The Everly Brothers' Late-Sixties Reinvention

After the hits ended, Don and Phil Everly continued to make interesting music

Welcome music lovers to a new edition of ‘Listening Sessions.’

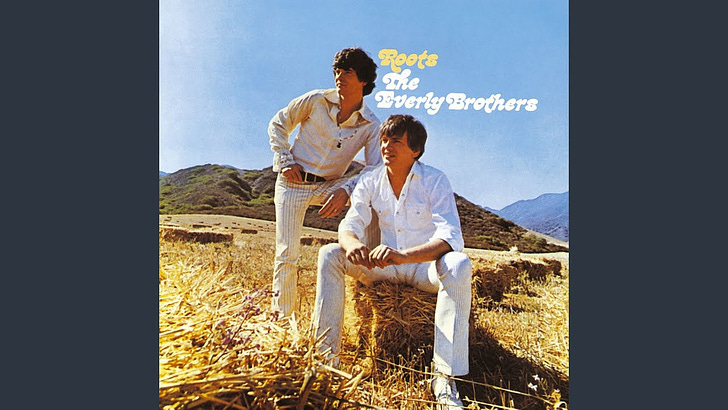

This time around, I'm exploring the music that the Everly Brothers recorded in 1967 and 1968. During that time, they released their final Top 40 hit, the wonderful ‘Bowling Green,’ and three albums, including their masterwork, Roots. In the early days of my Substack, I wrote about Roots in the days after the news of Don Everly’s passing.

The below essay also includes some thoughts about Roots. Not everything Don and Phil recorded during the late sixties works but there is enough that is either great or good to say that it was an artistically fertile time for them. I hope you enjoy the essay and that you share your thoughts as well.

‘Listening Sessions’ remains on a modified publishing schedule until the end of this month. The next time I will be in touch will be on April 16 with a review of two new archival jazz recordings: Alice Coltrane’s The Carnegie Hall Concert, which was released a few weeks ago and Yusef Lateef’s Atlantis Lullaby: The Avignon Concert, which is coming out on Record Store Day (April 20).

Until next time, may good listening be with you all!

If you’re not yet a subscriber of ‘Listening Sessions,’ I hope you'll click the button below to subscribe and get each edition delivered straight to your inbox. I publish a long-form essay on music three times a month, every 10 days or so.

If you are a subscriber, please share ‘Listening Sessions’ with any music fans in your orbit.

In 1967, the Everly Brothers scored their first Billboard Top 40 single since the beat-a-go-go ‘Gone, Gone, Gone’ hit #31 in 1964. When ‘Bowling Green’ sneaked in at #40 on July 8, 1967, it would be the last time Don and Phil would have what could be called a hit.

‘Bowling Green’ is a paean to Kentucky, a state that looms large in the Everly story. Father Ike was born in Muhlenberg as was Don. Mother Margaret was born in Rockport. Phil, on the other hand, was born in Chicago. When Don and Phil appeared on the Christmas 1970 episode of The Johnny Cash Show with Ike, they chose to sing another song about the Bluegrass State. The song, ‘Kentucky,’ written by Karl Davis and first recorded by Don and Phil on the sparse Songs Our Daddy Taught Us in 1958 also closed Roots, recorded ten years later.

Both albums are pinnacles of the Everly Brothers on LP. The former is a hymn to the ethereal blend of Don on the lower harmony and Phil alighting on top. The latter, with its airchecks from when the whole family had a radio show, has an almost hallucinogenic vibe, an album-length ode to where Don and Phil had come from and where they were going. It concluded two years of records which, save for ‘Bowling Green,’ were commercially negligible but undeniably fascinating artistically.

By then, Warner Bros. Records, which also included Reprise Records, was a hotbed of the esoteric strand of rock and pop music. There was the twee baroque of Harper’s Bizarre, the cinematic and kaleidoscopic Van Dyke Parks, the scatological the Fugs, the arresting and thoroughly unique Beau Brummels and the askew view of Randy Newman not to mention the dense psychedelia of the Grateful Dead.

