The Lovers, the Dreamers & Bobby Scott

A look at a great unsung singer, pianist, composer, songwriter and arranger

Welcome music lovers to a new edition of ‘Listening Sessions,’ and an especially warm welcome to those who have newly subscribed to my Substack.

Today’s edition is a deep dive into the genius of Bobby Scott, among the most talent and gifted musicians of his generation yet all but forgotten today. The opportunity to listen to a lot of his music over the past week while writing the below essay has been a joy and I hope it inspires you to get acquainted with Scott’s music, if it’s new to you, or to rediscover it, if you haven’t heard it in a long while.

If you’re reading this and are not yet a subscriber of ‘Listening Sessions,’ be sure to click the button below to subscribe and get each edition delivered straight to your inbox. I publish a long-form essay on music three times a month, every 10 days or so.

If you are a subscriber, I hope you'll consider sharing ‘Listening Sessions’ with any music fans in your orbit.

Bobby Scott is an artist that most know even if the name draws a complete blank. It’s two songs that have granted Scott a measure of anonymous ubiquity: ‘He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother,’ which Scott co-wrote with Bob Gordon and ‘A Taste of Honey,’ which Scott co-wrote with Ric Morrow.

Scott was many things besides a songwriter. Born in 1937 in Mount Pleasant, New York, he was of the class of artists for which easy categorization fails beyond the fact that he was a child prodigy. He commenced formal musical training before he hit double digits, became a working musician before turning a teenager and performed with such luminaries as Louis Prima and Gene Krupa as well as scored a record contract before reaching adulthood. Primarily a pianist, Scott could also play vibraphone, accordion, clarinet, cello and bass. He was well-versed in jazz, pop and soul. In addition to being a songwriter and composer, he was an expert arranger. Bobby Scott was also a jazz and pop singer and a supremely fine one at that.

The era in which Scott got his start—the fifties into the sixties—was rich in singers that turned the interpretation of popular song into high art. Scott’s gifts encompassed all the tools of the singing trade. A tone that was rich and well-rounded, resonant and welcoming to the listener. Phrasing that brought a logic and consideration to each line of a song. Dynamic control that further aided his ability to communicate as a singer. Timing that was natural and fitting of his chops as a jazz pianist. He often brought a sense of swagger that suggested it was hard-earned, substantial dues have been paid in the quest for a life well-lived, and the need to pay even more possibly linger around the corner.

In a time in which pop and jazz singers were legion, Scott stood apart, not just because the depths of his vocal gifts but also that they were only a fraction of his musicianship and of his desire to discover and give expression to them all. An industry that thrives on various forms of narrowcasting, even back in the fifties and sixties but far less encompassing, suffocating and tyrannical than today, almost always consigns artists like Scott to the margins and indeed, to study Scott’s discography is to quickly become acquainted with his itinerant history. There were stints on Bethlehem, ABC-Paramount, Verve, Atlantic, Mercury, Columbia and Warner Bros. between 1954 and 1970, a top-twenty novelty hit ‘Chain Gang’ in 1956 and albums that alternated featuring Scott as pianist, singer, arranger and composer—all work that has been spottily, if at all, reissued on CD. Spotify is also a muddle, offering a variety of legitimate and not-so-legitimate versions of his records. Journalist and blogger Marc Myers offers some well-needed and authoritative guidance to discovering the joys of Bobby Scott (read here, here and here). In my years of record collecting, I’ve managed to score a few of Scott’s LPs and they provide a useful entry into his work, especially as a singer.

