Sin & Soul, Starring Oscar Brown Jr.

Reflections on one of the truly great debut albums plus Roberta Flack, Art Blakey & the Jazz Messengers and the new Rolling Stone 500 Best Songs of All Time list

Oscar Brown Jr. was a singer, songwriter, playwright, poet, author, performer, Civil Rights activist, television host, political candidate and serviceman, to name but a few of the hats he wore throughout his life.

He also recorded one of the most dazzling debut records that has ever been released, 1960’s Sin & Soul on Columbia Records. It remains a startling and refreshing listen.

There is an enduring mystique about the debut album, that first opportunity accorded an artist or band to put forth a musical vision and engrave it onto wax. Some hint at the sonic revolution to come—Bob Dylan’s first immediately comes to mind—while others make clear that the revolution has arrived fully formed—think the Band’s Music from Big Pink. Others use those first moments of the first song like a jolt of lightning—think of Paul McCartney’s count-off to start ‘I Saw Her Standing There’ on the Beatles’ Please, Please Me or the truly disturbing monologue at the beginning of ‘(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Below, We’re All Going to Go’ that kicks off Curtis Mayfield’s solo debut.

Sin & Soul starts with a single crack on the snare before Brown Jr. sings about “breaking rocks out here on the chain gang” to begin ‘Work Song,’ a jazz line written by cornetist Nat Adderley and one of the signature pieces of Cannonball Adderley’s band for which Brown Jr. added lyrics.

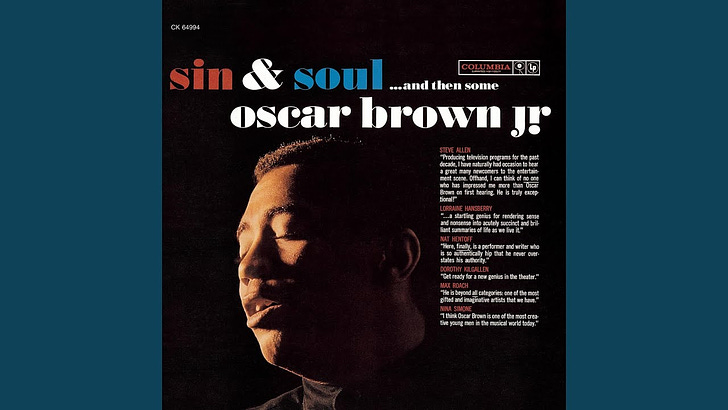

Before we get too deep into the music, let’s take a look at the album cover. Brown Jr. is photographed on the left, head turned about 45 degrees, most of the right side of his face obscured in a shadow, eyes half closed, presumably in the act of bringing one of his songs to life. To help drive home the point that the music we are about to hear is by an artist that is esteemed by his peers and worthy of our attention is a series of six endorsements spanning a wide cross-section of the entertainment and media world circa 1960. We have late-night television (Steve Allen), Broadway theatre (Lorraine Hansberry), jazz and music criticism (Nat Hentoff), journalism and the game-show craze (Dorothy Kilgallen) and musical peers (Max Roach and Nina Simone). Three males and three females. Three Black people and three white people. Members of the establishment and others pushing society forward from its edges. In other words, Oscar Brown Jr. is for one and for all. He is for me. And for you too.

In Hansberry’s blurb, the pioneering playwright states that Brown Jr. has “a startling genius for rendering sense and nonsense into acutely succinct and brilliant summaries of life as we live it.”

Likely more than anyone else, it was Hansberry that gave Brown Jr. his break. He met her at the premiere of her landmark play, A Raisin in the Sun, and she connected him with her husband at the time, the publisher and songwriter Robert Nemiroff, who was able to secure Brown Jr. a record contract with Columbia.

Her quote on the cover of Sin & Soul provides a key to the album’s enduring power. Its 12 songs are snapshots of life both serious and lighthearted (sometimes both at the same time) acted out by Brown Jr. The idea of singing as a form of acting was up until Sin & Soul perhaps best exemplified by Harry Belafonte, who used his training as an actor to inform his performances of folk songs, work songs, spirituals, calypsos and ballads and give them a veneer of powerful authenticity. As the legendary Paul Robeson once said to Belafonte, “get them to sing your song and they’ll want to know who you are.”

