its place, makes it part of a hip slice of urban life.

Brown Jr. outdoes himself on ‘Rags and Old Iron.’ Again, the lyrics and music suggest a certain type of character. Here, he is shambolic, the rickety rhythm emulating a cart laden with cast-off goods, the wheels more than a little worn and uneven, the man pulling it old and tired. He is the foil for the song’s protagonist, a heartbroken man fantasizing that the ragman will take it off his hands, rationalizing that “when love doesn’t last, then how much is it worth? / it was once my most precious possession on earth.” The only interaction between the two is when the ragman silently nods his head no at the proposition, the only things capturing his interest being “just rags and old iron.”

He assumes the role of a lush on ‘Somebody Buy Me a Drink,’ a riff on the tale of the family man who forsakes hearth and home for the bar, the brothel and a bed to hang his hat. Amidst the vivid wordplay—Brown Jr. invests his scenarios with verve and freshness, avoiding cliché and treating language as vibrant paint to electrify his canvas—he lays in a moral that the rummy offers: “now there is only one thing I feel certain of / the only true treasure in life is love / without someone to love and love you / how low you can sink.”

There is an awareness of the social context in which Sin & Soul is situated, one in which the push for equality for Black Americans was ascendant—waiting patiently for one day, in some distant future, to be accorded the same rights as white Americans turned into an insistent call for freedom now. That call formed part of the title of Max Roach’s suite, We Insist! (Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite), to which Brown Jr. contributed the lyrics. The sentiments expressed on it are fierce. They are tempered on Sin & Soul. Lines like “Brown baby, brown baby / as you grow up / I want you to drink from the plenty cup” on his recording of ‘Brown Baby’ and “I committed the crime of needin’ / crime of being hungry and poor” on his vocalese treatment of Nat Adderley’s ‘Work Song’ still, however, make clear the activist beat of Brown Jr.’s music.

‘Bid ’Em In,’ a 90-second piece of beat poetry, is all the more powerful being sandwiched between more genial fare. Brown Jr. plays a slave auctioneer, chillingly dehumanizing those he is auctioning off. By the end, his anger is palpable, one can almost see his teeth gritted as he says the final “bid ’em in,” perhaps in recognition that those listening would be both Black—the oppressed—and white—the oppresser.

That Brown Jr. follows ‘Bid ’Em In’ with ‘Signifying Monkey,’ the most elaborate flight of fancy on the album, may seem jarring but seems, to me at least, to make a crucial point that is alluded to at the end of Ossie Davis’ Purlie Victorious as Reverend Purlie observes, “I find in being Black a thing of beauty, a joy, a strength, a secret cup of gladness … accept in full the sweetness of your Blackness, not wishing to be red or white or yellow or any other race or faith but this.”

‘Signifyin’ Monkey’ is one of many songs that riffs on the figure of the trickster—’Straighten Up and Fly Right’ would be the most famous—and his interactions with an elephant and a lion. With allusions to playing the dozens and Brown Jr. singing each character as if acting, it is a joyous celebration of the indominable radiance of Black culture and its profound cross-racial appeal; Paul Robeson’s maxim that if you “get them to sing your song, … they will want to know who you are” in action.

Everyone though can relate to the feeling of working more and more to only receive less and less of the ‘Hum Drum Blues,’ a slyer, more soulful take on ‘Sixteen Tons’ (Brown Jr. would indeed cover that song in 1962) or to the mismatching of libidos underlining Brown Jr.’s lyrics to Bobby Bryant’s ‘Sleepy.’—the vocalese treatment on Sin & Soul that most matches how Lambert, Hendricks & Ross would have likely approached it. The contrast in Brown Jr.’s voice on the A and B sections of ‘Sleepy’ is especially delicious and riveting.

Equally so is how Sin & Soul closes. The broad soundscapes—among the musicians on the album are bassists George Duvivier and Joe Benjamin, pianist Bernie Leighton, drummer Osie Johnson and trumpeter Joe Wilder—narrow to just Brown Jr. and a percussionist, likely Bobby Rosengarden on conga. ‘Afro-Blue,’ a Mongo Santamaria line that John Coltrane would turn into a showpiece for soprano saxophone in 1963, is hypnotic in Brown Jr’s hands, an extolling of the authenticity of Africa as well as the dynamics of his voice. Hear how he slides upwards on a line like “two lovers are face to face / with undulating grace” and how such syllable decays on “cocoa hue.” A more fitting conclusion to the album could not be conceived. It emphasizes that the act of hearing Sin & Soul is one to be savoured and compels recall of the 11 tracks that precede it. It reiterates the immersive nature of the album. Put it on and know of Oscar Brown Jr.’s rightful and permanent place in our culture.

"Dat Dere" is a brilliant and audacious tune, and immediately got me interested in Brown. Now I know which album to get a copy of to have it.

I was just listening to "Brown Baby" today. It's amazing, and prompted me to re-read your piece on the album and Oscar Brown.

He is unusual, and able to pull off things that most singers can't (for example, Nina Simone's version of "Brown Baby" is great but feels overly theatrical by comparison).