Frankie Laine & Anita O'Day: Escapades in the Art of the Singer

Highlighting two superb LP explorations of popular song

Welcome music lovers to another edition of ‘Listening Sessions’!

One of the topics I keep coming back to is the golden era of pop singing during the fifties and the sixties. It was a glorious time bursting with superb interpreters of the Great American Songbook and lovingly crafted long-playing albums of their interpretations of that glorious canon of popular song. Among her contemporaries, Anita O’Day was one of the most committed to the purity of jazz and Frankie Laine was one of the singers whose work in novelty songs obscured his bona fides as a serious interpreter of song. The below essay celebrates them both by highlighting one album by each. I hope you enjoy it and will share your thoughts as well.

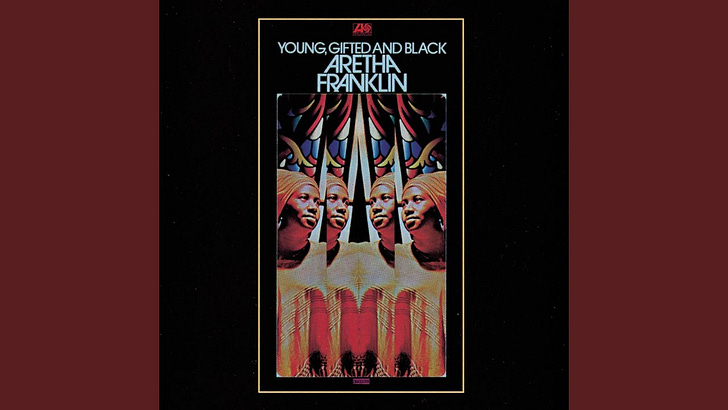

The last time I was in touch was earlier this month with an essay on Aretha Franklin. Some of you may not have received it due to an email delivery problem (not sure what exactly the issue was but am hoping for some more information from Substack). In case you did not receive it, here it is below.

Until next time, may good listening be with you all!

If you’re not yet a subscriber of ‘Listening Sessions,’ I hope you'll click the button below to subscribe and get each edition delivered straight to your inbox. I publish a long-form essay on music three times a month, every 10 days or so.

If you are a subscriber, please share ‘Listening Sessions’ with any music fans in your orbit.

That Frankie Laine’s biggest claim to fame was as a deeply extraverted Western balladeer is part of the curious way that reputations were made during the golden era of the pop singer. The drama he imparted, for example, to the themes of John Sturges’ Gunfight at the O.K. Corral or the long-running series Rawhide may be thrilling to some while being, to others, another damning piece of evidence from the irredeemably cornball fifties.

Indeed, novelty was pervasive then and many singers were caught up in its undertow: Patti Page (‘(How Much is) That Doggie in the Window?’), Doris Day (‘Whatever Will Be, Will Be (Que Sera Sera)’), Kay Starr (‘Wheel of Fortune’), Rosemary Clooney (‘Mambo Italiano’) and Perry Como (‘Hot Diggity (Dog Ziggity Boom)’) were all much more interesting singers than their calling cards would lead to believe. Frankie Laine most certainly so too.

A glance at his biography reveals a singer of deep breadth who was conversant in music of all types. His influences foretell the fluidity that would distinguish Laine among his contemporaries. Enrico Caruso, Bessie Smith, Gene Austin, Jimmy Rushing, Bing Crosby, Nat Cole and so on and so forth. He could knock you out with exuberance in excelsis (his “move ’em on, head ’em up / head ’em up, move ’em on / move ’em on, head ’em up / Rawhide!” is perhaps, save for its launching of Clint Eastwood’s career, the sole remaining hold that Rawhide has on the public consciousness). He could excavate the pathos out of something like ‘That Lucky Old Sun’ without entirely succumbing to mawkishness. His bolero rendition of ‘Jezebel,’ recorded in 1951, seems like a message beamed in from the future for in it, there are echoes of the revolution of rockabilly, the vocal tricks of Roy Hamilton and Elvis Presley, and the ultra-emotionalism of early Tony Bennett, Johnnie Ray, Gene Pitney and Cilla Black.