In their way, the Everly Brothers built Warner Bros. Records. The label was two years old and very much in the middle of the road where they were lured away from Cadence Records in 1960. The contract was lucrative—said to be the first one valued at over $1,000,000. They came out of the gate strong, building on the string of hits that made them one of the hottest rock and roll acts and in the process, certifying Warner Bros. as a major label. Things, though, quickly began to fracture for Don and Phil.

Their third album for Warner Bros., Both Sides of an Evening, included such inexplicable selections as ‘Mention My Name in Sheboygan’ and ‘My Mammy’ alongside gems like a balls-to-the-wall version of ‘Muskrat’ and an elegant take of the standard ‘Don’t Blame Me,’ with a gorgeous lead by guitarist Hank Garland. Soon after, a protracted dispute with Wesley Rose of Acuff-Rose Music prevented them from continuing to write their own songs or recording any by the firm’s staple of songwriters, include Felice and Boudleaux Bryant, who wrote a substantial number of Don and Phil’s most memorable hits.

That precipitated a series of albums comprised of covers. Some of the music was of interest. There was the rhythmic two-step of ‘Silver Threads and Golden Needles’ from 1963’s The Everly Brothers Sing the Great Country Hits, a motoring ‘Dancing in the Street’ from 1965’s Rock’n Soul and a sensitive ‘People Get Ready’ from Beat & Soul from the same year. Others were more curious—the Everly Brothers becoming a weird hybrid of an oldies act with arrangements and a sound that were more contemporary.

There was also a stint in the Marines and both brothers dealt with substance abuse. And yet as the British Invasion hit with a bang in 1964, the Everly Brothers, whose commercial prospects had already significantly receded by then, seem to have been validated by the clear stylistic connection that Don and Phil’s music had with the Beatles, the Hollies, and Peter & Gordon; the Rolling Stones too even if it is hard to directly place it in the music they made in the mid sixties.

Original material dominated 1966’s In Our Image and Two Yanks in England along with the beat-driven sound that became dominant for the Everlys by this time. It all sounded, as it always did with Don and Phil, interesting. Yet, even the presence of much of the Hollies on the latter album, it failed to mitigate the impression that the Everly Brothers continued to sound like they were marking time. The next two years would prove more fruitful.

The Hit Sound of the Everly Brothers, released in February 1967, may seem like a regression. After all, most of it is dedicated to what Don and Phil had been doing earlier in the decade: recording cover versions (only two of the album’s 12 songs were originals). To their credit however, almost all of them were significant reworks of the source material such as the modernist edge and Bo Diddley beat added to Hank Snow’s ‘I’m Movin’ On.’

‘Blueberry Hill,’ which leads off the album, slowed down the New Orleans gait that defined Fats Domino’s iconic interpretation. A trombone obbligato and solo add other unique touches. But what makes this version of ‘Blueberry Hill’ so intriguing is how it teases out a new approach to the Everly Brothers’ singing. There is an underlying introversion to their voices as they sing the song. Don and Phil lean back here, riding subtly underneath as opposed to right on top of the musicians accompanying them (here it’s the players who would retrospectively be known as the Wrecking Crew). It’s an approach that is also present on their cover of Burt Bacharach and Hal David’s ‘Trains and Boats and Planes’ and Don Gibson’s ‘A Legend in My Time,’ as well as on one of the album’s two originals, ‘She Never Smiles Anymore,’ one of the very first recordings of a song written by Jim Webb.

There is also the Everly Brothers’ first dalliance with psychedelia. It pops up in the processed background vocals on Ray Charles’ ‘Sticks and Stones’ and even more so on a foreboding version of ‘House of the Rising Sun.’

The album prophesizes new directions that Don and Phil could take. ‘Bowling Green,’ their return to the Top 40, suggested another.

With a flute and oboe baroque introduction and judicious use of the woodwinds throughout the rest of the song, credited to bassist Terry Staler and Jacqueline Ertel, Phil’s then-wife, ‘Bowling Green’ nods to the late sixties. There is a male chorus and a folk-rock lead-guitar part. The Everly Brothers fall right in, extolling of “way down in Bowling Green / the prettiest girls I’ve ever seen” and of “Kentucky sunshine [that] makes the heart unfold / it warms the body and I know it touches the soul.” The underlining theme of it all may be, at least to these ears, the indominable ethos of Don and Phil—a nostalgia meeting up with the present day. It may well be one of their most heroic recordings.