Brown Jr. achieves that through the sheer versatility of his voice—an instrument of almost inexhaustible expressive power that he employs to brilliant effect on Sin & Soul.

Take, for example, ‘Rags and Old Iron,’ which opens the second side. A tale of heartbreak over lost love, Brown Jr. is a recently jilted fellow who hears the back-alley echoes of a ragman whose cries are evocatively created by Brown Jr. at the beginning of the song and returned to throughout. He sings of yearning for the ragman to buy his broken heart but in a cruel twist of fate, after relaying his tale to him, the ragman simply nods a wordless no and continues on his way. Brown Jr.’s singing here is intimate—it’s direct, unadorned—you feel as if he is talking to you, and only you.

His lyrics to ‘Dat Dere,’ one of jazz pianist Bobby Timmons’ most famous compositions, first recorded while he was with Cannonball Adderley’s group, is another prime of example of how Brown Jr. acts through singing. A song about a young boy asking his father a series of inquisitive questions, Brown Jr. makes the startling choice of setting the song’s out chorus to a meditation on parenthood: the role of the parent to do his or her best to equip the child for adulthood, and the anxieties associated with that task. He marks this transition through his voice: almost scat-like during the verses, intoning solemnly with a hint of vibrato during the out chorus. A clinic in singing and songwriting.

On Sin & Soul, Brown Jr. indulges in stand-up comedy (the hilarious ‘But I Was Cool’), the hippest Aesop Fable you’ll ever hear (the swinging, infectious ‘Signifyin’ Monkey’) and also introduces us to the characters that make up the neighbourhood (the aforementioned ragman in ‘Rags and Old Iron,’ the street calling ‘Watermelon Man,’ the wino in ‘Buy Me a Drink’ and the couple with bedroom issues in ‘Sleepy’). In each, he inhabits the milieu conjured by his lyrics, acting out roles and inviting us into his world of lively characters but also one in which racism is a fact of life.

While he was recording Sin & Soul, Brown Jr. was collaborating with jazz drummer Max Roach on the urgent We Insist! Freedom Now Suite, a key artistic work in the movement for Civil Rights. The messages of the suite are ever-present in Brown Jr.’s debut. As ‘Work Song’ grooves along, his lyrics remind us that while the song’s protagonist, a prisoner on a chain gang, did rob a supermarket and left the grocer (mortally?) wounded, his hunger and destitution, the result of a society whose very structure is based on depriving Black men like him full participation in it, left him with no choice but to do what he did. ‘Hum Drum Blues,’ a breezy lament of the futility of getting ahead, can also be understood through this lens.

‘Brown Baby,’ a lullaby expressing the hope and the optimism that the younger generation will reap the rewards of the struggles and sacrifices of those preceding them is Brown Jr. at his most tender—hear how close he sings into the microphone. It was also the first of his songs to be recorded by another artist when the great Mahalia Jackson included it on her album, Come On Children, Let’s Sing.

Brown Jr. dramatizes a slave auction in ‘Bid ’Em In’—90 seconds of slam poetry that lays bare the dehumanization of selling a human body. While he plays the role of the auctioneer, his anger and fury at what he is telling is ever present. He doesn’t shy away from hiding his disgust. His final “Bid ’Em In” makes that crystal clear.

The first 11 songs of Sin & Soul take us on a journey full of characters, places, commentaries on life. It is only fitting that the album concludes with a final benediction, just Brown Jr. and a percussionist playing ‘Afro-Blue,’ a Mongo Santamaria composition with lyrics by the singer. It dares us to “dream of a land my soul is from”—the most obvious allusion here is to Africa—and proceeds to paint a picture of a boy and girl dancing that may or may not be a dream which slowly fades away into the night. The album is now complete and we have an opportunity to take in all that we have heard and reflect on the genius of Oscar Brown Jr., an extraordinary singer, songwriter and storyteller, and an album that is one of the most finest debut records of them all. It deserves your complete attention.