A Laine vocal could often be rich, both in the precision of his delivery with each syllable explicitly articulated, and his bending and stretching of notes that added his personal touch to a song’s melody. He had technique to spare and I suppose that is why an adjective like grating may not be far from mind when listening to him at full blistering bravado. But that can obscure Laine’s gifts when he was singing for the LP as opposed to the 45 rpm single market.

On two ten-inch albums he recorded on Columbia in the early fifties with Paul Weston (another music maker who is fairly unknown today), Laine tempers the tricks to allow the singer to take the foreground and the technique to recede into the background. Particularly on 1954’s Mr. Rhythm, Laine glides easily through ‘Lullaby of Rhythm,’ first recorded by Benny Goodman in 1939, while hitting the beat snuggly on top. On ‘My Ohio Home,’ with its shift to a two-step, toe-tapping rhythm halfway through, Laine is an ideal deliverer of the song’s message of nostalgia for one’s hometown. The ballad ‘Judy’ has Laine use the cry in his voice to emphasize the whole-hearted sincerity at the heart of a Frankie Laine performance.

At a time when the twelve-inch long-playing pop album became an art form—a collection of music to edify one’s home and its occupants—Laine is rarely cited as one of its more astute practitioners. Yet, lurking in the shadows is Jazz Spectacular, recorded on an autumn’s night in 1955, squeezed in between sets during an appearance by Laine at the Latin Quarter in New York. A collaboration between Laine and trumpeter Buck Clayton, it’s less of an unlikely pairing than it seems. Laine did spend much of his early days trying to make a name for himself (he was then known under his given name, Frank LoVocchio, before changing it to Frankie Laine in 1938 when he was 25) as a jazz singer. Instead of its surface incongruousness, what makes Jazz Spectacular a miraculous recording is the uncompromising nature of its concept.

Unlike almost all other albums of the time that paired a singer with a jazz small group—here, the group is a bit larger at 10 musicians—Laine is another member of the band, mostly allotted a chorus (or two at most) with the players under Clayton’s leadership soloing at length. It’s an all-star group. There’s Budd Johnson on tenor saxophone, Sir Charles Thompson on piano and a bevy of trombonists: Dickie Wells, Urbie Green, J.J. Johnson and Kai Winding.

If Laine gets a bit too carried away at times—on the opening ‘S’posin’,’ he seems almost desperate to prove himself worthy of such an extravagant caper as this—when he gets in the pocket, look out! On a slinky interpretation of Bobby Troup’s ‘Baby, Baby All the Time,’ Laine is languid, reeling the listener in to hang on each word and each of its syllables. The closing ‘Rose of Picary’ is absolutely riotous. And yet, it’s sadly missing in action on streaming services. Jazz Spectacular is the kind of hidden gem that is just screaming for a reissue.

Another album in which Laine’s artistry is in full effect is 1958's Torchin’, a collection of saloon songs that is just as unknown though, happily, it is available on streaming services. It’s the kind of collection perfect for this time of year: autumn is here and with it, days for reflection amid the emerging cold and the background of nature putting on its annual show of auburn and burnt orange.

The primary charm of Torchin’, in addition to its well-balanced program of standards, is Laine, who essays performances of deep worldliness. Like all great ballad singers, he places his trust in the material and lets it guide him. The arrangements by Frank Comstock, best known for scoring the Rocky and Bullwinkle series, are mostly unobtrusive. Torchin’ is Laine’s show all the way.

That material doesn’t get much better than Johnny Green and Edward Heyman’s ‘I Cover the Waterfront.’ Laine’s hits the opening verse, among the most poetic ever written, out of the park. Hear the subtle rise as he sings, “in the still and the chill of the night.” The chorus has Laine’s emotively embellishing the song title—just enough to exemplify his jazz-like phrasing. The repeat of the B section, with just the strings and piano, digs into the desolation that is the song’s beating heart and in the last A section, Laine finally gives in to anguish before ending on as quiet a note as he began. The shifting dynamics of quiet to loud and back again in Laine’s masterful interpretation is a template returned to frequently on Torchin’.