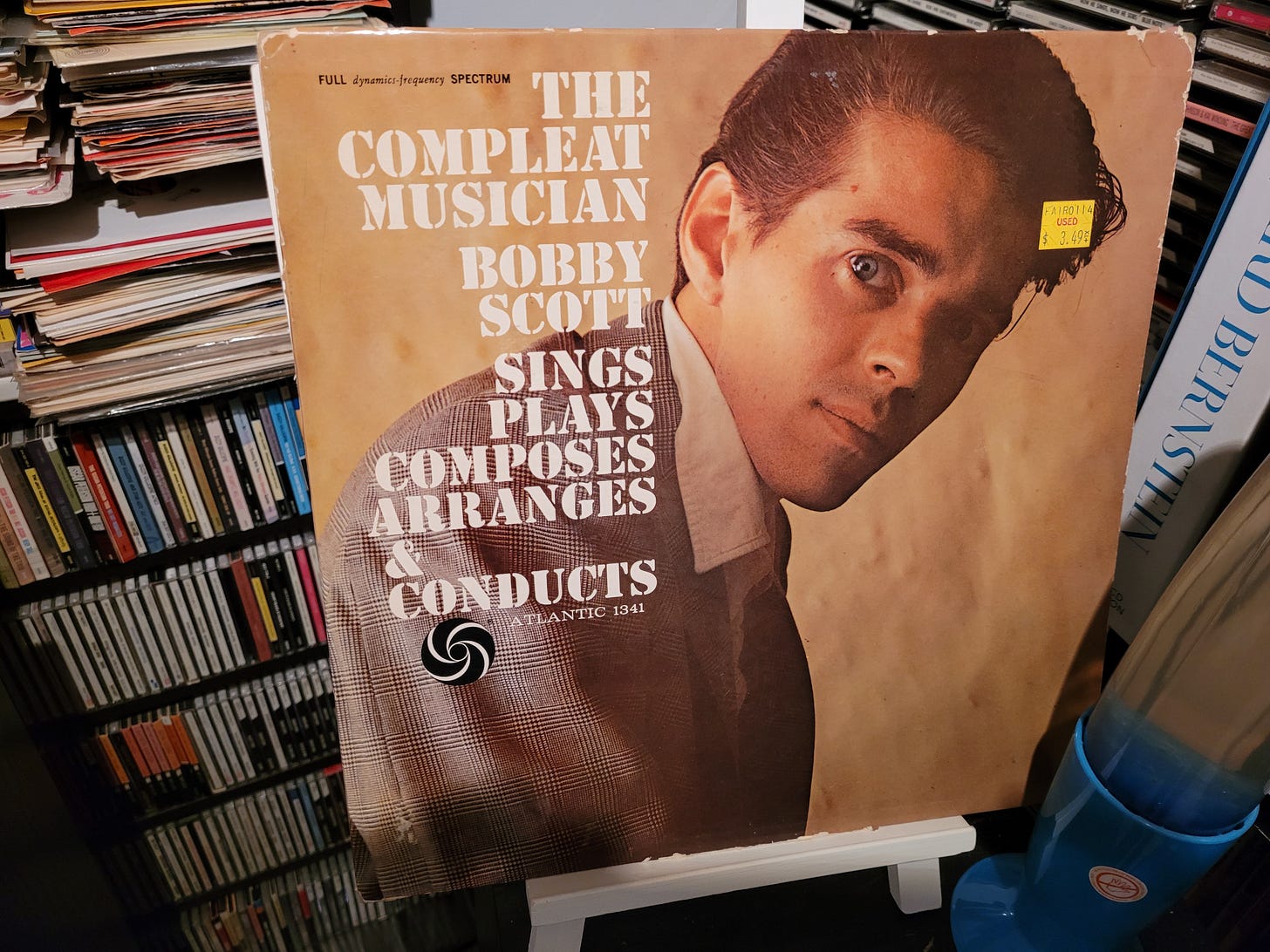

The Compleat Bobby Scott, released on Atlantic in 1961 when Scott was 24, was an attempt to encapsulate the widest possible breadth of his artistry. The cover of the album references the many caps that Scott wore in its making: in addition to singing, he’s the piano player, the composer of two of the songs (‘The Prison Yard’ and ‘Ironside Train’), the orchestral arranger as well as the conductor of them. He also put together a deeply compelling program of standards, both relatively familiar (‘The Trolley Song’ and ‘Without a Song’ for two examples) and others still awaiting wider discovery (‘Roses in the Rain’ and ‘It Happens Each Spring’ anyone). There are ballads, up-tempo swingers, blue-eyed soul and intimate pieces with just Scott and his piano. It all confirms that he was a singer of often exquisite and arresting taste. He had a way of sighing on a note like Chet Baker but more resolutely. Tonally, there are traces of Bobby Darin, Jack Jones and Steve Lawrence but with significantly advanced jazz chops. In truth, to hear Scott’s singing voice is a delight, but focus too much on the sheer perfection of his sound and you’ll miss his way of building a performance, such as the song-length climb that defines his approach on a sublime rendition of ‘Way Down Yonder in New Orleans’ or how he soars over the climax of ‘The Trolley Song.’

His touch on a ballad can be impossibly tender, mastering the intimacy inherent to masters like Sinatra, Bennett and the granddaddy of them all, Crosby, turning ‘How Are Things in Glocca Morra’ into a one-on-one dialogue with the listener—hear how he alights on the closing “this fine day.” Contrast that with the supremely soulful ‘The Prison Yard’ in which Scott wordlessly moans and wails away on the piano, barrel-house style.

