Ray Price's Night Life and the Fork in the Country Road

Thoughts on Price's album-length evocation of the people of the night life and authenticity in country music

Welcome music lovers to another edition of ‘Listening Sessions.’

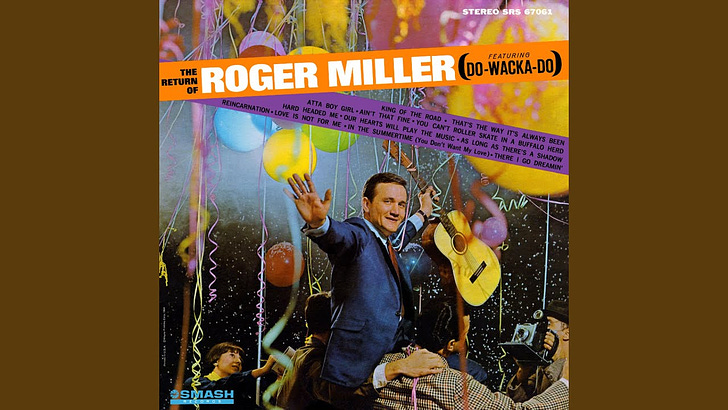

It’s been a while since I have written an essay about country music. The last one, published about nine months ago, was about Roger Miller’s two-year whirlwind as a top-40 hitmaker.

I’ve also written about Don Gibson and Marty Robbins which gives you a sense of the kind of country that I like. In the same vein, the below essay is about Ray Price; in many ways, the Frank Sinatra of country music. I focus in on his classic 1963 concept album Night Life which is a nice framework for some thoughts on the long-playing country LP and what constitutes authenticity in country music.

I hope you enjoy it.

Coming up next will be an essay on one of folk music’s greatest popularizers: Peter, Paul & Mary. I’ll hone in on the three albums they made between 1966 and 1968 on which they flirted with pop and the exploratory ethos of the time.

Until next time, may good listening be with you all!

If you’re reading this and are not yet a subscriber of ‘Listening Sessions,’ I hope you'll click the button below to subscribe and get each edition delivered straight to your inbox. I publish a long-form essay on music three times a month, every 10 days or so.

If you are a subscriber, please share ‘Listening Sessions’ with any music fans in your orbit.

Country music has, perhaps more than any other genre, been oriented around the song as opposed to the album. The individual tales that are detailed in two or three minutes usually stand out from the twelve-inch package designed to contain them. That’s not to say that there isn’t a thrill to collecting vintage country LPs. They are beautiful, living documents of a golden era when labels like Columbia, Decca, Capitol and RCA Victor were king but, to take one example, did Don Gibson, who made a fair share of classic recordings, ever make a classic album? Probably not.

Bringing up Gibson touches on another point that has often been particular to country: authenticity. His very early recordings were full of the sway of fiddles and steel guitars but once he signed with RCA, he quickly gravitated to the sweetened style of what was to be called the Nashville Sound. It fit him like a glove, particularly in its veneer of urbanity that matched his songwriting and his voice: deep, rich and suffused with the occasional moan that seemed to emanate from the deepest pits of despair. His unwavering commitment to cosmopolitan country may explain why he has often not gotten his just due. It brings to mind Waylon Jennings who, when reflecting back on his early years in the Nashville Sound mode—well tailored, well coifed and clean shaven—sang “rhinestone suits and new shiny cars / it’s been the same way for years / we need a change” and then posed the question: “are you sure Hank did it this way?” Hank, of course, is Hank Williams, Sr., the patron saint of modern country music. Of course, one may listen to today’s country radio and equally wonder “are you sure Waylon did it this way?”

Jennings’ point is well taken but even as he closed the yawning gap between the music he felt he should make and the music he was making before he went “outlaw,” it bears some degree of scrutiny. Indeed, there is almost a contrarian glee to listening to something like ‘Just Across the Way’ from his 1970 album, Waylon, and knowing that it’s darn good and it’s something that few have probably heard or remember.

It brings to mind a few years ago when I was lucky to find a sealed Willie Nelson album from 1965 on RCA. Nelson, garbed in a white T-shirt and overalls, is clean and barbered. As the clerk rang up my purchase, she stared at the album, scrutinizing the man on the cover, looking at the name of the artist, then looking at the man again and saying “I didn’t know there were two Willie Nelsons.” Puzzlement turned to celestial wonder when I told her that the Nelson on the album she was ringing up was the same as the Nelson that is part of country’s iconography.

But even those who were all duded up in Nudie had layers far darker than their attire suggested. Consider Porter Wagoner—tall, lanky, slightly goofy in appearance—who could sing a song like ‘Banks of the Ohio’ and recount to the listener, “I held a knife against her breast / as into my arms she pressed / she cried, “my love, don’t murder me / I’m not prepared for eternity”,” with such nonchalance that the effect is chilling with the realization that evil can be gussied up in flashy threads and genial “y’all come back now, ya hear” neighbourliness.