It led off The Everly Brothers Sing where it is an anomaly. The subtle beauty of ‘Bowling Green’ is swiftly subsumed by a production in which the drums pound, the guitar fuzzes to the point of suffocation and the brass bleat as loud and harsh as the perpetually unwelcome morning radio alarm. The severe leaning into bombast was an unfortunate decision for the ideas embodied in some of the songs are interesting.

‘I Don’t Want to Love You’ and ‘Deliver Me’ are both exercises in the kind of vampy, hooky pop that had swiftly thrust Neil Diamond into the spotlight. The former has a murky, slightly outré interlude into the bridge and the latter meshes those signature Diamond handclaps with the blue-eyed soul of the Righteous Brothers. If the energy level had been dialed back just a bit, they may have been the kind of deep cuts that the Everly Brothers’ connoisseur could break out to demonstrate their bona fides.

But it’s not just the productions, it’s also Don and Phil, or mostly Don really, who are often shouting the lyrics—compare the almost-extreme verses of their cover of ‘Mercy, Mercy, Mercy’ with the better balanced and soulful chorus.

Some of the album reaches that kind of Zen. There’s the inclusion of arguably the best track from both In Our Image and Two Yanks in England: ‘It’s All Over’ and ‘Somebody Help Me’ respectively but to cite those is almost cheating. Better to focus, if one is able to look past the carnival-like opening and far-too-literal conceit at play, on something like ‘Mary Jane’ where one sees again a future for Don and Phil continuing to crystalize. ‘Talking to the Flowers,’ their most overt attempt to capture what would be the legend of the Summer of Love, is a marvel in its relative restraint and how the Everly Brothers manage to sell the lyrics while also capturing a sense of dislocation: two singers synonymous of sock hops and milkshakes trying to find a place in a world that had traded that innocence for a far more potent kind.

There is something fascinating about hearing records like these. The stars of yesteryear who tried to get with the changing times (a requirement that has long since passed in music and the culture at large) may not have always done so in a completely convincing manner but often did with enough conviction to make the final result much more than a mere curiosity. Rick Nelson, Del Shannon, and Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons all did so. The Everly Brothers did too. The results got better once they teamed up a rising producer at Warner Bros., Lenny Waronker.

Prior to hooking with Waronker, Don and Phil’s follow-up singles to ‘Bowling Green’: ‘Love of the Common People,’ produced by Dick Glasser, who helmed both of their 1967 LPs, and ‘Milk Train,’ produced by Wes Farrell, both telegraphed the direction that Waronker would take their music. Both build on ‘Bowling Green’’s fusion of the old and the new. They are nods to the nostalgia of the rugged American spirit countered with cosmopolitan soundscapes. They are first drafts of Roots, released in late 1968.

It’s this album on which the argument that the late sixties were a fertile era for the Everly Brothers principally lies. Waronker further dials back the bombast with a clearer and more atmospheric production. It’s the ethereal bed of sound that he applied to albums like the Beau Brummels’ Triangle, Van Dyke Parks’ Song Cycle and Randy Newman’s debut. Roots is oriented in the past—both the Everlys’ and America’s. It’s notable that Don and Phil, when turning their attention to where they came from, they move past their halcyon days of the late fifties and early sixties to stop at their youth—the days of the Everlys as a family group. Equally, the one time Don and Phil do turn to their early years as hitmakers, it is to offer a radically reworked version of ‘I Wonder If I Care as Much,’ which first appeared as the B-side of the big bang of ‘Bye Bye Love.’ The country-folk of their earlier version is swept away in the haze of a fuzz guitar and the two-step beat is replaced by one that is only implied. Instead of pouring their hearts out, the Everly Brothers sing the lyrics with fragility, the harmony brittle, their voices quiet. It’s one of the album’s many profound moments.