It’s that piano sound, reminiscent of late-night honky tonks or a saloon in a Wild West theme park, that rings through on many of the sessions that Scott played on for Quincy Jones in the sixties as well as on ‘In and Out,’ a highlight from guitarist Wes Montgomery’s 1964 album Movin’ Wes, Montgomery's first recording for Verve and the beginning of his move away from jazz in favour of what may be called a highly cultured and literate form of easy listening.

In 1967, Scott was signed to Columbia Records and he recorded a sophisticated album of pop music called My Heart in My Hands. Here, the emphasis is on Scott the singer (if that point was in doubt, give a gander at the cover in which “the singing” is italicized before Bobby Scott). He also wrote eight of the 10 arrangements. The overall sound and feel is not unlike the string of classic and near-classic albums Tony Bennett recorded in the mid-sixties—that frequent Bennett collaborator Torrie Zito supplied two arrangements and was the album’s primary conductor makes that connection explicit.

If there was a song that holds the key to the album, it may well be ‘Eight Million Stories (in the Naked City),’ an expert meditation that in a crowded metropolis, individual dramas swirl all around. People on the up, an equal number on the down; as Scott sings, “all of them schemers.” There’s a sheen of cultivated urbanity that abounds: Scott’s smooth delivery, launched with the first smoky line delivered on the opener ‘It’s Crazy,’ one of the two songs that Scott co-wrote on the album, is a worthy foil to the fully realized, suave arrangements creating a sound that is both heart and head, sentimental and streetwise.

It comes through on a bright rendition of ‘The Days of Wines and Roses,’ the elegant life lesson of ‘One is a Lonely Number’ (the other song from Scott’s pen) and the closing ‘Smile,’ which he sings as an exhortation and washes away any temptation towards the maudlin. A delicate ‘If Ever I Would Leave You’ is another highlight. Scott sings the words as if they are unfolding in the very moment.

There are few among Scott’s peers that are his equal but here, as before, the music, of the highest caliber, had minimal impact, as did his follow-up on the label, Star, which was more soulful in flavour, yet room was made for the bright and bouncy ‘Paris Is at Her Best In May,’ a vivid travelogue number in sparkling technicolour.

Opportunities for Scott to record became fewer and farther between in the seventies and eighties. A date for an indie label in New Jersey, MusicMatters, released in 1990, For Sentimental Reasons, had Scott singing and playing piano with a small group for a relaxed set of standards. The recording is frequently stunning. Scott’s voice, weathered a bit by age, is still rich and profoundly expressive. The tone remains impossibly smooth, especially on a very memorable ‘That Sunday, That Summer’ as well as ‘Mamselle.’ A sequel, Softly, was soon recorded. It was fated to be Scott’s last album. On it, Scott’s voice has shrunk but is still gloriously listenable, his phrasing not unlike that of tenor saxophonist Ben Webster’s way on a ballad: economical, often ending in a long breath of air, the loss of dynacism making manifest the impact of the lung cancer that would take Scott’s life at the age of 53 on November 5, 1990 in New York.

Yet, the album is not a premature requiem, but an expression of the humanity that Scott brought to music making. The beautiful simplicity of Scott’s rendition of the Muppet classic ‘The Rainbow Connection’ is a moving reminder that his ability to transmit beauty was not an affectation but a window into his heart and soul where in both resided a sensistive and generous artist.

Postscript: While, as noted in my essay, most of Bobby Scott’s recordings are almost impossible to find, I am pleased to share that the five albums highlighted here are available for streaming on whichever service you prefer.

Thank you for this article. I've always thought A Taste of Honey was one of the most evocative ballads ever written. It incites a mood of instant or near instant "recognition" in the listener that he knows that song, from somewhere, although he may never have heard it before, which most truly sublime popular songs seem to have. Musically, it reminds me of the persuasively authentic yet inauthentic American folk songs which Dmitri Tiomkin wrote in the late 50s. John Lennon hated that The Beatles recorded it, but when was Lennon ever not Lennon?

I'm looking forward to discovering this man as a singer.

People whose work I'd enjoy reading about:

1. Neal Hefti

2. Bernice Petkere

3. Louis Jordan

4. Georgie Fame

This is a terrific Substack you're doing. I'm always glad to see a new one.

I'm one of those that knew the songs but not the name behind them. Thanks as always for a fantastic deep dive into a forgotten corner of the music world!