With these thoughts in mind, what is one then to make of Ray Price and more specifically, his 1963 album Night Life. It’s no stretch to call Price country music’s answer to Frank Sinatra or to crown his voice the finest to ever sing the music. It was that good. It wasn’t simply the quality of the sound of his voice—or more accurately, his instrument—or the pleasure upon hearing it or the quality of his diction—a vital consideration when Sinatra is the point of comparison—or the impeccable polish that was the signature of a Ray Price performance. It was, instead, the gap between the image of Price—cosmopolitan, urbane, someone who may circle the bars on Saturday night and remain cool and in control no matter how many libations may flow but who could also be counted on being in his usual church pew for service come Sunday morning—and what he would be singing—tales of heartbreak, woe, and other trials and tribulations of the human condition. One expects George Jones or Patsy Cline or Johnny Cash or Charley Pride to sing of suffering but when it’s Ray Price, the stakes are higher with the realization that if Price can’t catch a break, our chances at one are mighty slim.

Price, in many ways, embodied the through line that country traversed from the end of the Second World War to the start of the seventies. Initially in thrall of the western swing of Bob Wills, Price was taken under the wing of Hank Williams, Sr. in 1951, touring with him and living in his house, inheriting his backing band upon Williams, Sr.’s death and eventually forming his own band, the Cherokee Cowboys, through which soon-to-be luminaires like Nelson, Roger Miller and Johnny Paycheck passed, being among the first country artists to employ drums, perfecting a beat called the Ray Price Shuffle—a slightly syncopated, amiable gait. He then did what others—in particular, Jim Reeves and Eddy Arnold—had done by veering towards string-laden and background-singer-festooned balladry. His take on ‘Danny Boy’ from 1967 seemed to be a particular point of contention and consternation though if his critics had paid better attention, especially to his 1965 album, Burning Memories, they would have known his gravitation toward the pop side of country was already in full swing.

Two years before that brought Night Life.

“Tonight we’ve chosen some of the songs that we sing and play on our dances across the country. Songs that reflect the emotion of the people that live in the night life. Songs of happiness, sadness, heartbreak. Songs of the night life.”

- Ray Price, from the introduction to ‘Night Life,’ written by Willie Nelson, Paul Buskirk, Walter Breeland and Willie Buskirk

The LP was not the first attempt by a country artist to forge a narrative over two sides of vinyl—Marty Robbins and Johnny Cash had both already done so—but it may have been the first, save for Robbins’ Gunfighter Ballads and Other Trail Songs, to be recognized as a major album-length statement. Its reputation rests not only on its concept: a vivid twelve-song cycle of the life after dark, but also as a representation of the meeting point for the endless debate about what is and what isn’t country music.

The title track, which opens the album and initiates listeners into its world, is preceded by a short spoken introduction by Price. Notably, he refers to his live performances as “dances,” not concerts, firmly establishing a down-home, friendly atmosphere and also directly engaging with the medium—the long-playing album—in which the music he is about to perform has been packaged.

‘Night Life,’ written by Nelson, Paul Buskirk, Walter Breeland and Willie Buskirk, is a jazz song wrapped in the trappings of country. Steel guitarist Buddy Emmons, a member of Price’s backing band as well as of Nashville’s elite group of session players: the A Team, conjures lines that cut out the high end—the usual timbre of the steel guitar—and are soaked in both blues and jazz (around the time Night Life was recorded, Emmons recorded a jazz album with saxophonist Jerome Richardson, pianist Bobby Scott, bassist Art Davis and drummer Charli Persip). Price approaches his vocal like a jazz singer. He first sings the lyrics straight and than after a solo by Emmons, broadens his approach, opening his voice to draw out certain words, eliciting a cry in his phrasing. Of the night life itself, it is not its atmosphere or the action or its dissipated rhythm that is foremost, it is the inhabitants that take centre stage: the aimless, the haunted, the broken. It’s a life that just is, a sentence being served not with resignation but with acceptance. As the memorable refrain of the song goes, “the night life ain’t no life but it’s my life.”

The rest of the album fills out the dramatis personae to the title track’s mise-en-scène. The jazz of ‘Night Life’ gives way to a more straightforward country, a refined western swing with the fiddles of Shorty Lavender and Tommy Jackson providing short introductions and featured, along with Emmons, in short interludes. The mood varies from track to track to counter the somewhat static soundscape and it is not always dark.