‘Here Lies Love,’ which Bing Crosby first made a hit, has the same undulating spirit and an even more profound performance from Laine, eliciting dramatic effect through its absence, sliding in moments of propulsion on the B section as well as a drop into the lower register just when it's needed. The effect of it all—intoxicating is what it is—is such that by the next song, ‘You’ve Changed,’ the listener is swept along the tableux that Laine is weaving.

It is another knockout performance full of the generosity and warmth that, more than anything else, was Laine’s calling card. There’s also a bravura and epic ‘These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You)’ and a victorious ‘Body and Soul,’ a musical Waterloo, if ever there was one, for any jazz musician and/or the jazz singer.

Torchin’’s peppier moments are also well taken. Comstock’s light, verging on easy listening, chart for Hoagy Carmichael’s ‘I Get Along Without You Very Well’ (the serendipitous moment of Laine singing Carmichael’s ‘Rockin’ Chair’ at a Los Angeles club in 1946 with the songwriter in attendance—Laine had no idea—led to Carmichael being his first major benefactor and Laine getting signed to Mercury Records) is just right for Laine’s bittersweet approach. ‘Midnight on a Rainy Monday,’ with echoes of raindrops in the orchestral introduction, gets close to the sound of the records he was making for the singles market. Here, though, it’s a winner with Laine setting the scene of “no jazz, no laughs, no crowd” evocatively.

Two songs that Laine co-wrote: the title track, written specifically for the album and ‘It Only Happens Once,’ penned during the years he was trying to make it, serve as thematic bookends, giving Torchin’ a structure that mirrors Frank Sinatra’s saloon-album triumphs with Nelson Riddle and Gordon Jenkins. It is persuasive evidence that Laine was a serious singer.

Anita O’Day, on the other hand, has never required such a clarification or defence. Her bona fides as a jazz singer were always beyond question. She got her start singing during the height of the Great Depression at brutal contests of endurance and sleep deprivation called walkathons. Couples competed to keep walking long beyond what was humane. Depending on the rules, times for rest were provided yet many couples, who didn’t want to quit, had to keep going with one sleeping on his or her feet with the other holding on to the slumbering partner while plodding along. Walkathons could last for months and spectators could buy tickets to take in the morbid spectacle. Laine also worked the walkathon circuit and sometimes appeared alongside a teenaged O’Day.

One of the great examples of O’Day prowess was her eight-minute feature in the groundbreaking documentary on the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival: Jazz on a Summer’s Day. She starts ‘Sweet Georgia Brown’ slow and smoldering and edges into a seduction that ends on an elegant—O’Day is white-gloved and wears a hat with feather trimming at the front—yet insouciant note. ‘Tea for Two’ is supersonic. On both, O’Day dances near and around the melody, poking at the corners, recomposing on the fly, treating the mic as a dance partner. She has the aura of Barbara Stanwyck at her most commanding, daring anyone, for even a moment, to take their eyes or ears away from her.

The comparison to Stanwyck is not entirely coincidental. In Howard Hawks’ Ball of Fire, Stanwyck appears as the singer for Gene Krupa’s band and while it’s Martha Tilton that is dubbing for Stanwyck on ‘Drum Boogie,’ it was O’Day who was on the bandstand with Krupa when the movie was released in theatres at the end of 1941.

O’Day was a tough customer. An excerpt from her autobiography, High Times Hard Times, from Reading Jazz, a collection of writings compiled and edited by Robert Gottlieb, recounts in unflinching detail how she got hooked on heroin in the early fifties and the lengths that she and drummer John Poole, who worked with the singer for 40 years or so, took to score and to avoid hard time.