BONUS TRACKS

A present for Roberta Flack fans: Earlier this month, seemingly out of the blue (I only became aware after seeing this tweet), expanded versions of Roberta Flack’s Chapter Two and Quiet Fire, released in 1970 and 1971 respectively, were posted to streaming sites. Chapter Two adds a grooving version of Joni Mitchell’s rare ‘Midnight Cowboy’ (written for John Schlesinger’s movie but not used) while Quiet Fire is augmented with seven bonus tracks, including a startling reworking of Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Goin’ On’ set to the rhythm of ‘Go Up Moses,’ which opens the record, a 15-minute version of ‘Superstar’ (made famous by the Carpenters) which features the irrepressible groove of Bernard Purdie’s drums and a profoundly intimate rendition of the Beatles’ ‘Here, There and Everywhere.’

The original albums are uniformly excellent, highlighting Flack’s rare ability to bring depth and meaning through her slow, deeply considered interpretations of songs like Bob Dylan’s ‘Just Like a Woman,’ Carole King and Gerry Goffin’s ‘Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow’ and ‘The Impossible Dream’ from Man of La Mancha as well as exercises in groove like the aforementioned ‘Go Down Moses.’ On both, she is joined by some of the best musicians at the time specializing in soul, jazz and funk, including Purdie, bassists Chuck Rainey and Ron Carter as well as guitarist Eric Gale. Eugene McDaniels and Donny Hathaway are also all over both records. Collectively, it makes for essential listening wherever you stream your music. No word yet on whether this music will get a physical release. Fingers crossed!

Art Blakey in Japan, 1961: As I have mentioned in more than one previous post, we are in a golden era of jazz archeology in which newly unearthed performances by the music’s legends are being found and released at a furious pace. Just this past week, Blue Note Records announced that a previously unreleased live recording by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messenger from Japan in January 1961 will be coming out on November 5 on two LPs or two CDs in a deluxe package that will include, among other things, a new interview with Wayne Shorter.

Featuring one of Blakey’s finest aggregations of the Jazz Messengers: Shorter on tenor, Lee Morgan on trumpet, Bobby Timmons on piano and Jymie Merritt on bass, this looks like another winner (no surprise that Zev Feldman is involved here as usual!), especially the prospect of a 22-plus minute version of Charlie Parker’s ‘Now Is the Time.’

To whet our appetite, an extended version of Timmons’ iconic ‘Moanin’’ has been released—dig how Blakey eggs Merritt on during his bass solo.

Rolling Stone updates its 500 Best Songs of All Time list: Earlier this month, Rolling Stone unveiled a new version of its 500 Best Songs list, 17 years after it released its initial tabulation. To begin to dissect the list or quibble with where a certain song landed or bemoan those songs that made the cut the first time around but didn’t on the new list is a fool’s errand best left to others. In my casual perusal of the list, I think the new version is an admirable endeavour. It casts a wide net that refuses to favour the music that has long reigned on lists of this type (i.e. music created roughly between 1955 and 1975) and recognizes that the music of today should be evaluated alongside music of long-ago yesterdays, even as I am far more familiar with the latter than the former and cognizant that it’s only through the passage of time that we can fully determine the merits of a piece of music.

That being said, the list only barely scratches the surface of jazz, the Great American Songbook or music outside of the First World not to mention the English language, and ignores symphonic music entirely. Imagine if a publication or even someone like Ted Gioia dared to compile a best-song or best-albums list that attempts to encompass music in its entirety, attempting to compare, for example, the Beatles with Beethoven. Perhaps another fool’s errand, but noble enough to at least make an attempt.

And just a bit of personal news: I’ve been immensely gratified by the response I’ve received to my essay on Elvis Presley’s early-60s recordings in Nashville (if you haven’t had a chance to read it, check it out here). I am also pleased to share that it’s been picked up on two fan sites dedicated to Elvis: Elvis Day by Day and Elvis Australia.