A cover of Charlie Rich’s (another artist, like Price, who cast a worldly allure and who had a predilection for jazz) ‘Sittin’ and Thinkin’,’ is lighthearted even as its protagonist is in the clink because of his weakness for the bottle. While he pledges to his beloved that he’ll swear off the booze, he can’t promise he’ll forever remain on the wagon. Price is exquisite when singing the bridge, adding truth to the cleverness of “spent a whole lot of time / sittin’ and thinkin’ / sittin’ and just thinkin’ ’bout you / if I didn’t spend so much sittin’ and drinkin’ / we’d still be a love that we once knew.”

There are key phrases that pierce through the gloom of the night. On ‘Lonely Street,’ that durable country standard, Price lets every syllable ring out as he proclaims, questioningly, “perhaps upon that lonely street / there’s someone such as I / who came to bury broken dreams / and watch an old love die.” The dilemma at the heart of ‘Pride,’ with its radio-friendly turn from the verse to the chorus, appears irresolvable as Price cries out into the dark, “how can I leave you when I love you so / which way shall I turn, I’d sure like to know / my heart tells me stay but my pride tells me go.” The riff on the Pagliacci tale that is ‘If She Could See Me Now,’ from the pen of Hank Cochran, is a fairly devastating one. The tension between Price’s precise articulation and attack, choosing the moments to be on top of the beat and to hang off of it by a hair, and the tale he is telling is palpable. There is a lot of drama captured in a couplet like “if she could see me now, now that night life’s gone / how sad I really look without my party face on” as well as in the pathetic bravado of “I drink too much and say “who wants her anyhow?””

There is also not a lot of hope on offer. Night life here is equated with distraction, emotional wounds remaining sore, the prospects of healing dim and a cyclical kind of gloom that is sonically represented by the waltz of ‘The Twenty-Fourth Hour.’ Perhaps even on ‘Bright Lights and Blonde Haired Women,’ in which Price swears off the high life in the hopes of returning to a life of domesticity with his lover, the possibility lingers that even if she does take him back, he will soon slip back into his wayward ways. Emmons’ bright and spry steel guitar here suggests this ambivalence is mistaken but in the context of an album such as this one, remembering happy endings are in short supply is an astute position to take. And it’s not just for Price, it’s for others as well.

‘The Wild Side of Life,’ a Hank Thompson number which spawned an answer song, ‘It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels,’ (Kitty Wells’ signature song) is one of five songs which document the women of the after-hours scene. Here, the terrain tends to be a bit murkier. While the songs on the album in the first person don’t glorify the lures of wine, women and song, ‘There’s No Fool Like a Young Fool’ can seem to pack in a lot of soapbox moralizing on an album that otherwise scrupulously avoids preachiness. And while ‘A Girl in the Night’ can not conceive that the woman Price is observing couldn’t possibly be out on a night in town for a good time, it does, at the very least, recognize that the act of people watching is in many ways an act of constructing stories of the people one is observing. Perhaps then Price, in the guise of our nocturnal tour guide, is spinning a tale of woe that is simply projecting his own sorrowful story onto others.

That being said, ‘Are You Sure,’ is far more surefooted. Written by Nelson, it permits the possibility of agency and that personal growth often happens when one makes choices that are ultimately mistaken. When the decision is to partake of the party life, it does makes clear that to do so is to say yes to transactional friendships and the squandering of human potential. It is a choice to be taken only if one is, as Price asks four times, “sure this is where you want to be.” The song telegraphs the fear of losing another soul to temptation and also forms the beating heart of Night Life’s closer ‘Let Me Talk To You.’ Price saves his finest performance for here, masterfully matching the richness of Danny Dill and Don Stewart Davis’ song. Hear how he caresses the unexpected resolution of the opening line: “just one more dance / just one more chance / so I can talk to you” and centres his performance around the plea: “don’t go too far with that crowd at the bar / that is not the way to win / please fall in love with me again.” Whether his efforts pay off are left unanswered.

Perhaps unnoticed is the song’s subtle shift to the pop side of country. There’s a small string section accompanying Price as well as tic-tac guitar foreshadowing what Price’s music was morphing into. That it is essentially inobtrusive may be due to how Price has involved the listener over the course of the album, casting the net wide, creating room for those who would soon feel that he had lost his way as well as for those who found the twangier side of country too homespun, too cornpone.

Price and Night Life reminds that country is a sophisticated art form, as American as jazz and at its best when focused on our collective stories, both good and bad. If a country song does that, it ultimately doesn’t really matter how the music sounds. It’s about as authentic as music gets.

As I dive deeper into Country, I realize that there are hidden doors that I didn't know existed. I know Price pretty well and so appreciate your deeper analysis. I'm glad that when i first heard For the Good times back when it was a hit, that I listened intently and didn't turn the dial!

Some of my earliest memories are of a radio on top of the refrigerator and my mother dancing around the kitchen to the songs of Ray Price. She especially liked “Make the World Go Away”, and to this day when I hear it I remember the young woman she once was. Thanks again for you perspective.