At that time, O’Day was at the start of a very fruitful association with Verve Records, recording a series of intimidatingly good albums, such as All the Sad Young Men, released in 1962 near the end of her time at the label. It’s a musical marriage of cool: O’Day’s is often detached and unsentimental but affecting nonetheless and arranger Gary McFarland’s is often pointed and wistful. The band assembled is heavyweight: soloists include Herb Pomeroy on trumpet, Bob Brookmeyer and Willie Dennis on trombone, and reedmen Phil Woods, Walter Levinsky, Zoot Sims and Jerome Richardson. The rhythm section is comprised of Barry Galbraith on guitar, Hank Jones on piano, George Duvivier on bass and Roy Haynes on drums.

The opening ‘Boogie Blues’—a takeoff on the aforementioned ‘Drum Boogie’ and initially recorded during O’Day’s time with the Krupa band—is icy and hip; the musical equivalent of an arched eyebrow. McFarland’s chart is full of trumpet blasts and serpentine, swaggering saxophone lines that update the big-band sound for the ultra-modern sixties. O’Day hangs behind the beat and Haynes adds a pop to it. ‘Boogie Blues’’ aloofness has charm. It’s an ambience that is one of the two moods that feature throughout All the Sad Young Men.

A similar feel pervades the urbane ‘One More Mile.’ McFarland’s writing here is staccato, providing a brassy countermelody to O’Day’s easy vocal before solos by Jones and Pomeroy. ‘Up State’ sheds the reserve after the crime-show-like introduction for a quick blues chorus by O’Day before she trades eights then fours then twos—the singer scats—with Dennis. It’s a tossed off trifle of exuberant jazz. The closing cover of Horace Silver’s ‘Senor Blues’ goes back to laissez-faire up-tempo.

The rest of the album is reserved for ballads. O’Day is not necessarily the first choice that may come to mind when thinking about ballads but on All the Sad Young Men, they are its heart. ‘You Came a Long Way from St. Louis’ is not typically taken at as slow a pace as O’Day and McFarland do it here but their interpretation is an exercise in devastating irony. O’Day sizes up the returning Missourian wise guy, a man who “climbed the ladder of success” and “broke a lot of hearts in between” and declares that there is little wise about him. McFarland’s voicings are harmonically rich, much like those of his primary influence, Gil Evans.

He scores ‘I Like to Sing a Song,’ which he co-wrote with Margo Guryan, deep in her jazz-songwriting phase, primarily for clarinets. The main line has a longing to it, redolent of autumn leaves at their most iridescent. It’s a beautiful and special arrangement, entirely fit for O’Day’s voice, full of wisdom hard won. There’s also a noir-ish quality to it; if she was not a femme fatale, then she was certainly one who knew the cost of loving the wrong kind of man. That’s the portrait she paints on ‘A Woman Alone With the Blues.’ McFarland uses the brass to cushion O’Day on the start of each A section. As Haynes lays down a shuffling beat for its conclusion, a flute line adds a bittersweet hue. Woods solos on clarinet, another sonic pastel of a winning performance. As it ends, O’Day scats—the song’s heroine is unbowed.

The album’s title is derived from the majestic song by Fran Landesman and Tommy Wolf, ‘Ballad of the Sad Young Men’—a complex and difficult meditation on loneliness. It’s challenging because of the poetry of the lyrics. They require the loving care of a singer and the attention of the listener from beginning to end (start perking your ears up in the middle and the song’s impact is entirely lost). McFarland’s arrangement is impressionistic—hear the brass chorale after the opening verse, another of the evocative examples of what is now a lost art form. If the rest of the performance doesn’t live up to its first gorgeous moments, no matter, especially as a wry version of Ellington’s ‘Do Nothin’ ’Till You Hear From Me’ is up next, full of the disarming charm of Anita O’Day.

Select All the Sad Young Men as the chaser to Laine’s Torchin’ and you got two escapades in the timeless art of the singer. Enjoy.

This was a fantastic essay and I appreciate the introduction to Frankie Laine. Looking forward to spending the day with Torchin tomorrow. You’re right about it being great autumn music!!

Thanks for highlighting these underappreciated singers! I should say, though, that 'Roses of Picardy' is on Spotify.