It’s preceded by an alternative rollicking and genteel interpretation of the old Jimmie Rodgers’ standard ‘T for Texas.’ There’s also the calliope-heavy ‘You Done Me Wrong,’ the boot-boogie of ‘Shady Grove’ and a cover of Glen Campbell’s modern spiritual ‘Less of Me’ that peels the varnish away from Don and Phil’s harmonic blend. Where they belted things out in 1967; in 1968, they stepped back as they did on ‘Blueberry Hill.’ It’s there even as they attack the beat on Merle Haggard’s ‘Mama Tried.’ The harmony retains an edge, a cool moodiness.

Roots has long been regarded as one of the first statements of country-rock, formalizing the merger of the two genres that had been present ever since the birth of rock and roll in the mid fifties. That reputation is well deserved. Roots, though, is deeper than that in its layering onto the album of the work of several of the artists that Waronker was producing.

Randy Newman contributed ‘Illinois,’ which leads off the album’s second side. He also plays piano on it. The song is relatively straightforward, both in structure and content, by Newman’s standards but it’s sophistication and the way the recording floats as a genre all of its own makes it superb. Don and Phil mesh well with Newman.

Co-arranging with Don and Phil was Ron Elliott of the Beau Brummels whose Bradley’s Barn has a similar feel to Roots. By then, the group was just Elliott and lead singer Sal Valentino. As a songwriter, Elliott had a preternatural ability to avoid cliché and standard song forms. Each Elliott song was an adventure, full of imagery often from science-fiction or fantasy, that when they were sung by Valentino, one of the most distinctive and unsung voices of the sixties, they often attained a level of sui generis.

Elliott contributed two songs to Roots. ‘Turn Around,’ initially recorded for Bradley’s Barn and leading off that album, tells of a summer relationship between the “barefoot boy” and the “barefoot girl.” Don and Phil’s softened vocals heighten the song’s poignancy, especially in the suspension at the end of a line like “turn around, the summer’s almost over / turn around, the summer’s almost gone.”

‘Ventura Boulevard,’ Elliott’s other contribution, covers the same ground but in a more poignant way. Over a bed of sweeping strings arranged by Nick DeCaro, the Everly Brothers let the words tell the tale. The second verse hits hard: “It was a hay ride, a gay ride or more / I can’t remember the time / it was a slow walk, a fast talk for sure / we had an ice cream for only a dime / we had the good time, she wanted.” If there is a better song that captures the particular melancholy of time passing that the end of summer can bring up, I haven’t heard it.

Don and Phil are similar hushed on Roots’ apex, a slow, mournful version of Haggard’s ‘Sing Me Back Home’ that zeroes in on the pain in which a death-row prisoner proceeding to meet his end wishes not only to hear a song of home, but through its singing, to be transported there, the soul leaving the body about to be drained of life. It’s another of the indisputably great recordings by the Everly Brothers that reveal their artistic renaissance in the late sixties.

When ‘Sing Me Back Home’ ends, the album's concluding montage begins. It consists of a benediction by Ike Everly from the old family radio show, a reprise of ‘Shady Grove’ and a snippet of ‘Kentucky.’

Everything that Don and Phil released in 1967 and 1968 has been collected by Cherry Red Records on Down in the Bottom: The Country Rock Sessions 1966-1968, notwithstanding that only a fraction of the music on the collection could properly be called country rock. It includes a nice set of rarities. Gems include a slow walk through Neil Young’s ‘Mr. Soul,’ the Elliott-penned ‘Empty Boxes’ (the B-side of ‘It’s My Way’) and a very spacey version of ‘Love With Your Heart.’ All together, the music tells a tale, maybe the most interesting one of the music of the Everly Brothers.

If you’re not yet a subscriber of ‘Listening Sessions,’ I hope you'll click the button below to subscribe and get each edition delivered straight to your inbox. I publish a long-form essay on music three times a month, every 10 days or so.

Fine piece and tribute to the Everly Brothers. I wonder how many duos owe their harmonizing inspiration to them.

Best Harmony of all time, always be my favorite duo,first album I ever bought,was the everly, brothers